Daniel Kondo

Daniel Kondo

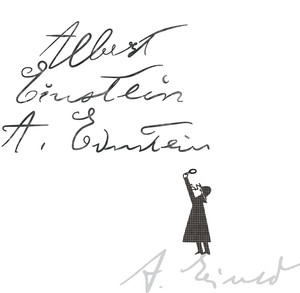

One of these behaviors is a rare or accidental change in the signature on one of the published papers, a kind of point outside the curve caused by a mistake or carelessness on the part of the author or the publication. Another pattern appears when researchers who sign their names one way early in their careers decide at a certain point to sign them another way—for example, women who change their surnames when they marry or divorce. Lastly, there is a pattern that is harder to detect, that of a researcher who signs in different ways without any concern about the merits of standardizing his or her signature.

The UFRJ researchers evaluated the incidence of those behaviors within two different environments. One was the database of the Digital Bibliographic Library Project (DBLP), which compiles the production by computer scientists and is frequently used as a reference in studies about ambiguity because the cases in which there are repetitive patterns of signatures have already been mapped. Also evaluated were 881 Brazilian researchers whose profiles in Google Scholar exhibited more than one kind of signature. These were selected from among recipients of productivity grants from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development.

It was found that the accidental substitution of a signature is the most frequent occurrence, accounting for 43% of the DBLP records and 53% of those in Google Scholar. A change made at a given moment in the researcher’s career was responsible for one-third of the cases in the DBLP and 18% in Google Scholar, while the frequent oscillation among signatures was shown to be a little more common among Brazilian authors in Google Scholar, with one-third of the cases, and less frequent in the DBLP, which includes researchers from various countries, at 25% of the total. One explanation for the frequent change in signature abbreviations among Brazilians is that their custom of using compound given names plus a surname leads to confusion. “We have a lot of surnames and use them freely, while authors from the United States are usually identified by only their first and last names,” explains Daniel Figueiredo who himself has been a victim of the problem. Most of his scientific articles are signed Figueiredo, D.R., but there are others with variants such as Figueiredo, Daniel, or Figueiredo, Daniel R.

The next step in the project was to evaluate the collaborative networks in which researchers who publish using more than one signature take part. It was observed that each of the three classes of behavior–-the occasional use of an alternate signature, changing a signature at a certain point in a career, and frequent use of more than one signature—presents collaborative networks that have clear and specific patterns. Those profiles can be useful in the future for formulating algorithms that are capable of helping identify ambiguous names. “Unmasking the ambiguity of names is a classic problem in computation; what we always try to do is to find all the labels, or types of signatures, that refer to a single individual,” says Janaina Gomide. “Our effort served to show the common causes of the ambiguity, which were already known intuitively but had not yet been measured, and to suggest that they be used in constructing new algorithms,” adds Figueiredo.

Daniel Kondo

Daniel Kondo

Researcher interest in this subject is explained both by the challenge of developing computer tools to solve a specific problem as well as the confusion that ambiguities cause when it comes time to measure the production by a given scientist. Much is lost during evaluations or bibliometric studies that require accurate information about authors. In a survey published in 2012 in the Sigmod Record, a quarterly publication by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM), Brazilian Alberto Laender, a professor in the Computer Science Department of the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), counted 17 different computational methods then in use for solving the problem of ambiguity. “Now there must be at least 30 different algorithms,” he reports.

The UFMG group developed three of those algorithms. One of them, known as HHC (Heuristic-based Hierarchical Clustering), was introduced in 2007 and began to be used by the DBLP, the same database that Daniel Figueiredo used in his study, as it was one of the simpler tools available to deal with the problem. Fruit of a master’s degree thesis defended by Ricardo Cota at UFMG, the HHC method combines the bibliographic data connected with a given signature and analyses it to see whether there are co-authors whose names recur. When a coincidence is found, the tool also considers whether the titles of the articles share certain words or whether the authors have attended the same scientific events. Efficiency in clearing up the ambiguity was rated at close to 80%. “The method started to be used because of its simplicity, but the search for ever more accurate algorithms has continued,” says Laender. “There are some situations in which no algorithm can solve the problem. Among authors from China, who frequently share the same surnames and where there is a huge volume of coinciding abbreviations, it becomes impracticable.”

A second method created by UFMG researchers was SAND (Self-training Associative Name Disambiguator), which groups bibliographic references according to common characteristics such as the presence of co-authors, title, and year of publication. Using artificial intelligence, SAND in its final stage is able to detect whether there are authors who, given their characteristics, should belong to certain groupings—and calculate the chances that such records are ambiguous references to other authors already present in the database. “Those classification techniques are quite well-known and one of our former doctoral students, Anderson Ferreira, now a professor at the University of Ouro Preto, adapted them for disambiguating. The SAND judges the references in different clusters until it reaches the conclusion that a certain author must be in that clusters,” Laender says. The third method developed at UFMG is the IDNi (Incremental Unsupervised Name Disambiguation), which combines several techniques and is used to evaluate new scientific papers that are added to the databases, automatically associating them with the profiles of existing authors and so preventing the emergence of new ambiguities.

Daniel Kondo

Daniel Kondo

A combination of different methodologies can produce more accurate results. Diego Raphael Amancio, a researcher at the Institute of Mathematical Sciences and Computation of the University of São Paulo (ICMC-USP), developed a method of solving ambiguities in signatures based on analysis of the networks in which the authors collaborated, but it is not limited to assessing who worked in partnership with whom. His strategy analyzes the patterns of connectivity of a broad network of researchers and depicts the status of each author in that universe. “By using concepts from the complex networks theory it is possible to generate graphs, evaluate the density of connections among authors and the average distance between the researcher whom I am studying and the others,” Amancio explains. He suggests using such measurements to describe production by one author and compare it with that of another who bears the same name in order to resolve ambiguity problems. Amancio was the principal author of an article published in 2015 in Scientometrics that demonstrated the efficiency of the use of that technique when combined with the widely accepted collaboration patterns analysis. In simulations using a set of three databases selected for the study, he demonstrated that the capacity for resolving ambiguities with that hybrid solution reached 85%, compared with 53% when only the traditional approach was used.

At the same time as it amplified the problem of ambiguity in bibliographic references, the increase in the volume of scientific production worldwide has inspired new solutions that do not involve algorithms. In 2012, an alphanumeric code was created that assigns each researcher a unique identification number. Dubbed ORCID (Open Researcher and Contributor ID) the number is now required by some institutions and funding agencies. It automatically bundles the production by each author (see Pesquisa FAPESP Issue No. 238). More than two million authors have already received their own identification number. “But not all researchers use this code and it is still necessary to use empirical methods in order to examine old libraries,” says Alberto Laender. Daniel Figueiredo observes that the knowledge accumulated in the effort against ambiguity of names may have other applications. “The tools can be used in other contexts,” he says. One of these involves grouping data from the medical records of a single patient who received care at different public hospitals or local clinics. “We are also thinking about studying the pattern displayed in the use of ambiguous names of actors and cinematographers in film libraries, like the Internet Movie Database,” Figueiredo reports.

Republish