“Dona Flor: This character is coming along nicely. The last two scenes I churned out quickly—the first in a day, although the second took me four: it was the scene of Vadinho’s arrival, after all. I’ve now started on part five. Today I’m tackling the first scene. It’s in rough form—needs rewriting. This fifth section is proving difficult.” That’s how celebrated Bahian author Jorge Amado (1912–2001) described his effort in crafting a pivotal scene from Dona Flor and her two husbands (1966) in a 1962 letter to his wife, fellow writer Zélia Gattai (1916–2008). “At first glance, Amado’s prolific body of work might suggest he was a haphazard writer who didn’t dwell on craft,” says Marcos Antonio de Moraes, a professor of Brazilian literature at the University of São Paulo (USP). “But his correspondence tells a different story: Amado was methodical, allowed his ideas time to mature, and often anguished over his writing as a work in progress.”

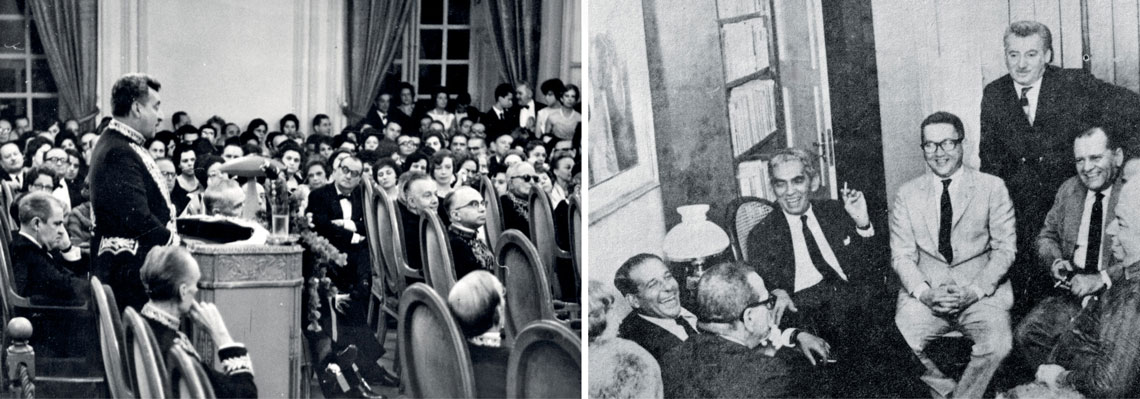

Moraes is one of 56 contributors to the newly published Dicionário crítico Jorge Amado (A critical dictionary of Jorge Amado; EDUSP), edited by historians Marcos Silva (1950–2024), formerly of USP’s School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH), and Nelson Tomelin Jr. of the Federal University of Amazonas (UFAM). Ten years in the making, the book is a collection of essays on Amado’s oeuvre written by scholars from various disciplines, including literary studies and anthropology. Among other works, it explores Amado’s 23 novels written since the 1930s—titles such as Jubiabá (1935) and Gabriela, clove and cinnamon (1958). It also includes entries on moments that shaped Amado’s trajectory, such as his 1961 induction speech at the Brazilian Academy of Letters.

According to Tomelin Jr., one of the aims of the publication, which was produced with support from the Amazonas State Research Foundation (FAPEAM), is to help expand and refresh the public’s understanding of Amado’s work and its historical context. “Amado has an enormous readership in Brazil and abroad, due in large part to the vitality of his prose, the thematic reach of his novels, and their resonance with the times in which they were written. But the critical reception in Brazil has often been mixed,” notes the researcher. One possible reason, suggests Eduardo de Assis Duarte, professor emeritus at the School of Languages and Literature at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), is precisely Amado’s immense popularity with readers. “Some in academia dismiss him as a ‘lightweight’ author of serialized fiction,” Duarte says, “but as early as the 1930s, he was already tackling weighty national issues—like youth homelessness in Captains of the sands [1937].”

According to journalist and historian Joselia Aguiar, author of Jorge Amado: Uma biografia (Jorge Amado: A biography; Todavia, 2018), critical engagement with Amado’s work began in the 1930s. “In his early years, Amado enjoyed strong critical acclaim, drawing praise from names like Oswald de Andrade [1890–1954] and Antonio Candido [1918–2017],” says Aguiar, who earned her Ph.D. in 2019 at the University of São Paulo’s Department of History, where she wrote her thesis on the Brazilian author. “That changed in the 1970s,” she explains. “Critics increasingly approached his work through a gender lens. One notable example was Walnice Nogueira Galvão’s critique of Tereza Batista: Home from the wars (1972), which cast the novel in a negative light and shaped academic opinion thereafter.”

Zélia Gattai Collection / Fundação Casa de Jorge Amado 2 From left to right: Zélia Gattai, philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and Jorge Amado with Mãe Senhora (seated) in Salvador, 1960sZélia Gattai Collection / Fundação Casa de Jorge Amado 2

Aguiar notes that as Brazil’s Black movement gained momentum in the late 1970s, authors such as Amado—who touched on racial themes—came under fire for portraying race relations in a way that some viewed as overly conciliatory. “Today, though, even in these critical arenas, his work is being revisited and reassessed,” Aguiar says. This return has been fueled in part by a growing number of Black students entering Brazilian universities over the past 25 years, bringing new perspectives into academia. Another key factor is the republishing of Amado’s work by Companhia das Letras beginning in 2008. “What’s still lacking,” she adds, “is more engagement from within the literary field itself—a closer look at what made his work so successful and the mechanics of his storytelling.”

Another recurring critique—raised by literary scholars such as Alfredo Bosi (1936–2021) of USP—is that some of Amado’s early works, especially from the 1930s to the 1950s, leaned too heavily into political propaganda. After joining the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB) in 1931, Amado began writing overtly ideological texts—books and pamphlets commissioned by the party—many of which were never reprinted. A prime example is Homens e coisas do Partido Comunista (Men and things of the Communist Party; 1946), which is part of a series published by Horizonte, a publishing house run by the PCB. In 61 pages, the book tells the story of communist activists portrayed as heroes in the fight against fascism during Brazil’s Estado Novo regime (1937–1945).

“This ideological phase of Amado’s career is often criticized not just for its communist alignment, but for how he became a de facto party propagandist—promoting international socialism through the framework of socialist realism,” says Lincoln Secco of FFLCH-USP, who authored the dictionary entry on Homens e coisas do Partido Comunista. Despite alienating literary critics, these partisan works propelled Amado to international prominence. His biographical novel The Knight of Hope (1942), written at the party’s request and chronicling the life of leftist leader Luís Carlos Prestes (1898–1990), was translated into 21 languages, including German, French, and Japanese. “The Communist movement invested heavily in publishing to promote its causes,” notes Secco.

In a 2024 doctoral thesis defended at FFLCH-USP, aided by research grant funding from FAPESP, historian Geferson Santana explored how Amado, along with fellow Bahian intellectuals Edison Carneiro (1912–1972) and Aydano do Couto Ferraz (1914–1985), engaged in debates on race and class in early twentieth-century Brazil. “In the 1920s, the PCB denied that racism existed in Brazil—and even embraced the notion of racial whitening,” Santana explains. “The three intellectuals, who joined the party in the 1930s, were among the key figures who pushed the PCB to take up racial issues,” he says. “Their goals included fighting racism and religious intolerance, and increasing Black workers’ representation within the party.”

ReproductionsCovers of Jubiabá and the U.S. edition of Gabriela, clove and cinnamonReproductions

Amado’s overtly political literary phase extended into the 1950s. His final ideological work is widely regarded to be the trilogy The bowels of liberty (1954), written during his exile in Europe. The trilogy’s three volumes—Bitter times, agony of night, and Light at the end of the tunnel—paint a sweeping portrait of Brazilian political life just before the 1937 coup led by Getúlio Vargas. According to Antonio Dimas, a professor of Brazilian literature at FFLCH-USP, the trilogy reads like Amado’s final tribute to the Communist Party—his way of closing a chapter before leaving the party in 1956. “It’s as if he were saying: ‘This trilogy is my discharge—my dues paid in full,’” says Dimas.

Many scholars, including Dimas, point to Gabriela, Clove and Cinnamon (1958) as a watershed moment in Jorge Amado’s literary career. He sees this work as the moment Amado left political propaganda behind to become a pure novelist. “This was a different Amado—with more humor and irony. After Gabriela, he would go on to create unforgettable heroines like Tieta and Dona Flor,” says Dimas. “But it’s worth noting,” he adds, “that even in The Country of Carnival [1931], which he wrote at 18, women already appear as strong and resilient—even when they’re relegated to the margins of the story.”

Eduardo de Assis Duarte of UFMG, however, sees no sharp rupture in Amado’s literary trajectory. He makes this case in his new book, Narrador do Brasil: Jorge Amado, leitor de seu tempo e de seu país (Jorge Amado: Narrator of his time and nation; Fino Traço Editora, 2024). In Duarte’s view, Amado consistently explored the themes of gender, class, and race throughout his literary career. “He always wrote about free women, in charge of their own lives,” says Duarte. “He went so far as to place two sex workers at the center of his stories—Tieta [1977] and Tereza Batista: Home from the wars.”

Owing to works such as Gabriela, clove and cinnamon, Jorge Amado earned a spot in the Guinness World Records in 1996 as the world’s most translated author. His works have been translated into 49 languages. Amado’s novels began reaching U.S. readers in the 1940s, owing largely to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s (1892–1945) Good Neighbor Policy, a diplomatic strategy launched after World War II (1939–1945). As part of that policy, the U.S. State Department sponsored efforts to publish international authors in the U.S. market.

Natonal Archives / Correio da Manhã / Wikimedia Commons | Revista Brasileira – Brazilian Academy of Letters / Wikimedia CommonsTwo photos of Amado (standing) from the 1960s—on the left, at a gathering attended by President João Goulart (to the left of the lamp), and at the Brazilian Academy of Letters (right)Natonal Archives / Correio da Manhã / Wikimedia Commons | Revista Brasileira – Brazilian Academy of Letters / Wikimedia Commons

Amado made his American debut with The violent land, published in Brazil in 1943 and translated into English in 1945. The English edition was published by American publishers Alfred Knopf (1892–1984) and his wife Blanche Knopf (1894–1966). “In their publishing under the Good Neighbor Policy, the Knopfs were especially drawn to authors whose fiction shed light on Brazilian history,” explains Marly Tooge, a translator who published an article on the topic in 2024. “That included not just Amado, but also Érico Verissimo [1905–1975].”

After Gabriela was published in the United States in 1962, Jorge Amado landed on The New York Times best-seller list—where he stayed for a full year. “It would seem that Amado’s departure from Marxist ideology in the 1950s helped pave the way for his success in the U.S.,” says Tooge. “But it also had to do with the way his books were translated.” Her 2009 master’s thesis at FFLCH-USP was later turned into the FAPESP-funded book Traduzindo o BraZil: O país mestiço de Jorge Amado (Translated as BraZil: Jorge Amado’s mixed-race nation; Humanitas, 2012). She notes how translators James Taylor and William Grossman softened the novel’s social critique in English and amplified its sensual appeal. “This kind of sanitization was also done with other Amado novels published in the U.S., like Dona Flor and her two husbands,” she adds. “Publishers placed an emphasis on the ‘exotic’ side of his stories in marketing campaigns. In contrast, Amado’s ideological works saw more success in Europe.”

Beyond fiction, Amado was also a prolific correspondent. Joselia Aguiar notes how the archive of letters compiled by Amado and his wife Zélia Gattai—which is now preserved at the Jorge Amado Foundation in Salvador—holds approximately 70,000 letters. In her doctoral thesis, Aguiar focused on Amado’s correspondence between the 1950s and 1980s with Spanish-language authors such as Cuban poet Nicolás Guillén (1890–1954) and Chilean Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda (1904–1973). “Through these letters, Amado built a network of both emotional and cultural-political camaraderie. He saw literature in Latin America as a tool of resistance to imperialism,” says Aguiar. “He believed it was essential to discover and express a truly national voice through literature.”

Project

Debates on race and class by communist intellectuals: Printed material and social networks in Brazil (1937–1957) (nº 19/09513-7); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Marisa Midore Deaecto (USP); Beneficiary Geferson Santana de Jesus Investment R$144,934.33.

Scientific article

TOOGE, M. D. B. Entre guerras e traduções: Literatura brasileira em inglês, a USIA e Alfred A. Knopf. Interdisciplinar – Revista de Estudos em Língua e Literatura. Vol. 40, no. 1, pp. 61–74. 2024.

Books

DUARTE, E. de A. Narrador do Brasil: Jorge Amado, leitor de seu tempo e seu país. Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2024.

SILVA, M. & TOMELIN JUNIOR, N. (ed.). Dicionário crítico Jorge Amado. São Paulo: Edusp, 2024.