A novel infectious disease originating from China has found its way to Brazil. Scientists know relatively little about the disease, but are making successive discoveries as it continues its global spread. It’s the late nineteenth century, and the bubonic plague has hit the port city of Santos, on the coast of the state of São Paulo. The country is in dire need of a vaccine to protect its citizens.

In 1900, the Brazilian government responded to the bubonic pandemic by creating the Federal Serum Therapy Institute in Manguinhos, a northern district of Rio de Janeiro, on an abandoned farm overlooking Guanabara Bay. The new Institute was headed by Baron Pedro Afonso, who owned and was then producing smallpox vaccines at the Municipal Vaccine Institute. He invited Oswaldo Gonçalves Cruz (1872–1917), a 28-year-old serology and microbiology researcher at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, to join him as technical director. The next year, São Paulo’s governor created Instituto Serumtherapico (the Serum Therapy Institute), now renamed Instituto Butantan (the Butantan Institute), with a similar mandate.

Within six months, the Federal Serum Therapy Institute delivered its first doses of serum for treatment and a vaccine to prevent the bubonic plague. But the Institute’s managers had differing views about its future. According to historian Jaime Larry Benchimol, a researcher at Casa de Oswaldo Cruz (COC-FIOCRUZ), the young scientist envisaged an institute that also engaged in education and research, modeled after the Pasteur Institute in France. But his vision was at odds with that of the Baron, who ultimately left the Institute in 1902.

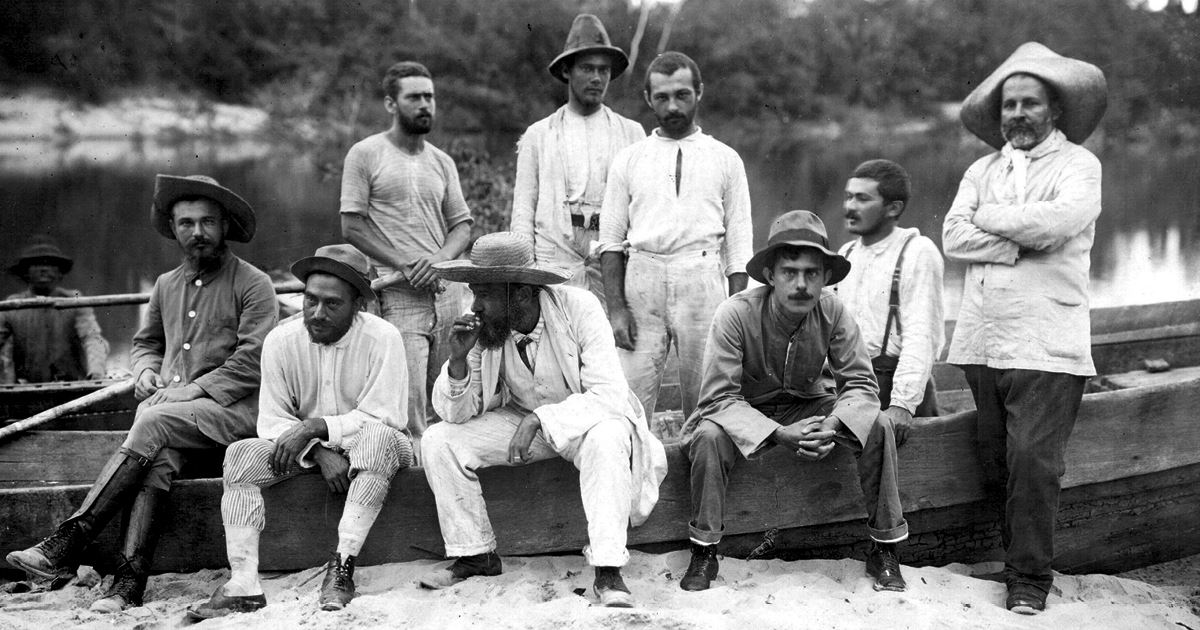

Casa de Oswaldo Cruz archives / FIOCRUZ

Oswaldo Cruz in PetrópolisCasa de Oswaldo Cruz archives / FIOCRUZOswaldo Cruz replaced him as head of the facility, and a year later was appointed chief of the General Directorate of Public Health (DGSP). There, he started a large-scale effort against the three biggest public-health threats facing early twentieth-century Brazil: the bubonic plague, smallpox, and yellow fever. He made case reporting mandatory, and launched a campaign to eradicate rats, the carriers of the fleas which spread the bacterium Yersinia pestis. Teams of health surveillance agents were deployed to hunt for rodents, while the DGSP offered residents small cash payments in exchange for rats, dead or alive. Rio de Janeiro’s poor soon made hunting rodents their livelihood, with some fraudulently breeding rats for sale to the government.

From riot to recognition

Oswaldo Cruz’s strategy against yellow fever was to eliminate breeding sites for the mosquito Stegomyia fasciata (later renamed Aedes aegypti), which Cuban physician Carlos Finlay (1833–1915) had identified 20 years prior as the vector of the disease. Initially attracting little attention from the international medical community, his theory would only gain acceptance in 1900—the same year the Institute was created—when germ theory superseded the previously popular miasma theory, or the belief that diseases are caused by foul air.

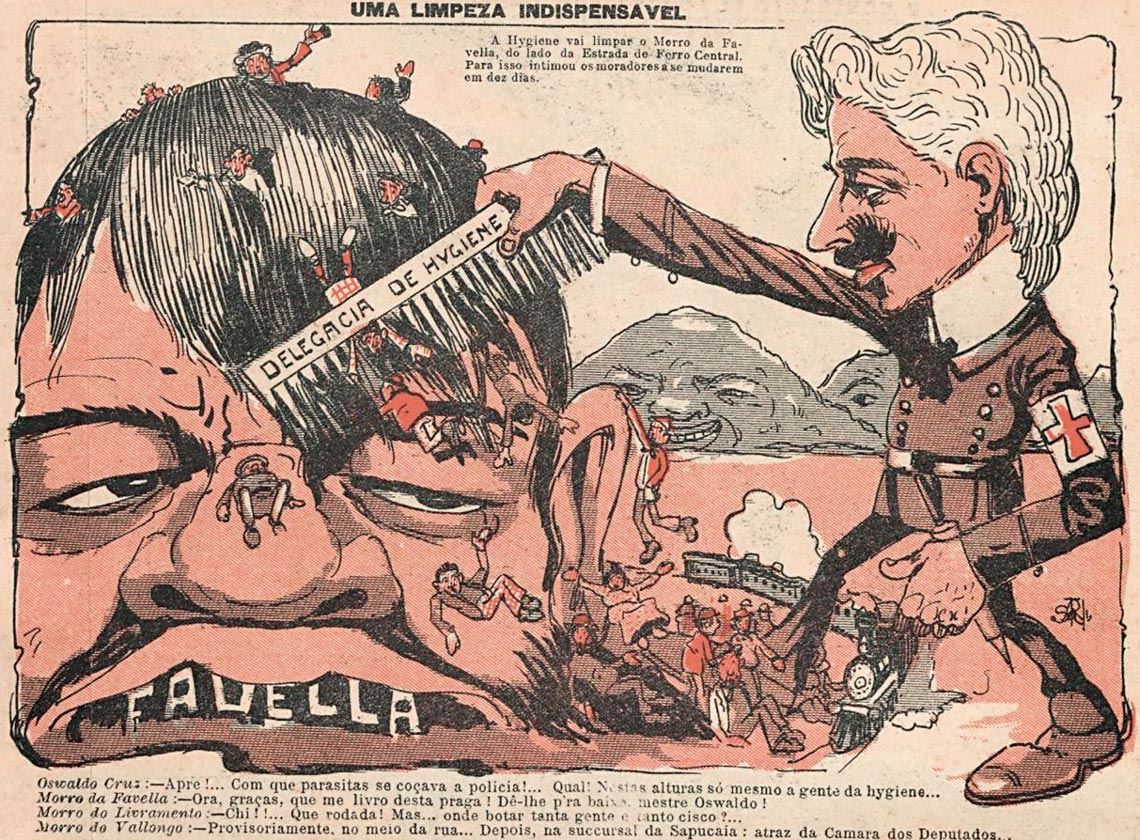

Cruz divided the city into 10 sanitary districts, each under the oversight of a health officer, and introduced strict sanitary regulations that imposed fines for the owners of properties found to pose a health hazard. The sanitarian’s efforts became the subject of jokes and political cartoons, and earned him the jocular nickname “Captain Mosquito Killer.” But humor soon turned into public outcry against the “sanitary police”, who could enter people’s homes without permission from homeowners, and even remove sick people against their will. Public outrage escalated into a riot in 1904 when the smallpox vaccine became mandatory.

WikiCommons

Oswaldo Cruz in a political cartoon featured in the magazine O Malho in 1907WikiCommonsThe measure, says Benchimol, was met with broad opposition: from positivists who opposed the state’s curtailing of individual liberties, to people who feared the vaccine could make them look like oxen, as it was produced from material collected from cattle with cowpox, a bovine disease similar to smallpox. The day after the measure was introduced, rioters took to the streets and had to be contained by the police. The riots lasted approximately one week, resulting in 30 deaths, 110 injuries, and 945 arrests. “The populace paid a twofold price: not only did they endure harsh repression, but in 1908 they suffered from a smallpox epidemic that killed almost 6,400 people,” recounts Benchimol.

“But the same country that rioted over a vaccine later created one of the most robust immunization programs in the world, successfully eradicating several diseases,” says FIOCRUZ Chairwoman Nísia Trindade Lima. “The recent measles outbreak, however, is a timely reminder that these accomplishments can’t be taken for granted.”

Casa de Oswaldo Cruz Archives / FIOCRUZ

Carlos Chagas in Lassance (1909), Minas Gerais, observing young Rita, one of the first identified cases of the disease that would bear his nameCasa de Oswaldo Cruz Archives / FIOCRUZDespite the opposition they had to contend with, the teams led by Oswaldo Cruz succeeded in curbing all three epidemics. In 1907, the yellow fever epidemic in Rio de Janeiro was declared contained, a feat that earned Cruz international recognition, including a gold medal in the 14th International Congress of Hygiene and Demography in Berlin, Germany. In 1908, the Institute was renamed after its director, who would retain his position until 1916.

Researchers at the Institute soon began to receive invitations to assist in efforts against diseases affecting remote areas of Brazil. Scientific expeditions were dispatched to several states. It was during a 1909 expedition to the northern portion of Minas Gerais, in the small town of São Gonçalo das Tabocas (present-day Lassance), that Carlos Chagas (1879–1934) discovered American trypanosomiasis, or Chagas disease. In a tropical medicine “triple play”, he identified the protozoan that causes the disease, naming it Trypanosoma cruzi in honor of Oswaldo Cruz; the insect vector (kissing bugs); and the clinical characteristics of the illness, then often mistaken for malaria or hookworm infection. More than 80 years later, in 1990, a test kit for diagnosing the disease would lead to FIOCRUZ’s first international patent.