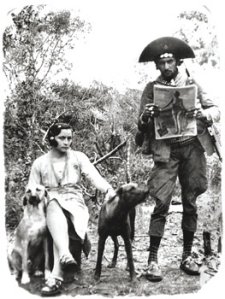

dissemination/"CANGACEIROS" EDITORA TERCEIRO NOMELampião and Maria Bonita by Benjamin Abrahãodissemination/"CANGACEIROS" EDITORA TERCEIRO NOME

In January 1935 a group of tourists from the State of Pernambuco were driving in a car when they came face to face with Lampião and his gang. Rummaging through the group’s luggage one of the bandits found a Kodak camera and handed it to his chief, who asked to whom it belonged. Terrified, one of them raised his finger. “I want you to take my picture,” retorted this king of bandits, posing. The man, making a great effort, took a picture, but warned: “Captain, that’s not a good position.” Jumping up and landing on his feet Lampião asked: “And is this any better?” Another photo was taken. When he freed the tourists, after taking everything from them, the “photographer” of the occasion asked him how he should send him the pictures. “It’s not necessary. Just have them published in the newspapers,” said the armed bandit.

When he was killed in July 1938, in the state of Sergipe, after having controlled the sertão, the arid hinterlands of the northeast of Brazil, for 12 years, the “deposed king’s” pockets were full of photographs of himself, such as those he used to distribute to his admirers in the famous organized parades that he indulged in when he entered towns he had conquered or was protecting. “The photographs of Lampião are just like the articles and stories about him, instruments of communication that allowed him to maintain a dialogue with those who lived on the coast and to challenge them. He established, therefore, a constant coming and going, which is what he wanted, between the world of the sertão hinterlands and that of the coast, between the archaism, which is attributed to him, and the tricks and tools of this modernity which fascinated him and which he knew how to use in his favor,” explains French Brazilian scholar, Élise Grunspan-Jasmin, the author of Lampião: o senhor do sertão [Lampião: the lord of the sertão hinterlands] (her doctoral thesis at the University of Paris IV), recently published by Edusp. In an area in which oral tradition prevailed, the greatest symbol of backwardness was a first rate marketer, who was also able to infuriate another master of this art: Vargas, a person who, starting with the New State, would fight against the imaginary world created by this “king”.

“The photographs of Lampião and his gang were a real provocation and were interpreted by the authorities as such. It was a dispute that was fought over image and the press became the new battle field in which photography started being used as a weapon,” notes this French woman, who also recently launched Cangaceiros (Publisher, Terceiro Nome), a collection of 90 photos that reveal the cunningness with which Virgulino Ferreira da Silva, by using photos and appealing to the imagination, transformed himself into Lampião. The book also shows the celebrated photos taken by the Lebanese traveling salesman Benjamin Abrahão, the lead character in the movie O baile perfumado [The perfumed dance], “official” photographer of the gang and author of O rei do cangaço [The king of the cangaço gangs] (1936), a film that shows the bandits and their leader going about their daily lives, with Lampião reading, sewing, having his hair combed by Maria Bonita and pretending to attack enemies, with a background of barely disguised laughter from his followers. Funnily enough, this was not the first film to deal with the theme: in 1925, Filho sem mãe [Motherless son] depicted a cangaceiro. From the 1920s to the 1990s, between short films, long features and documentaries, there were 50 examples of the type, which in Brazil already served as a theme for “northeasterns” [as opposed to the American “westerns”], porno-comedies and Glauberian allegories.

“The cangaço genre developed in a way that it maintained a sort of dialogue with other kinds of film in order to create itself. The theme became an integral part of adventure films, documentaries, comedies and erotic movies and the result was a national film genre that I believe will never cease to exist, because it can be interpreted in different ways and is always being revisited. This is our epic par excellence, a mythological universe that is fundamental to Brazilian culture,” analyses Marcelo Dídimo, author of the Ph.D. thesis O cangaço no cinema brasileiro [The cangaço gangs in Brazilian cinema], whose tutor was Március Freire, and which was defended this year at the State University of Campinas (Unicamp). The creator of his own myth, Lampião even cast some light upon social movements. “Until the late 50’s, the cangaço was rarely discussed, but since then there has been a resurgence of his character in a new context, in which the rural world became an object of interest again. As a result of the rise of the political awareness of the peasant, a Northeastern regional identity emerged and was crystallized around Lampião, who thus acquired a political dimension, as a hero in the struggle against the great landed properties,” notes Élise. So much so that in 1959 Francisco Julião declared in an interview that “Lampião was the first man in the Northeast, oppressed by the injustice of powerful men, to fight against the system of landed estates and arbitrariness. He’s a symbol of resistance.”

“Half a century later the Landless People’s Movement also sees Lampião as the incarnation of revolt against rural capitalism. What is the meaning of this paradoxical recovery, by left-wing movements, of a person who lacked awareness and had no political project to offer? He became the incarnation of values that are essential to the Northeast, yet at the same time he represents their very denial; this is where the whole power of this personality lies, as well as his ambivalence, shadowy ground that leaves the field wide open for any type of appropriation,” analyses the researcher. According to her the biggest question surrounding the cangaço is understanding how personalities who could be considered as having little intellectual capacity, with a sphere of power and influence restricted to a wretchedly poor region, managed to transform themselves into those who revealed the failings in a political, economic and social system and Brazil’s inability to forge its oneness at a time when society wanted to believe itself to be modern and unified. Lampião and a handful of armed bandits challenged not only the local leaders but also the central power. “Lampião, however, was not a revolutionary, but a rebel. He didn’t want to act upon the world in order to impose more justice, but to use the world as he wanted and to his own advantage. Faced with original injustice he proposed no alternative other than violence,” she observes.

The cangaço, in fact was born a long time before Lampião, who, nevertheless, thanks to his innate sense of propaganda, was responsible for the consolidation of its image. At first, entry into the world of lawlessness was the result of the need to avenge an insult or repair an injustice. Moving outside the law, the cangaceiros willingly excluded themselves from society in order to recover their honor and that of their families. In the hinterlands of the sertão, impregnated with a medieval spirit, as Professor Walnice Nogueira Galvão rightly observed in her Metamorfoses do sertão [Metamorphoses of the sertão], there was a link between violence and a certain type of heroism, to which popular literature and songs celebrating epic deeds lent some legitimacy. Lampião himself knew how to manipulate this form of communication when he justified his life as an outlaw as vengeance for the death of his father. “Lampião made vengeance his alibi and armed redress for insults a justification for the horror he imposed on the entire region,” Élise recalls. “He was a manipulator, a strategist gifted with a notable sense of communication that was surprising for the time and he quickly threw into the limelight the banditry of ostentation, in which decorations, ornaments and boastful pomp endowed the crimes with an extraordinary prominence.”

For the French academic, Lampião transmuted the “honorary” cangaço into a way of life, into a lucrative and glamorous profession, a means of acquiring material goods, wealth and a notoriety that allowed him to gain respect from a section of the wealthy class in sertão society and from some personalities from public and political life. During his time, violence and sources of income multiplied. To this end, he imposed a hierarchy upon the movement and organized a code of honor and respect for its internal laws. He also allowed women to join, including Dada, the wife of Corisco, who created the typical clothing the gang sported. Right from the start, Lampião understood the potential of the “image war”: in 1926 he “joined” the Patriotic Battalions, formed to fight against the Prestes Column. Politicians and Father Cícero even promised him the rank of captain, a title he would use for the rest of his life, without, in actual fact, ever having been one. In March of that year, when he was entering the town of Juazeiro with 49 outlaws, he was received like a hero by a crowd of 4,000 people to whom he distributed autographs. “From this moment on he was the first outlaw to look after his image and that is where his originality lies. He dramatized his life and used modern means of communication that were not part of his culture, such as the press and photographs.” He used to summon reporters to write about him.

“Lampião, cherishing the illusion that he had a greater role to play, exposed himself, paraded, strutted and showed off his gang: he had at last found his audience,” notes Élise. In 1936 he even reached the point of giving up a direct relationship with the press, meaning that they had to write about him via intermediaries he trusted; he was also concerned with what journalists wrote about him. He, therefore, accepted Benjamin Abrahão’s request to record his image because he knew that he could control the process to his own liking. With photographic material offered by Zeiss (which sent a pair of spectacles to the bandit as a gift), sponsored by Bayer (that wanted to take advantage of the film in advertising terms, as there are photos of Maria Bonita, with an advertisement for the aspirin based analgesic Cafiaspirina in the background), the Lebanese man, as film-maker, gave the armed bandits the freedom to show themselves as they wanted to be seen, to the point of annoying the federal government, and in particular the Press and Propaganda Department. “After a hard-fought campaign by the Vargas government against his film, and without the protection of the colonels, he was assassinated in 1938,” notes the researcher.

In this very year, the film’s lead character fell. Despite having managed to weave a network of clientele and corrupt relationships in the inland areas of the Northeast, at the outset of the New State, says Élise, “it became inadmissible that Lampião should continue to challenge not only the local authorities but the entire centralizing political system on which the structure of the newly-installed dictatorship rested.” After they were dead, he and his gang were beheaded, something unheard of in the war against vagabonds and bandits. “As a response to the allegation of the power and invulnerability of the bandit they exhibited his head as a trophy. Academics worldwide fought over it and Brazilian scientists, going against the tide of scientific progress, examined it, following the theories of Lombrosio.” Only in 1969 were the trophies buried. His myth, therefore, lives on. “It is for this reason that it’s necessary to understand how the death of Lampião, which was turned into a show, how his body and head, which were claimed by all the players of the time and even by his descendants, underpinned the images and representations haunt Brazil’s Northeastern region to this day.”

Republish