A collaboration between experts in history, computing, and cognitive sciences is helping to show how ideas emerged and thrived shortly after the French Revolution (PNAS, April 17). Researchers from Indiana University and Carnegie Mellon University, both in the USA, used data mining techniques to analyze transcripts of 40,000 speeches made at the National Constituent Assembly, France’s first post-revolution parliament, which met from 1789 to 1791. The texts are available in the French Revolution Digital Archive and were studied using a method that combines information theory with statistics to track word use patterns in assembly debates. While representatives on the left of the political spectrum used innovative rhetoric to present their ideas, the more conservative members used familiar word combinations to oppose change. “At the beginning of the revolution, there’s just a whole lot of newness going on. Eventually, some of it sticks, and people gravitate to it and keep working with it,” said historian Rebecca Spang, a researcher at Indiana University and coauthor of the study, according to the news website Eurekalert. Eventually, the effectiveness of charisma in debate was partially neutralized by the creation of committees to deliberate on specific topics. “These committees ended up being centers of power through their specialized knowledge,” said computer scientist Alexander Barron, lead author of the study.

RepublishComputation

Data scientists reconstruct the rhetoric of the French Revolution

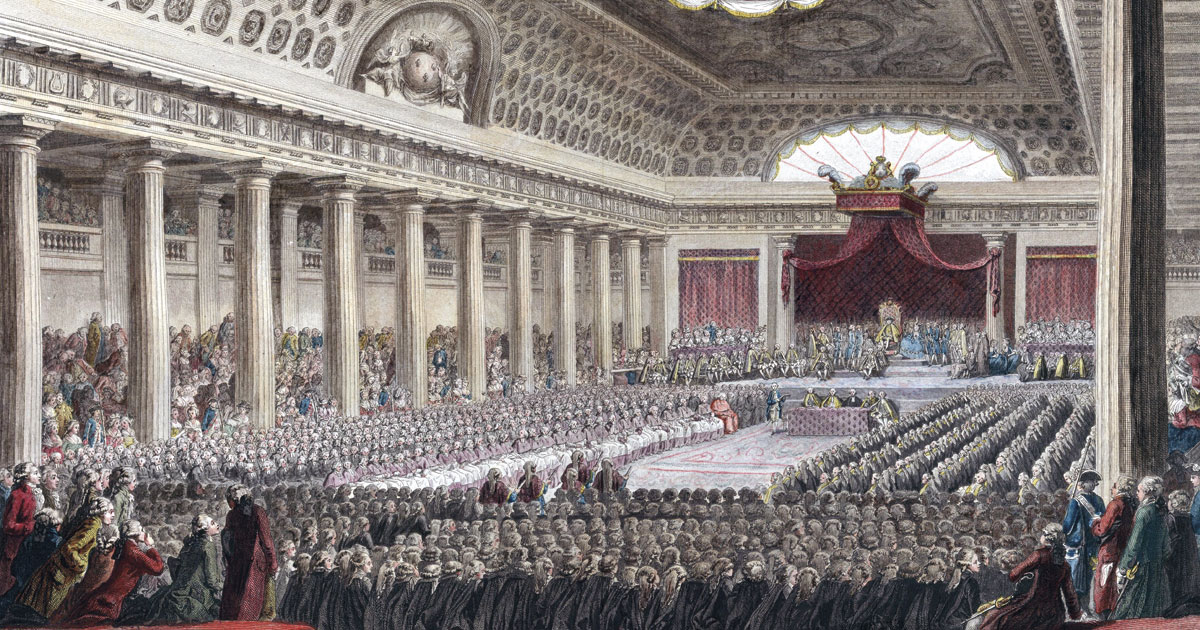

Opening of the Estates General in Versailles on May 5, 1789, engraving by Isidore-Stanislas Helman (1743–1806) based on a sketch by Charles Monnet (1732–1808)

Isidore-Stanislas Helman / Bibliothèque Nationale De France / Wikimedia Commons