Chorographical map of the province of Paraná, National Library, Rio de Janeiro, Cartographic Records

Map of the province of Paraná and inset of São Pedro de Alcântara settlement in 1859Chorographical map of the province of Paraná, National Library, Rio de Janeiro, Cartographic RecordsFrom 1845 to 1889, the Portuguese Empire worked to establish indigenous settlements throughout the provinces of Brazil. These settlements were agricultural colonies that were intended to attract indigenous peoples and transform them into rural workers. They were created under an agreement between the Brazilian government and the Vatican agency responsible for sending Catholic missions to different corners of the world, then known as the Sacred Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith (Propaganda Fide) and later rechristened the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples. The Vatican wanted to boost its presence in Brazil by converting Indians to Christianity. The Brazilian Imperial Crown, on the other hand, was concerned about expanding its control over the nation’s territory, recruiting workers to grow coffee and harvest rubber, and building roads to connect far-off regions. With these interests in mind, Emperor Pedro II signed a decree that allowed Capuchin Franciscan missionaries to emigrate from Italy to Brazil to organize and run indigenous settlements.

The plan was that through the work of the missionaries, who were hired as servants of the Empire, the Indians would be “civilized” and catechized, so they might later join the European immigrants who were arriving in Brazil and setting up their own colonies. Furthermore, by encouraging the Indians to leave their land and move to the area of the settlements, the government hoped that immigrant farmers and workers could occupy the native lands. Some indigenous village leaders received military titles and were drafted to serve in conflicts, including the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870). In addition to growing food, the Indians were also recruited to build roads, a job for which they received a wage.

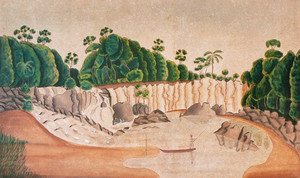

J. H. Elliott – National Library, Iconography Section

View of Salto dos Dourados on the Paranapanema RiverJ. H. Elliott – National Library, Iconography SectionMarta Amoroso, professor in the Department of Anthropology at the University of São Paulo (USP), has published Terra de Índio: Imagens em Aldeamentos do Império [Indian land: images from the Empire’s settlements] (Terceiro Nome, 2016), based on FAPESP-funded doctoral and post-doctoral research. The book analyzes the experience of a system of settlements in Paraná, particularly its central hub, São Pedro de Alcântara, one of the longest-lived in Brazil. Relatively little research has been done on indigenous peoples in the 19th century, says Amoroso, who believes the gap is a result of the day’s catechizing efforts, because missionaries like the Capuchins tried to spread the idea that all Indians had been converted and thus diminish their historical identity.

Based on a trio of primary sources – reports and letters held at the Capuchin Franciscan Archives at the Holy Basilica of St. Sebastian, in the neighborhood of Tijuca, Rio de Janeiro; accounts by traveling naturalists who crossed the region; and works by ethnologists such as the German Curt Nimuendaju – Amoroso sought an interpretation that would highlight the experience of the settlements from the Indian’s perspective. In doing so, she revealed a new dimension of the experience, previously examined primarily in keeping with the official viewpoint. According to the researcher, religious records on the São Pedro de Alcântara settlement provide information on how different ethnic groups occupied these settlements and coexisted with them. They show that Kaingang leaders were involved in settlement management and stayed on even after the Capuchin Franciscans had ended their mission, as is the case of the present-day São Jerônimo da Serra Indigenous Land, in Paraná. The same records also tell how groups of Indians fled in the wake of epidemics and the conflicts that erupted upon forced contact with enemy groups.

J. H. Elliott – National Library, Iconography Section

Portrait of Chief Pahi Kaiowá of Santo Inácio do Paranapanema settlementJ. H. Elliott – National Library, Iconography SectionAppealing to the palate

In her book, Amoroso also describes how the establishment of these settlements was linked to the organization of military colonies, reflecting the intention to use intimidation to delimit Brazil’s internal borders to the benefit of European landowners and immigrants. Maria Luiza Ferreira de Oliveira, professor of the history of Brazil at the Guarulhos campus of the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp), explains that military colonization was embraced as a public policy precisely when the government was looking to increase its rule over indigenous lands in order to raise coffee in the Southeast and sugar and cotton in the Northeast. “They also expected to find potential riches in the forests inhabited by the Indians,” she says. Within this framework, the notion governing the establishment of the military colonies was that of peaceful approach, that is, an effort was made to persuade the Indians to join the settlements. “But mixing threats with enticements was actually the Empire’s way of doing a more effective job of persuasion,” the researcher argues.

Lying on the banks of the Tibagi River, the São Pedro de Alcântara settlement was the center of a network that stretched the entire length of the Paranapanema River, from São Paulo to Paraná. The settlement was once home to some 4,000 Indians from four ethnic groups: the Kaingang, of the Macro-Jê linguistic trunk, and the Kaiowá, Nhandeva, and Mbyá, all of which speak Guarani. This number included Indians who moved to the area of the settlements as well as those who already lived in the vicinity. Amoroso’s research tells how each indigenous group interacted with the settlement. Each group’s motivation depended on specific interests: the Guarani-Nhandeva went to receive the clothing and medicine handed out by the friars, but did not settle there, whereas the Kaingang and Guarani-Kaiowá took part in agricultural labor and activities at the São Pedro de Alcântara settlement distillery.

Photos Franz Keller, 1865; Newton Carneiro, 1950, Iconografia Paranaense (Curitiba: Impressora Paranaense, 1950)

The Kaingang Indian Vei-Banj, of São Pedro de Alcântara settlementPhotos Franz Keller, 1865; Newton Carneiro, 1950, Iconografia Paranaense (Curitiba: Impressora Paranaense, 1950)Missionaries and government personnel lived inside the settlements themselves, whereas the Indians stayed in villages nearby. There was a tendency for the Indians to migrate between different hubs and in some cases return to their land of origin. “The missionaries tried to lure the Indians by appealing to their palates, with the idea that they would have a bodily experience of Christian civilization by receiving salt, sugar, coffee, and cachaça,” Amoroso says. It was believed that these attractions would entice the Indians to abandon their savage ways. But according to Empire policy, once an Indian had been “civilized,” he no longer had a right to settlement resources. The parameters for determining whether an Indian had been “civilized” were his willingness to work the crops and wear clothing and his abandonment of forest life. But some “civilized” Indians would move to other settlements and pretend they were still “savage” so they could ask for clothing, tools, food, and other provisions.

After 1845, the year of the first wave of immigration under the settlement program, some 100 Capuchin Franciscans arrived from Italy. Their earliest accounts described the Indians as childish in nature and endowed with limited intellectual capacity. However, Amoroso’s research shows how coexistence shifted this perception over the years. “They began to see the Indians as people with a pure, unadulterated mentality,” the researcher says. An example of this can be found in the writings of Friar Thimoteo de Castelnuevo (housed at the Holy Basilica of St. Sebastian), who lived at the São Jerônimo de Alcântara settlement for 50 years. By the end of his life, according to Amoroso, the cleric was “exalting the grandeur of the Indian soul, contrary to the hypocrisy of civilization.”

Photos Franz Keller, 1865; Newton Carneiro, 1950, Iconografia Paranaense (Curitiba: Impressora Paranaense, 1950)

Captain Manuel Arepquembe, chief of the Kaingang Indians of São Pedro de Alcântara settlementPhotos Franz Keller, 1865; Newton Carneiro, 1950, Iconografia Paranaense (Curitiba: Impressora Paranaense, 1950)In another account, Friar Luís de Cimitille expressed the frustration he felt as he struggled to catechize Manuel Arepquembe, captain-chief and head of the Kaingang at the São Jerônimo settlement. In his memoirs, the friar reports on his many futile attempts to convert the Indian, who refused to accept the existence of a supreme, omnipresent god. When the friar realized that Arepquembe was going to the settlement to receive goods, the cleric came to the conclusion that his missionary enterprise had failed. In closing his account, he complained that the Indian had never even learned to cross himself and that, at their final meeting, he had laughed as he bid the cleric a “sarcastic farewell.”

Convenience factor

According to Amoroso, the fact that many Indians were seeking to satisfy their own interests when they visited the settlements is borne out by the failed attempts to make São Pedro de Alcântara economically productive by growing coffee and tobacco. These experiments were not successful because the Indians expressed no interest in coffee and were much too interested in tobacco and thus depleted the harvest. Later, when the missionaries decided to try their hand at planting sugarcane and also built a rum distillery, they had help from the Kaingang and Guarani-Kaiowá, who took up the work because they liked the liquor. “Some ethnic groups were also seeking support when they visited the settlements – weapons, for example, which they used in their clashes with rival groups,” the researcher explains.

Photos Franz Keller, 1865; Newton Carneiro, 1950, Iconografia Paranaense (Curitiba: Impressora Paranaense, 1950)

São Pedro de Alcântara settlement depicted in an 1865 sketch by German artist Franz KellerPhotos Franz Keller, 1865; Newton Carneiro, 1950, Iconografia Paranaense (Curitiba: Impressora Paranaense, 1950)These conclusions stand in contrast with the standard interpretation of settlement policy, Amoroso says, which has generally assigned indigenous peoples a passive role. “Even when ‘civilized’, the Indians sustained their beliefs and used the settlement policy to their own advantage,” argues anthropologist Paula Montero, professor at the USP Department of Anthropology and deputy coordinator of Human and Social Sciences for FAPESP, who sees the reconstruction of Indian subjectivity as one of the prime achievements of Amoroso’s research. Montero studied the experience of the settlements run by Christian missionaries in two research projects: “Christian Missionaries in the Brazilian Amazon” (2001-2007) and “Missionary Textuality: Salesian ethnographies in Brazil” (2008-2010).

As to the paucity of research on the indigenous question in the 19th century, Montero explains that in the 1950s, the field of ethnology started conducting on-site surveys of indigenous peoples in an effort to understand their cosmological universe, an approach that dominated the field until quite recently. Moreover, Montero says, the past 50 years have brought a tendency for members of religious orders to be blamed for destroying indigenous peoples, a perspective that undermined interest in the study of relations between missionaries and Indians in the field of anthropological study.

Book

AMOROSO, M. Terra de Índio: Imagens em Aldeamentos do Império. São Paulo: Terceiro Nome, 2014, 246 pp.