JUPITERIMAGES/AFPLast September, during the week in which Brazilians celebrated their independence, an important international journal carried some worrisome news for the country in its online version: Brazil has one of the highest rates of the occurrence of a chronic disease that affects 300 million people worldwide and every year kills 250,000: asthma. One in seven adult Brazilians – 12% of the population over 18 has already been medically diagnosed as suffering from asthma and last year one in every four (24%) were breathing with a distressing wheeze, the most characteristic sign of the disease. The condition is marked by a narrowing of the airways, coughing and a shortage of breath that worsens at night, according to an analysis of the respiratory health of 308,000 people from 64 countries conducted by researchers from the University of Massachusetts, from the Public Health School at Harvard and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in the United States, based on an inquiry by the World Health Organization.

JUPITERIMAGES/AFPLast September, during the week in which Brazilians celebrated their independence, an important international journal carried some worrisome news for the country in its online version: Brazil has one of the highest rates of the occurrence of a chronic disease that affects 300 million people worldwide and every year kills 250,000: asthma. One in seven adult Brazilians – 12% of the population over 18 has already been medically diagnosed as suffering from asthma and last year one in every four (24%) were breathing with a distressing wheeze, the most characteristic sign of the disease. The condition is marked by a narrowing of the airways, coughing and a shortage of breath that worsens at night, according to an analysis of the respiratory health of 308,000 people from 64 countries conducted by researchers from the University of Massachusetts, from the Public Health School at Harvard and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in the United States, based on an inquiry by the World Health Organization.

Published on September 9 in the European Respiratory Journal, these data place Brazil in sixth place in the proportion of confirmed cases of asthma in adults, behind Norway, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Sweden and Australia. What is worse is that it ranks first concerning suspected cases, many of them possibly unidentified because of people’s inadequate access to health services. These rates are similar to those found in another broad survey concluded just recently, the International Study of Asthma and Allergy in Childhood (Isaac), which in its third phase assessed 300,000 children and adolescents from 55 countries. Isaac was carried out with the participation of researchers from São Paulo, Curitiba, Porto Alegre, Recife and Salvador and detected symptoms of asthma in 16% to 29% of 6 and 7-year old Brazilian children and in 12% to 31% of 13 and 14-year old adolescents.

These numbers prove that asthma, once more frequent in economically developed nations, has grown in Brazil over the last few decades. And not just here, where it is estimated that, between children and adults, there are 26 million people with asthma and that it is the cause of death of 1 out of every 700 Brazilians – a rate 10 times higher than that of some developed countries. In fact, asthma cases are rising in several western countries, especially in Latin America, where health resources are normally scarcer.

From many points of view, asthma has turned into a huge public health challenge. The observation of a different occurrence pattern from the one known until recently, for example, has been making experts from all over the world reassess their concepts about environmental factors associated with the rise in the illness. The higher frequency in countries with extreme socio-economic conditions – it is more common in richer countries, where it seems to have leveled off, and in the poorest countries, where it is growing – shows that the so-called hygiene hypothesis, fashionable until recently, does not explain a lot. Proposed in 1989 by the English epidemiologist David Strachan and explored over the succeeding years by the German allergist Erika von Mutius, this idea suggests that exposure to infection by microorganisms (or the toxins produced by them) in infancy makes the defense system more prone to unleash reactions that inhibit the development of allergies. Thus, an immune system influenced by these environmental factors would have weaker signs of asthma, the origin of which, it was believed, was predominantly allergic until twenty or thirty years ago. According to this hypothesis, it would be advisable to leave children exposed to less aseptic environments.

The hygiene hypothesis explains in part what happens in rich and industrialized countries, where towns are cleaner, water and sewage are treated and, in theory, there is better access to the health network. However, it also makes growing ratios of asthma in parts of the world where a considerable proportion of the people live packed together in largely unhealthy environments, like slums, inexplicable.

This is precisely why the way proposed in 2000 by the pediatrician Eugene Weinberg, from the University of Cape Town in South Africa, as an explanation of the current expansion patterns of the illness has grabbed the attention of researchers from the area. Weinberg observed that the risk of developing asthma was greater in towns than in rural areas of African countries and he put forward the hypothesis that it is not just a disease associated with development, but also – and perhaps mainly – with urbanization. Migration from the countryside and villages to fast-growing urban centers exposes people to other types of agents that cause infections and allergies, to air pollution and to a greater level of psychological stress. Asthma is also associated with changes in diet and the level of physical activity. Other studies carried out in Africa and Asia favor this idea, although the specific factors that increase the risk of asthma in these situations are unknown. The hypothesis may help when it comes to understanding what happens in many towns and cities in Latin America, suggest researchers Alvaro Cruz and Maurício Barreto, both from the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), in an article published this year in the journal Allergy in partnership with Phillip Cooper, from London University, and Laura Rodrigues, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

“If, in fact, the issue of hygiene has a major influence on the development of asthma, it is likely that just a small proportion of Brazilian children from low income backgrounds have this allergic type of asthma,” comments Cruz, a professor of pulmonology at UFBA, where he is investigating the socioeconomic benefits of treating serious asthma. “At the same time, this observation strengthens the idea that lack of hygiene increases the risk of non-allergic asthma appearing.”

Although one cannot discard the idea that people are becoming increasingly allergic, experts are certain that allergy is only part of the problem. At most, it explains half the cases. The other half are like a type of sphinx, clamoring for the enigma to be deciphered, a task to which, in fact, Brazilian researchers have been dedicating themselves tooth and claw.

REPRODUCTION FANCEY.CA/FACESMarcel Proust: castigated by crises of breathlessness throughout his lifeREPRODUCTION FANCEY.CA/FACES

Inflammation

One of the weapons used in this attack is the bronchoscope, a device for the observation of the airways of living people that also allows small tissue samples to be collected. As a result, our understanding of the origins of asthma and its treatment has started changing. Researchers found that in asthma sufferers the bronchi and bronchioles, branches of ever-narrower channels that carry the air from the trachea to the lungs, were constantly inflamed. This discovery changed once and for all the notion that had persisted for more than half a century that asthma was caused by a temporary allergy, which was why it was only fought in the crises with medication that relaxes the muscles of the bronchi – bronchodilators, or little pumps – and large doses of hormonal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, administered either orally or intravenously.

In this approach to treating asthma as inflammation, the teams of pathologists Thais Mauad, Marisa Dolhnikoff and Paulo Saldiva, from the Medical School of the University of São Paulo (USP) have been investigating for the last 10 years what is wrong with the airways of people who have serious asthma. Analyzing the respiratory apparatus of people who have suffocated to death from asthma, they found significant alterations in the structure of the bronchi and bronchioles. In the innermost layers of the wall of these ducts, the elastic fibers were broken, they revealed in 1999 in an article in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. There was also an abnormal proliferation of this type of fiber in the deepest layers, possibly as the result of an incomplete repair process. These alterations are part of the so-called remodeling of the airways and, when added to other transformations, left the walls of the bronchi 50% thicker than normal, thus reducing the space for air to pass through.

“These alterations explain why breathing becomes so difficult during an asthma crisis,” says Thais. In the respiratory system, these fibers function like springs. They stretch when people breathe in and then return spontaneously to their normal length, thereby expelling air from the lungs. With the fibers broken, less air leaves. Thais also saw that the lungs of people who had died from asthma were damaged at the point where bronchioles attach to the alveoli, microscopic pockets within which gas exchange occurs – the oxygen from inhaled air goes into the blood, which in turn releases the carbon dioxide to be eliminated.

Associated with the remodeling is an intense inflammatory reaction that increases the production of mucus. Marisa and Thais discovered that this inflammation greater than previously imagined: it affects the entire respiratory system – and not just the main airways ducts – from nasal mucus to the conjunctive tissue of the lungs, where researchers found the greatest transformations. According to the authors, in an article from May of this year in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, there is an excessive build-up of collagen in the pulmonary tissue that helps to make the airways rigid. “Over the long-term, inflammation may lead to the production of growth factors and alter the structure of the lungs,” Thais suspects.

The material from the São Paulo tissue bank, however, did not enable researchers to reach a conclusive result. The alterations seen in the tissue extracted in the 73 autopsies may result from the fatal crisis and not from the different stages of evolution of the disease. When alive, most of these people did not control their asthma properly. Only 34% were being medically monitored on an on-going basis and only 12% were being treated with inhalable corticosteroids.

In a partnership with researchers from Canada and Australia, Thais took part in work that evaluated samples from six tissue banks, using material taken from people suffering from asthma in varying degrees of seriousness. Coordinated by the pulmonologist Alan James, from the University of Western Australia, and published in March in the European Respiratory Journal, this study revealed that the intensity of damage – in particular, the increase in the thickness of the layer of muscle fibers – is related to the seriousness of the asthma, but not to its duration. The result indicates that remodeling of the airways occurs in the early stages of asthma and determines its severity. In other words, the thicker the smooth muscle, the more serious the asthma.

Andrew Bush, from the Imperial College School of Medicine, in London, is trying to complete this picture. He carried out a series of studies with tissue samples taken from the airways of children and saw that the alterations in the walls of the bronchi may be present as early as three years of age – and regardless of the occurrence of inflammation. These data suggest that asthma may establish itself very early on and impose a long-lasting limitation on respiratory capacity. “This means that the critical window for preventing asthma from developing, by trying, for example, to avoid children getting viral infections, might be very short – just three years,” says Thais.

VISUALS UNLIMITED/CORBIS/CORBIS (DC)/LATINSTOCKSick tree: inflammation reduces the passage of air in the respiratory ductsVISUALS UNLIMITED/CORBIS/CORBIS (DC)/LATINSTOCK

Treatment

“The idea that significant inflammation was behind asthma was not novel,” explains the pulmonologist José Roberto Lapa e Silva, from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ). In the late nineteenth century, when the French writer Marcel Proust, the author of the classic novel, A la recherche du temps perdu [In search of lost time] began to suffer the dramatic asthma crises that would dog him for the rest of his life, pathologists had already observed signs of serious inflammation in the airways of people who had died from asthma. However, only more recently has the conclusion that the inflammation is not only serious but also long-lasting driven the experts to rethink its treatment.

The bronchodilators, used only in crises, have been replaced by others that are used continuously and have a prolonged action. Instead of high doses of oral or injectable anti-inflammatory drugs, doctors have started prescribing extensive therapies, using low doses of inhalable corticosteroids. Administered in this way, corticosteroids act on the airways and are destroyed by the liver before spreading through the organism, thereby reducing any undesirable side effects.

This strategy has proved effective in controlling 90% to 95% of asthma cases, generally those that are either not serious or only moderately serious, with sporadic crises of breathing difficulties that do not go as far as making it impossible to enjoy a viable working or social life. The challenge is to understand what happens with the rest of the cases – and how to treat them. These are people with the so-called serious or difficult to control asthma, against which bronchodilators and inhalable corticosteroids are almost innocuous and do not avoid the often daily crises in which the imperceptible act of filling the lungs with air and emptying them becomes as arduous as breathing with the head covered with a plastic bag.

“This group of asthmatics is the one that suffers the most and that costs the most for the health system,” says Thais. Data from the Ministry of Health indicate that, every year, asthma causes 350,000 admissions to public hospitals, each one consuming hundreds to thousands of reals – a study carried out in Spain by Joan Serra-Batlles in the 1990’s showed that spending on hospital admissions represented a third of the annual expenditure of asthmatics with consultations, exams and medication. These are resources that could find better use. They could, for example, help with the creation of specialist asthma teams in the public health network and with supplying drugs considered standard in the treatment of the disease, as provided for in the National Asthma Plan, which is still in its introductory phase in Brazil.

The problem is that there are no end of doubts about the disease and the most suitable approaches to treating the many forms of serious asthma that exist. Bush’s results, for example, created more uncertainty than explanations about the evolution of the illness. In a review of the theme published in 2008, he states that it is improbable that the alterations in the walls of the airways are triggered by the inflammation – if they were, they would have the role of repairing the damage they caused . He also raises two other possibilities. Perhaps the inflammation and the remodeling are independent phenomena; or, maybe the remodeling is the consequence of a disturbance in the tissue repair mechanism. These doubts, which result in part from difficulty in monitoring the evolution of asthma in humans, are not the only ones. It is not known, for example, whether the serious form is a progression from the light or moderate forms, or whether the clinical signs correspond to the damage that pathologists see in the tissue.

Faced with so many questions, experts from Brazil and abroad are trying to develop a more accurate definition of what is understood by serious asthma and how best to reduce its signs efficiently – in the last 50 years, asthma, known since Ancient Egypt, has already received a dozen or so definitions. In the opinion of Alberto Cukier, a pulmonologist from the USP Heart Institute (InCor), the current classification is simplistic because it brings together under one name variations of a condition that, despite similar clinical signs, may have resulted from different biochemical and physiological mechanisms. Pulmonologists call these variations in serious asthma phenotypes; they are clinical manifestations that result from the interaction between the environment and the genetic constitution of the individual. In some cases, these phenotypes may even represent different illnesses.

“Classifying the different manifestations of asthma just by their level of seriousness is possibly not the best way of defining the most suitable treatment for each of them,” says Cukier. “However, for the time being, classification by phenotypes is an idea that only works from the didactic point of view.”

Perhaps not for long. In 2010, the Year of the Lung, the most important communities of experts in the world – the European Respiratory Society and the American Thoracic Society – are likely to propose new guidelines for classifying and treating serious asthma, taking phenotypes into account. “These guidelines should benefit the patients, because they can avoid using medication that doesn’t work for certain types of asthma,” comments the pulmonologist Rafael Stelmach, from InCor. “So it will become possible to reduce unwanted side-effects.”

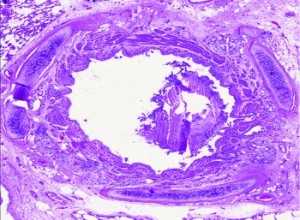

PATHOLOGY DEPARTMENT/FMUSPAlmost blocked: transversal cut of the bronchus of an asthmatic personPATHOLOGY DEPARTMENT/FMUSP

Phenotypes

The construction of phenotypes takes into account at least three characteristics: the presence (or not) of allergy, the age when the crises started, and recent hospitalization. “This is important information because it allows us to reorient treatment,” says Stelmach. Some examples help one to understand this. The asthma of someone who is allergic to mites or dust (atopic asthma) normally responds well to treatment with corticosteroids, while non-allergic asthma (non-atopic) demands higher doses of these drugs or different medication. Shortage of breath crises are generally stronger when asthma appears after childhood – and more mild when it starts before the age of 12.

Over the last few years, Cukier and Stelmach have been tracking 54 patients with serious asthma, in order to identify factors that help control the disease better. These are people who have been living with the disease for 30 years, on average, and suffer frequent crises, to the point of being unable to work, walk or even calmly take their meals. Two out of three have an allergy. A similar proportion also suffers from rhinitis, gastro-esophageal reflux, anxiety or depression. One in three had been hospitalized in the year prior to the survey and half had already been placed in intensive care at least once in their life because of asthma.

The researchers treated these people for 12 weeks with long duration bronchodilators and inhalable and orally administered corticosteroids. Stelmach and Cukier hoped to be able to control the asthma of two thirds of them. Nevertheless, at the end of the therapy, only one third no longer suffered from the daily crises. The researchers are trying to explain what happened, but preliminary analysis indicates that some of them people did not take the medication as they should have done.

Failing to adhere to treatment, in fact, is a common problem in Brazil, where only 5% of asthma-sufferers get appropriate treatment. Underlying this resistance there may be a certain element of rebellion on the part of those who suffer from asthma, an illness that bears a stigma. However, there is also misinformation – and not only among patients. In Minas Gerais, the team of infectologist Ricardo de Amorim Corrêa evaluated 102 people suspected of having asthma, who had been cared for by the Brazilian Public Health System (SUS) and referred to the pulmonology service of the Federal University of Minas Gerais. The first doctors who treated them told 90% of them to use only short duration bronchodilators, generally indicated for crises. “Bronchodilators don’t help control asthma over the long-term because they act on the muscles in bronchi that are responsible for the smallest number of symptoms aced in the crises,” explains Stelmach.

In Bahia, Alvaro Cruz has been showing that proper control of asthma is good for those who suffer from shortage of breath crises and also for the public health system. Since 2003, he has been developing an Asthma and Allergic Rhinitis Control Program (ProAR), which cares for 4,000 needy people in Salvador and Feira de Santana. Those who take part in the program get free asthma medication and periodic consultations with doctors, nurses and psychologists. At first sight more costly than SUS care, the ProAR strategy is, in fact, cheaper. Controlling asthma cut by 74% the number of hospital admissions in Salvador, generating a saving of R$ 4 million over four years. It also increased the family income of the patients, who went back to work.

Cruz sees some obstacles when it comes to rolling out the program nationwide. One is the distance between what is known about effective therapy and what the public service offers. Lapa e Silva, from UFRJ, agrees: “There’s been progress over the last eight years, but we still have to face the lack of access to medication and information that countries with a well-consolidated health system, such as England, achieved 30 or 40 years ago.”

The projects

1. Factors related to the difficulty of controlling asthma (05/58757-3); Type Regular Research Awards; Coordinator Rafael Stelmach – InCor/USP; Investment R$ 137,212.12 (FAPESP).

2. Evaluation of inflammation of the air pathways in asthma; Type Thematic Project; Coordinator Milton de Arruda Martins – FM/USP; Investment R$ 689,642.31 (FAPESP)

Scientific articles

Mauad, T. et al. Abnormal alveolar attachments with decreased elastic fiber content in distal lung in fatal asthma. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. v. 170, p. 857-62. 2004.

Souza-Machado, C. et al. Rapid reduction in hospitalizations after an intervention to manage severe asthma. European Respiratory Journal. 2009. In press.

Sembajwe, G. et al. National income, self-reported wheezing and asthma diagnosis from the World Health Survey. European Respiratory Journal. 9 September 2009.