Nurse Lavinia Santos de Souza Oliveira first encountered an Indigenous population in the early 1980s. As an undergraduate student at the University of São Paulo (USP), she traveled with local doctors and other nursing students to Marabá, in Pará, to visit a village that was home to the Parkatêjê, better known at the time as the Gaviões. The group’s aim was to administer vaccines, but first they had to reach an agreement with the chief.

Krohokrenhum, the Parkatêjê chief, wanted to know if the vaccines were good. The nurse said they were. He challenged her to prove that she trusted the doctors administering the vaccine by getting injected before any of the Indigenous peoples offered up their arms. Oliveira asked a colleague to give her the tetanus vaccine, and only then did the chief allow the group to carry on with their work. “They are warriors, and I was very impressed by their pride,” recalls the nurse.

The experience was pivotal in shaping the choices she later made. Oliveira is the coordinator of human resources training for the Xingu Project, an outreach program led by the Paulista School of Medicine at the Federal University of São Paulo (EPM-UNIFESP), which has been developing activities to promote Indigenous health since the 1960s, and she likes to repeat the lessons she learned in the Indigenous villages. “Learning is more than mastering a theory,” she says. “It is the work that teaches us, as the Indigenous peoples know.”

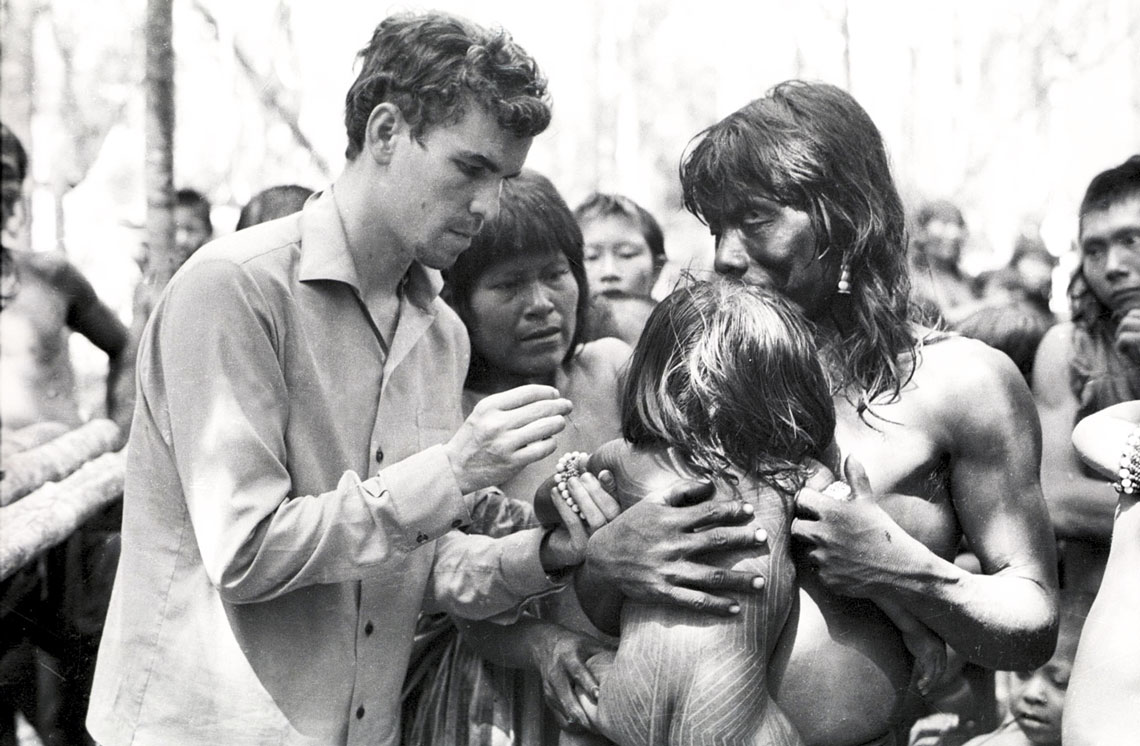

Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESPNewly graduated doctor Laercio Joel Franco gives a Kayapó child a vaccine in 1971Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESP

The project was born in July 1965, when seven university physicians, led by Roberto Geraldo Baruzzi (1929–2016), organized an expedition to assess the health conditions of the people living in the Xingu Indigenous Park, at the request of Brazilian sertanista Orlando Villas-Bôas (1914–2002), a key figure in creating the reserve in 1961 and its first director. At that time, the 16 ethnic groups that still inhabit the area totaled 1,135.

Some were threatened with extinction when infectious diseases they did not know about and could not control decimated their villages. In 1954, a measles epidemic killed 114 of the 640 Indigenous people living in the southern Xingu region in just one month. The Indigenous Park was intended to protect them from the pressures of the country’s urbanization, and nothing was more worrisome than the lack of medical care.

In the early years, the Xingu Project’s priorities were to vaccinate the population, care for the sick, and collect data on children’s nutritional status and chronic diseases. An agreement made by Villas-Bôas with the EPM allowed multidisciplinary teams to visit the park at least four times a year and during epidemics. Complex cases would be referred to the São Paulo Hospital, a philanthropic institution linked to the school.

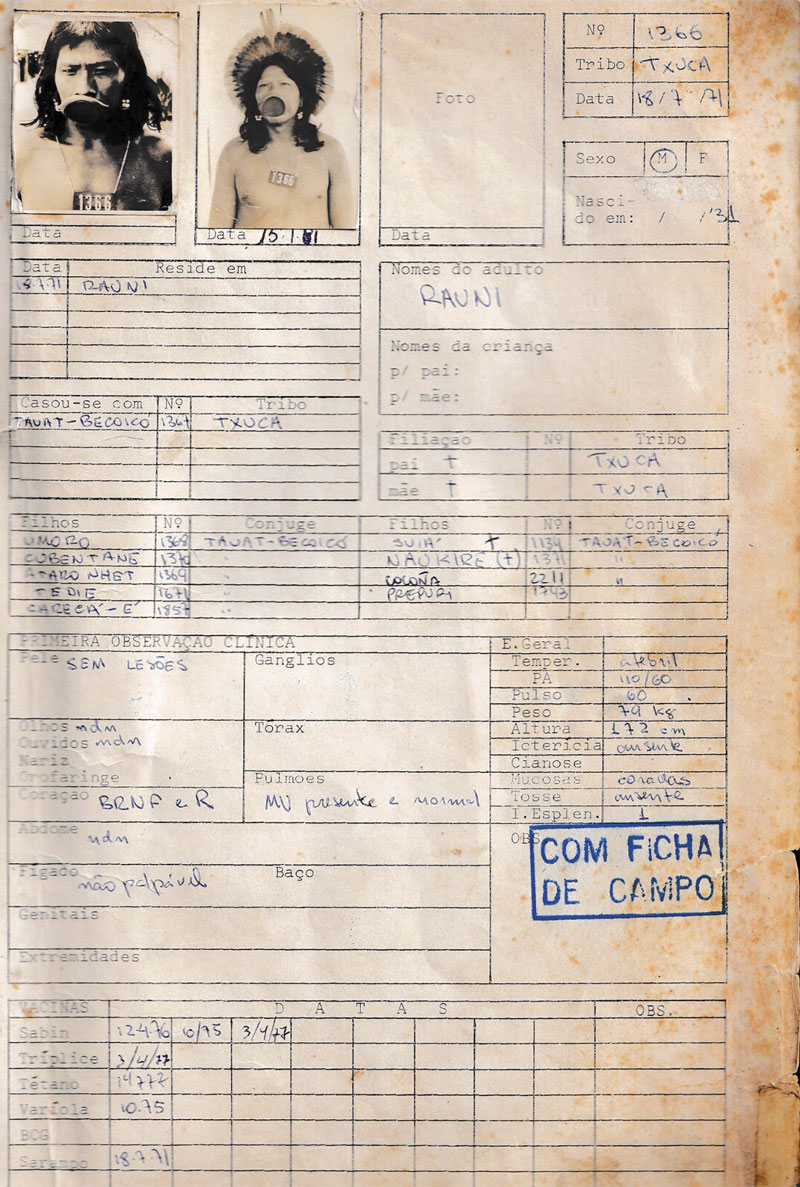

Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESPFile for chief Raoni MetuktireXingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESP

In a 2015 statement given to the São Paulo Association for the Development of Medicine (SPDM), which supports the São Paulo Hospital, Baruzzi estimated that the Xingu Project caravans mobilized 300 volunteers over four decades, including doctors, nurses, dentists, and students. “We went there to help and returned humbled by what we didn’t know,” says ophthalmologist Rubens Belfort Júnior, who visited the region for the first time in 1967.

From the very first trips, the Project’s doctors established a routine of filling out detailed forms with information on each Indigenous person they saw, allowing them to quickly build a comprehensive database on the reserve’s residents, including each person’s medical history, family relationships, and photographs that were updated from time to time. These forms were essential for monitoring the evolution of health conditions in the area.

Thanks to this diligence, the results of the program can be verified. In 1985, the doctors’ database showed that 2,555 Indigenous people lived in the Xingu, which meant that the park’s population had doubled in two decades. Diseases acquired during the first years of contact with outsiders had been controlled, and the mortality rate had dropped. The last recorded measles epidemic in the Indigenous territory occurred in 1979.

With Brazil’s return to democracy and the incipient Unified Health System (SUS), the project’s members began to invest in two other fronts: training people who could expand health efforts in the Xingu and strengthening the precarious healthcare system for the Indigenous residents. A first step was taken in 1989 with the creation of a specialized outpatient clinic in São Paulo, which still serves as a hub for Indigenous people seeking care at the University Hospital.

The first course, in the 1980s, was aimed at training 24 health monitors to assist patients at the park’s clinics and villages, taking advantage of the willingness of many Indigenous people to assist doctors and nurses in their work. “We realized that there was a need for training, and we talked a lot with the leaders to find the right methodology,” says health worker Sofia Beatriz Machado de Mendonça, who joined the Xingu Project as a student in 1981 and is now its general coordinator. In 1996, a class of 63 Indigenous health workers graduated after four years of training.

Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESPPulmonologist José Roberto Jardim, then a student, attends a group of Kayapó villagers, in 1970Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESP

Lavinia Oliveira joined the project the following year, after completing her master’s degree at USP’s School of Public Health, where she had analyzed a training program for nursing assistants in São Paulo. The first group of Indigenous assistants who took the course in the Xingu region graduated in 2002. That same year, Oliveira completed her doctorate at USP, where she studied the process of training Indigenous health workers and their integration into the SUS. Since then, UNIFESP has helped train 110 nursing assistants in the Xingu region and other Indigenous territories of Mato Grosso.

In 1999, the Ministry of Health reorganized the healthcare system by forming the Subsystem of Indigenous Health Care (SASI-SUS) and creating dozens of special health centers in the territories and shelters in the cities. The following year, through an agreement between the Ministry and UNIFESP, doctors from the outreach program became administratively responsible for the Xingu region, in charge of not only healthcare activities, but also hiring staff, building infrastructure, and distributing medicine and equipment.

The change created tension in relationships with Indigenous leaders, as Mendonça acknowledged when he took stock of the experience in his dissertation, which he defended at UNIFESP in 2021. “The equitable distribution of human and material resources among the different peoples was not an easy task,” he wrote. In 2004, the Ministry of Health took over the management of all Indigenous districts and began using the SPDM to hire the teams working in the Xingu region, through agreements that were periodically renewed.

Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESPBaruzzi talks to Claudio Villas-Bôas (bespectacled), Orlando’s brother, during a flight, in 1971Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESP

UNIFESP’s health workers then returned to focusing on support and training activities, but changes in the government and budget cuts made it difficult to continue the work. The second class of Indigenous health workers, with 62 students, graduated in 2011. The following year, the Xingu Project produced a comprehensive diagnosis of the health situation in the area, based on workshops held with Indigenous leaders, district managers, and health professionals working in the area, but the group’s recommendations were not implemented.

An issue that has concerned the project coordinators from the beginning and that has received greater attention is the link between biomedicine and Indigenous medicine. “Valuing [Indigenous] practices and knowledge is very important to increase resolution, create bonds of trust with professionals, encourage self-care, and enable preventive measures and health monitoring,” says Mendonça. “This has been sidelined in recent years due to the increase in medicine and services available in the territories.”

In the workshops held in Xingu Park in order to prepare the diagnostic report presented to the villagers and area managers, the health workers realized that the Indigenous people themselves were losing touch with the wisdom of their elders. Course participants were then encouraged to interview shamans, plant specialists, and others who knew the traditional practices of their villages, and to share the results of their research with the rest of the group in other phases of the course.

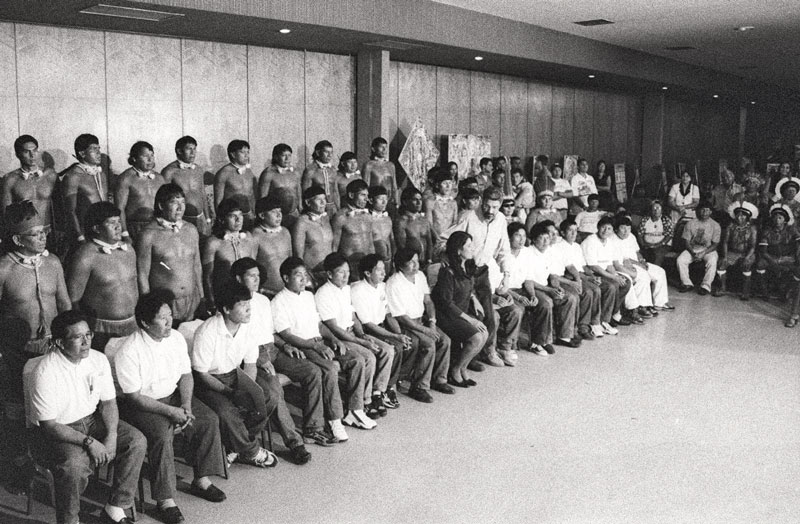

Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESPIndigenous health workers who participated in the project’s training course in September 2024: protesting firesXingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESP

“Many doctors in the city resist these practices and think we don’t respect their work, but the discussions have led some to rethink their stance,” says professor Autaki Waurá, a resident of one of the Waujas villages in the Xingu Indigenous Park, who is currently doing research for his doctorate in Anthropology at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). “Our knowledge can contribute to understanding the origin of diseases and help treat them.”

Studies by researchers from UNIFESP and other universities have shown dramatic changes in the epidemiological profile of the Indigenous populations, with an increase in chronic diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity. The first cases in the Xingu were recorded in the 1980s, but the situation has worsened as cities expand around the territory and as the Indigenous population increasingly consumes processed foods. The census carried out by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 2022 counted 6,204 Indigenous people living in the Xingu.

Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESPHealth worker Douglas Antonio Rodrigues instructs students in a Kuikuro village, in 2017Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESP

Preventive health measures

Genetic factors may also have contributed to the change, according to an international study conducted in 2010, in which UNIFESP researchers participated by analyzing blood samples from the Xavantes in search of a marker associated with a higher risk of diabetes and other diseases (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 182). The coordinators of the Xingu Project want to expand the study and track this marker, especially in people impacted by expanding agribusiness in the Amazon, such as those living in the Xingu and the Panará. “This would help us plan preventive and educational measures,” says health worker Douglas Antonio Rodrigues, who coordinated the program from 1996 to 2010. (Rodrigues and Sofia Mendonça met in college and married in a Kuikuro village, where they are treated like family.)

Another idea being discussed is the creation of a civil society organization of public interest, which would allow them to raise funds from donors and international agencies to fund projects and expand its activities. According to a recent survey carried out by the program’s coordinators, its researchers have worked on 18 projects financed by funding agencies since the 2000s and have produced 22 master’s theses, 20 doctoral dissertations, and 148 articles published in indexed scientific journals.

Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESPThe first class of Indigenous nursing assistant students graduates in 2012, in Cuiabá (MT)Xingu Project Collection / EPM-UNIFESP

This year, the program resumed the training courses for those working in the Xingu, with a class of 210 basic healthcare workers and financial support from the state government of Mato Grosso, where the reserve is located. At the end of September, the doctors and nurses sent on the first scheduled cycle were surprised by smoke from the fires in the region and their impact on the Indigenous communities. “They had started to plant cassava, but they lost everything because of the fire and can’t replenish their food stocks,” explains Mendonça.

The planting and fire-control techniques developed by the Indigenous people, with support from the Socio-Environmental Institute and other organizations, have proved inadequate, damaging new crops and jeopardizing food security in the villages. The consequences could be increased processed food consumption and, in the long term, chronic diseases such as those that are worrying doctors in the Xingu. “It is a perverse cycle that needs to be broken,” she says.

The story above was published with the title “Caring for the village” in issue 345 of November/2024.

Republish