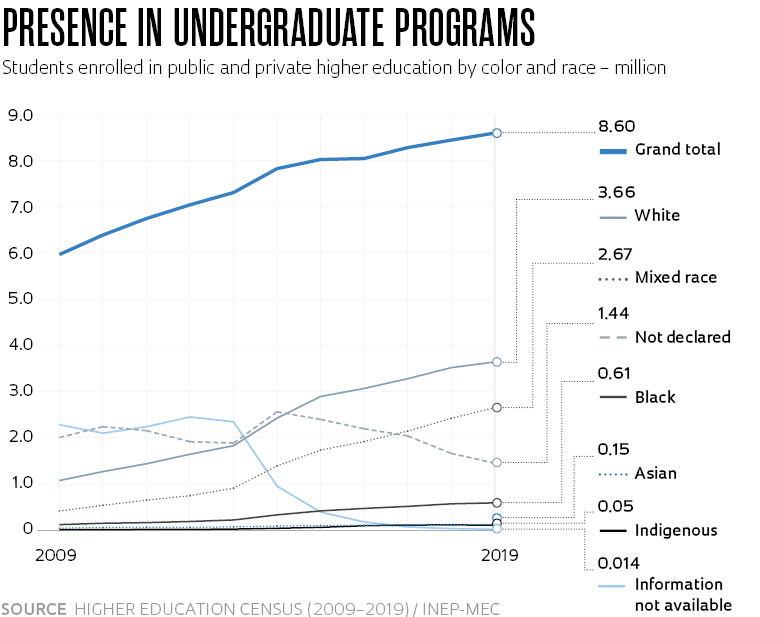

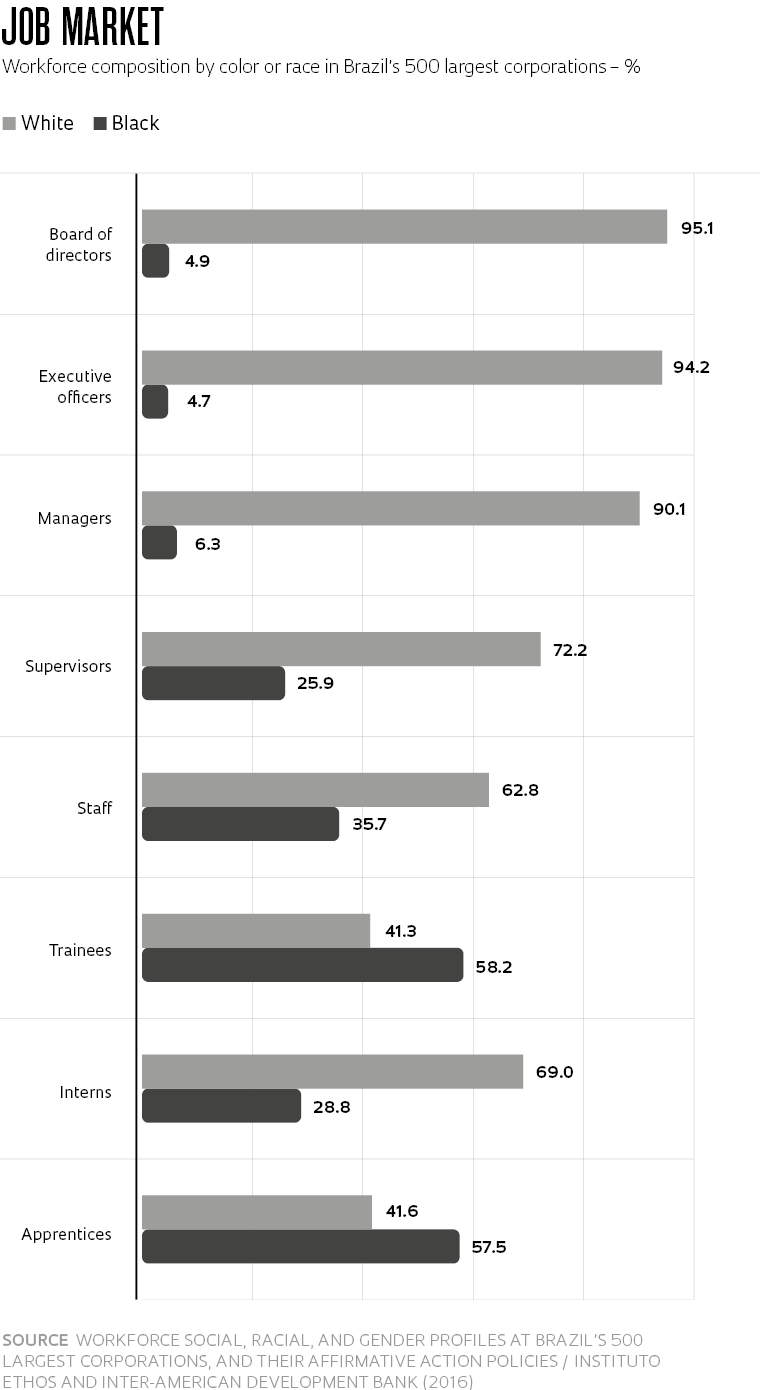

First launched around two decades ago, affirmative-action policies for black, brown, and indigenous people have helped to drive diversity in higher education, particularly in the most competitive programs—such as engineering and medicine—and in southern universities. But despite the increased access to undergraduate and graduate university programs, black employment levels in both the public and private sectors have remained low. Management and better-paid positions are still largely held by white men.

A research project—titled Latin American Anti-racism in a Post-Racial Age—conducted at the University of Cambridge and the University of Manchester from 2017 to 2018 with funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the UK, found that affirmative action, laws criminalizing racism, and awareness campaigns were some of the most commonly adopted measures in Latin American countries in the mid-2000s. In Brazil, where black and mixed-race people represent 56.2% of the total population, according to data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), the first institutions to implement affirmative action in admissions in the early 2000s were the Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ), Bahia State University (UNEB), and West Zone State University (UEZO). In 2004, the University of Brasília (UnB) and the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA) followed suit.

In 2012, Federal Law no. 12 711 required 50% of spots in federal universities to be reserved for students from public schools. Half of those spots are reserved for youth in households with an income per capita of less than one-and-a-half minimum wages. The other half is allocated to other students with higher per-capita incomes. Within each income bracket, universities are required to enroll a percentage of black, mixed-race, and indigenous applicants that reflects the makeup of the relevant state’s population. This means that the total percentage of black, mixed-race, and indigenous students at a university must be equivalent to the total percentage of those minorities in the state population. “By taking both race and income into account, this type of affirmative action benefits society more broadly and not only people of color—it includes white students from public high schools, and excludes black students from private schools, who presumably have had access to a better secondary education than students in public schools,” explains economist Hélio Santos, chairman of Oxfam Brasil.

Reflecting these policies, in 2018 black and mixed-race students accounted for 50.3% of enrollments in public universities, according to the IBGE. “Article 7 of the affirmative action law is due to be amended in 2022 to include mechanisms for tracking students’ academic and professional careers, including program completion or abandonment, entry in the job market, and pay grades,” notes Santos, who in 1984 founded and initially managed the São Paulo Black Community Council, one of the first organizations in Brazil to develop, advocate for, and track racial equity policies.

In an effort to measure the impact from affirmative action in Brazilian federal universities, in 2018 Adriano Souza Senkevics, an education sociologist at the National Institute for Education Studies and Research (INEP), partnered with Ursula Mattioli Mello, an economist at the Barcelona School of Economics, in Spain, to assess shifts in the profiles of undergraduate students as a result of those policies. By intersecting data from the Higher Education Census and the National High School Examination (ENEM), they compared the profiles of students entering university between 2012 and 2016 in terms of their academic background, self-identified color and race, and per-capita income. Although they recognize that the expansion of university places since the 1990s, the creation of higher learning institutions outside major cities, and the increased offering of nighttime programs has also influenced the recent shifts in student profiles, Senkevics and Mello argue that affirmative action can be credited for a 50% increase in black and indigenous university students in Brazil.

A paper published in 2019 with preliminary findings from their research shows that, between 2012 and 2016, the shift in student profiles was most marked at the Federal University of Ceará (UFC), the Federal University of Santa Catarina (UFSC), the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), the Federal University of Paraná (UFPR), and UnB, especially in the most competitive university programs—such as medicine, law, and engineering. “These institutions and programs have been significantly transformed by affirmative action,” says Senkevics. He notes that the South of Brazil saw the highest relative gain in black, indigenous, and public-school students entering higher education, with UFSC, to name an example, recording a 120% increase in the presence of black, mixed-race, and indigenous university students coming from public schools. “In 2012 those minorities accounted for 6.4% of admissions to UFSC, and by 2016 they accounted for 14.2% of the total,” he notes in comparison.

Research shows that the academic performance gap between students admitted under affirmative-action policies and those admitted through regular admission pathways is now small or nonexistent

Another example is the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS), where black, mixed-race, and indigenous students from public schools rose from 8.7% to 15.6% over the same period. Among the programs with the most marked changes in student profiles, says Senkevics, was the Bachelor of Laws program at UFC—from a 1% share of black, mixed-race, indigenous, and low-income students from public schools to 27% in 2016. In the electrical engineering program at UFSC, the share of minorities went from zero to 13.7%, while the medicine program at the Federal University of Rondônia (UNIR) recorded a 38% gain.

In São Paulo, Senkevics cites as an example the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), the first public university to adopt affirmative-action policies. The share of black, mixed-race, and indigenous students from public high schools climbed from 16.14% to 24.23% over the same timeframe. In the university’s medicine program, the presence of these minority groups increased from 8.20% in 2012 to 19.35% in 2016. “But affirmative-action initiatives have had a lesser impact on the more popular programs. In some cases the number of minority students has even fallen in these programs,” says Senkevics. “Minority students appear to be attempting admission to more competitive programs.”

In 1993, physicist Sônia Guimarães became the first female and black professor to join the Department of Fundamental Physics at the Aeronautics Institute of Technology (ITA). During her first month at the department, there were not more than 4 female students out of a class of 120. She now sees the university’s diversity rates improving since it implemented affirmative-action policies in 2019. “Out of the 160 new students admitted to ITA in 2021, 17 are women, and 3 self-identify as black. I don’t know whether they were benefited by affirmative-action policies, but it’s the first time I’ve seen this happening since joining the institute,” says Guimarães, who has just won a patent for an infrared radiation sensor she developed.

Recent research has shown that the academic performance gap between students admitted under affirmative action policies and those admitted through regular admission pathways is now small or nonexistent. A 2020 study by researchers at São Paulo State University (UNESP) collected data from 2014 to 2017 on around 30,000 students at the university, including affirmative action students and those enrolled via regular pathways, and found no significant disparity in academic performance.

Similarly, a 2017 survey codeveloped by Jacques Wainer, a professor of electrical engineering at UNICAMP, and Tatiana Melguizo, a professor of economics at the University of Southern California, compared the performance of around 1 million students in the National Student Performance Examination (ENADE) from 2012 to 2014, and found that those admitted under affirmative action policies either matched or exceeded the performance of their classmates. “People of color have gone from being the subjects to being the authors of research, producing knowledge that is strategic for Brazil,” says Santos of Oxfam, describing his own personal experience. With a bachelor’s degree in economics and a master’s and PhD in finance, in the last 15 years he has worked in the field of corporate social responsibility, advising corporations on matters involving ethnic and racial diversity.