The Brazilian federal government has pledged to reinstate funding for science, technology, and innovation in the upcoming years, although at a currently undisclosed pace and scale of recovery. This will bring new responsibilities for the scientific community and policymakers in restoring research capabilities and setting priorities. Recent years have been challenging. The National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (FNDCT), Brazil’s primary science-funding program, has suffered successive budget cuts since 2016, with the Ministry of Finance citing the need to stay within the constitutional budget cap.

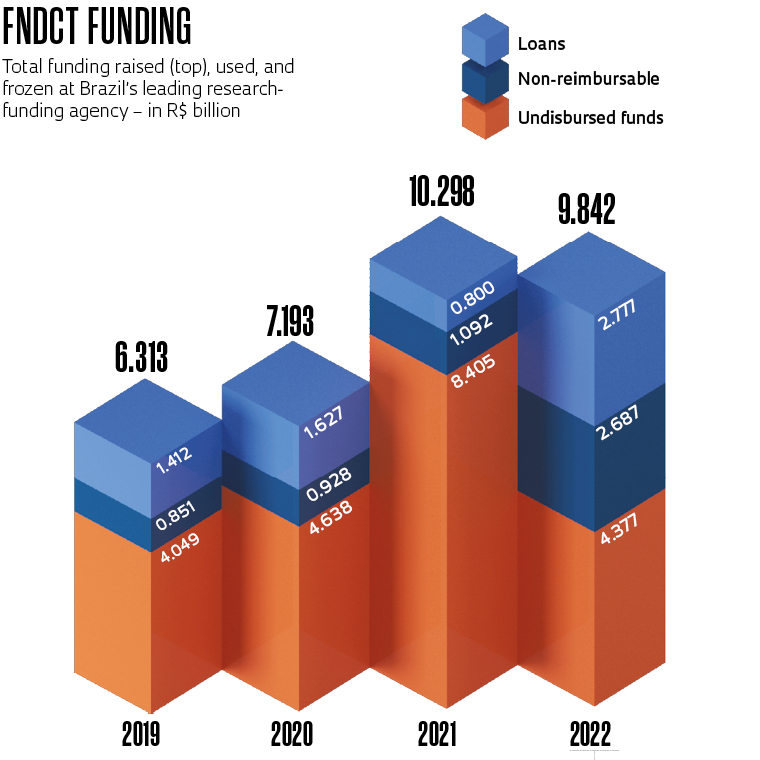

The funding crunch has been in contrast with a substantial increase in FNDCT revenue, which currently stands at R$10 billion per year—the FNDCT receives a percentage of tax revenue in 14 different industries, paid into Sectoral Science and Technology Funds. Analyses by the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA) have found that only around R$1 billion in nonrepayable FNDCT funding was invested annually from 2019 to 2021 (see chart). In current figures, this represents the lowest level of funding for science and innovation projects across research institutes and industry this century.

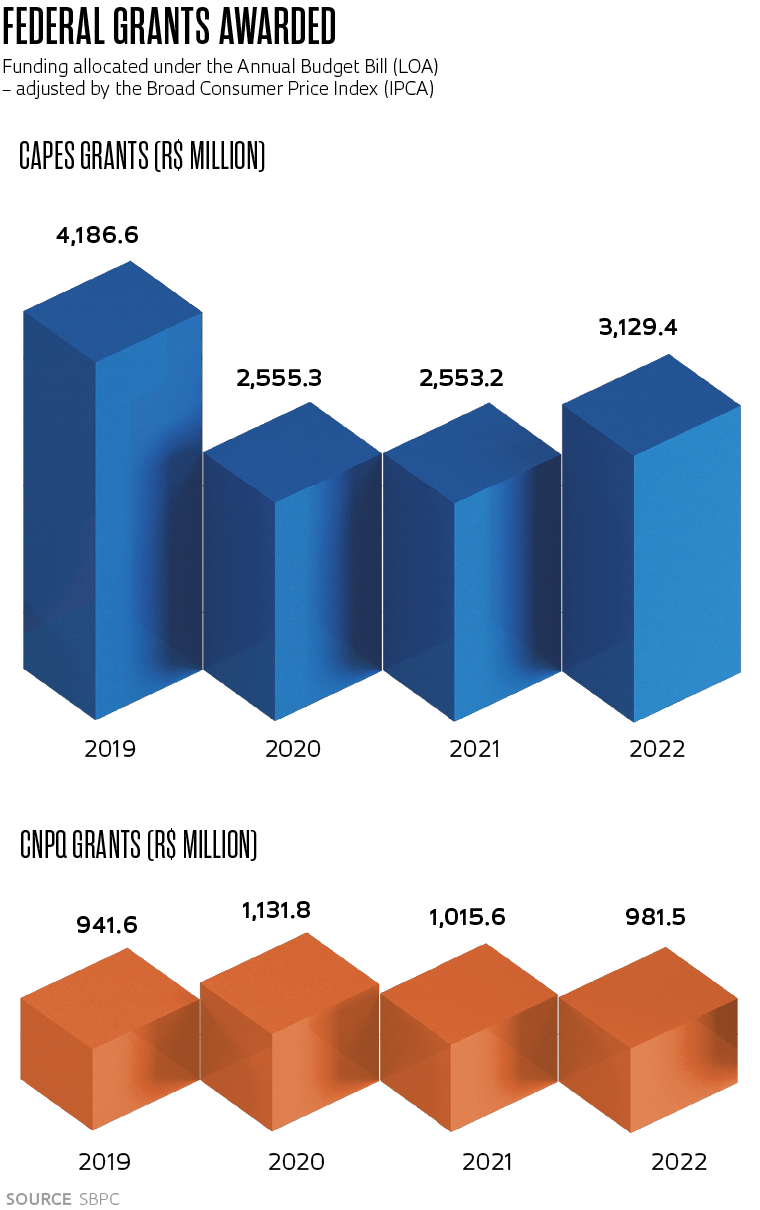

According to the Knowledge Observatory, an organization operated by federal and state university faculty unions, the “knowledge budget” for nationwide science funding dropped from R$25.3 billion in 2019 to R$17.1 billion in 2022. This includes spending and investment at federal universities and funds received from research-funding agencies such as the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), linked to the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI), and the Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education (CAPES), linked to the Ministry of Education. “The combined budget cuts at research-related ministries amounted in aggregate to R$130 billion during the previous administration,” says Mayra Goulart, a professor of political science at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ) and the Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), who heads the Knowledge Observatory. The organization is currently compiling a list of projects and laboratories that were shut down for lack of funding, which it plans to publish later this year.

The spending cuts have affected research grants, projects, and maintenance expenses but not mandatory spending, such as faculty payroll at federal institutions and universities. But despite faculty members continuing to work, they have often been understaffed due to a lack of new hires to replace retiring professors. Brazil’s graduate education system, the training ground for the country’s top researchers, has become dilapidated. Partly because of the pandemic, the number of newly trained PhDs in 2020 and 2021 was just slightly more than 20,000, which is 4,000 fewer than the contingent trained in 2019 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 315).

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPRadiopharmaceutical production at IPEN, São PauloLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

Biomedical researcher Helena Nader, who chairs the Brazilian Academy of Science, says the curtailed research funding, coupled with an extended freeze on federal master’s and doctoral fellowship awards, largely explains the declining number of new PhDs. Since 2013, CNPq and CAPES master’s fellowships have been frozen at R$1,500, and doctoral fellowships at R$2,200. “Demand for graduate training has fallen due to a lack of prestige associated with science careers, with the government seemingly viewing them as dispensable. Why would I spend years of my life studying for a career that is unappreciated in Brazil,” asks Nader, a researcher at the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). She believes the road to rebuild science capabilities will be a long one. “In the short term we will need to address urgent needs such as making fellowship awards more competitive and restructuring the MCTI, which has fallen into disarray in recent years.”

Economist Fernanda De Negri, who heads IPEA’s Center for Research on Science, Technology, and Society, highlights the need to accurately assess the current state of human resources in strategic industries, such as information technology and renewable energy. “We need to determine the extent to which we have the researchers we need to tackle the challenges ahead, after several years with fewer PhDs being trained,” she says. This also applies to research infrastructure: “In recent years there have been very few projects to upgrade laboratories at public universities, and it is likely that many of them are now lagging far behind their global peers. We recently conducted an assessment of laboratories linked to the oil industry, and found a higher rate of obsolescence compared to previous assessments. All of these will need to be upgraded.”

Although federal budget containment was partly eased in 2022, the approved budget for 2023 still had R$4 billion in curtailed FNDCT funding. According to analyses done by the Brazilian Society for the Advancement of Science, several agencies will have another difficult year if unable to get a funding boost. CNPq, for instance, planned to spend R$1 billion on fellowships in the year, the same amount as last year, but the budget for the research projects where those fellows would work fell from a paltry R$35 million in 2022 to a piddling R$28 million in 2023. CNPq’s new chair, physicist Ricardo Galvão, says the agency and CAPES will shortly announce an increase in fellowship awards—from undergraduate to postdoctoral—using funds under a spending cap waiver approved in Congress in December. He admits, however, that the agency will struggle to expand investment in 2023, as the congressionally approved budget remains restrictive.

At her inauguration on January 2, the new Minister of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI), electrical engineer Luciana Santos, the first woman to assume the position, said one of her first priorities would be to reinforce the budget by spending the R$9.9 billion earmarked for the FNDCT in 2023. She also pledged to increase fellowship awards and take steps to improve gender inclusion and diversity. The budget deal in congress involved negotiations to prevent lawmakers from voting on Provisional Measure no. 1,136, issued in August 2022, allowing it to expire. Had it been voted on, it would have delayed to 2027 the entry into effect of a law forbidding any curtailment of the FNDCT. This law had been passed in Congress in 2020 following extensive discussion among researchers, business leaders, and lawmakers. Under the now expired provisional measure, R$14 billion could have been frozen over the coming four years, according to calculations prepared by SBPC. “We are experiencing a veritable blackout in science funding in Brazil,” Santos said in her inaugural speech. “This funding was meant to be invested in innovation and infrastructure and institutes doing research in areas such as energy, oil, mobility, the environment, and information technology. It is also a violation of legislation passed by Congress.”

CEITECCEITEC facilities in Porto Alegre: resuming abandoned programsCEITEC

Even if research budgets and grants are immediately reinstated, a full recovery is only expected to occur in 2024, when the constitutional spending cap is likely to be replaced by another mechanism to contain public debt. Pedro Wongtschowski, head of the National Confederation of Industry’s (CNI) Mobilization for Business Innovation (MEI) initiative, a coalition of more than 500 different companies, believes that four fronts need to be tackled in the short term. The first would be investing on an emergency basis in science and technology infrastructure to restore capabilities. “Federal universities are in shambles, and public research institutions are unequipped and have aging staff. We need to restore their ability to fulfill their mandate,” says Wongtschowski. He suggests prioritizing funding for projects that are nearing completion, such as the Sirius synchrotron light source (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 269).

A second front, says Wongtschowski, would be helping private companies to step up their own innovation efforts. “This would require improvements to the current funding framework, including tax incentives in general and the ‘Lei do Bem’ in particular,” he says, referring to a piece of legislation enacted in 2005 that introduced tax incentives for research and development (R&D) to boost innovation. The third front would be supporting tech companies and university-industry collaboration. “The innovation law contains provisions allowing faculty and students from public institutions to start tech companies in the private sector, but this has been underutilized. Startups are a valuable source of innovation for large corporations, which can either acquire or partner with them to accelerate their own innovation processes.”

Lastly, he notes the importance of investing in technology uptake. “There’s lots of technology out there that never sees adoption in the public or private sector, and which could be valuable in modernizing small and medium-sized companies,” he says. As a practical step, Wongtschowski suggests expanding funding for the Brazilian Agency for Industrial Research and Innovation (EMBRAPII), created under the MCTI in 2014. “EMBRAPII had just a third of its original budget. It was able to raise an additional R$2 billion in public and private funds for use in innovation projects in industry and for building capabilities at the 70 science and technology institutes collaborating on those projects.”

Minister Luciana Santos has indicated she will prioritize projects that were put on hold in the last few years. Among these is the Brazilian Multipurpose Reactor (RMB). The project was launched in 2008 by the National Nuclear Energy Commission (CNEN) to give Brazil standalone capacity to produce radiopharmaceuticals—agents used to diagnose and treat a wide range of diseases, which the country currently sources mostly from overseas. In 2012 the RMB project was included in the federal government’s multiannual plan with a budget of R$500 million, but the physical works in Iperó, a town in São Paulo State, never got off the ground. Last year, the Institute for Energy and Nuclear Research (IPEN) had to suspend its production and supply of radiopharmaceuticals to hospitals in Brazil for several weeks after it ran out of funds to import materials due to the Ministry of Finance’s budget freeze, which has since been reversed (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 309).

InpeA satellite under development at INPEInpe

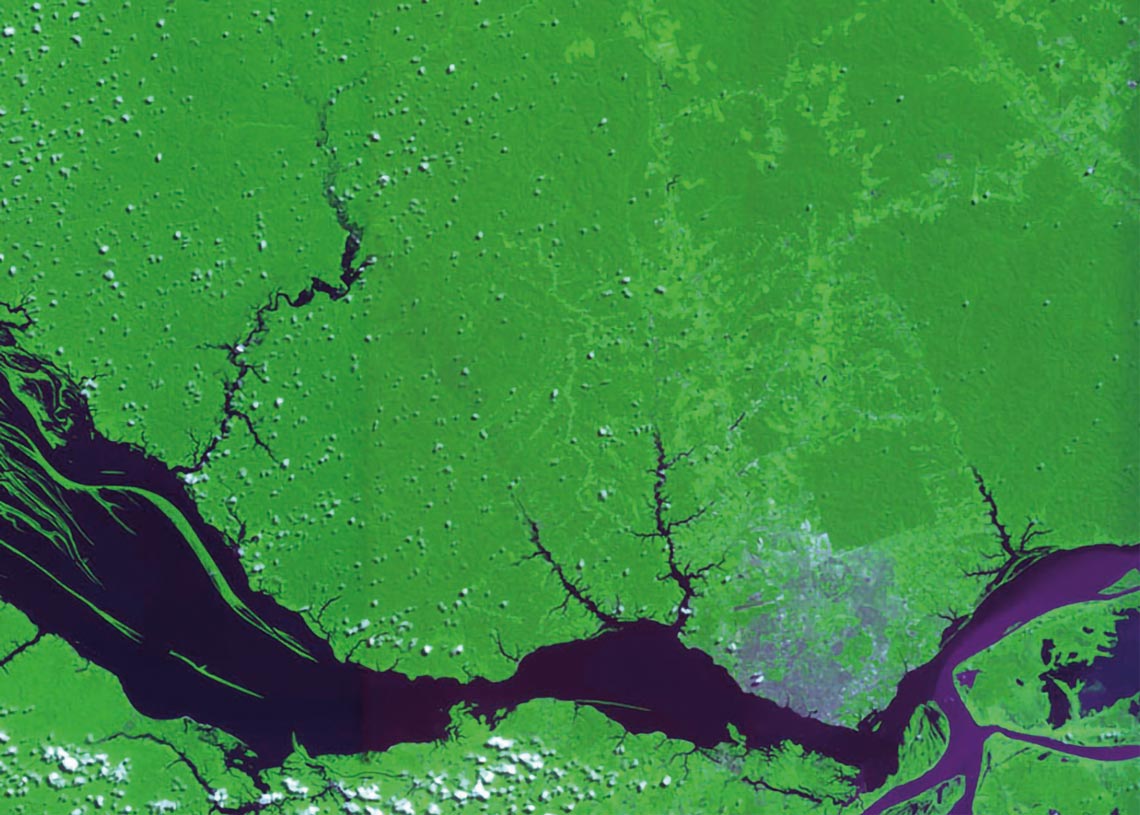

The MCTI also plans to resume the China–Brazil Earth Resources Satellite (CBERS) program, which has developed six remote-sensing satellites so far since 1990. According to CNPq chairman Ricardo Galvão, the resumed partnership with the Chinese should be agreed during an upcoming visit by President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva to Beijing.

Additionally, Minister Luciana Santos has emphasized the need to develop a new strategy for the semiconductor industry, which is heavily concentrated in Asian countries and was severely disrupted during the pandemic, leading to significant supply chain challenges in the global electronics and computer sectors. The minister has indicated plans to revitalize the Center of Excellence for Advanced Electronics Technology (CEITEC), a public corporation created in Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, in 2008. Although the company was originally intended to produce microchips, it was only successful in making low-complexity integrated circuits. In 2020 the government announced its decision to liquidate the company and sell its assets to the private sector. According to Luciana Santos, in its best year the company had generated revenue of R$7.8 million, but had sustained an average operating expense of R$80 million since its inception. Last year the Brazilian Audit Court (TCU) suspended the liquidation.

To discuss a future roadmap for science policy in Brazil, the new minister has convened a meeting of the National Conference on Science and Technology—the most recent edition was held in 2006. Future funding allocations will require careful consideration of new priorities and a balance between the needs of tens of thousands of individual research groups and larger-scale, strategic projects. In recent years, available funds have typically been spread out thinly across a large number of projects. “In its response to the pandemic, the MCTI selected projects for funding that were very dispersed and unable to build the momentum needed to make any meaningful contribution in tackling the health crisis,” says economist André Tortato Rauen from IPEA. “The projects that had the biggest impact were vaccine production programs run by the Brazilian Ministry of Health and the government of São Paulo.”

Besides resuming projects that never got off the drawing board, Fernanda De Negri believes discussions should look further into the future. “It is important to have a pipeline of enabling projects. The reinstated funding must come with more effectively designed policies, with more forward-looking strategies and goals,” she says. Brazilian science has clear strengths that can be leveraged in large-scale projects, she says. Climate change research would be a no-brainer, given the importance that the new administration attaches to the environment. This could lead to a robust pipeline of projects to develop climate mitigation technologies that can help to reduce emissions and decarbonize the economy, a research frontier that is important not only for Brazil but for the world as a whole,” she says. A new research agenda around the Amazon is another potential avenue to explore. “We need to invest in new technology to monitor deforestation. And developing sustainably produced non-timber forest products could help to create wealth and support new jobs in the Amazon. Most of the Amazon is in Brazil and we have institutions with the capabilities to conduct world-class research about rainforests.”

InpeA satellite image captured by CBERS: reactivating a partnership with ChinaInpe

She also mentions research on renewable fuels as a field in which Brazil has key strengths: “Funding could come from FNDCT, but there are also other sources that could be better leveraged. Regulated industries, such as oil and electric power, are required to invest a percentage of their revenues in R&D, and these funds could be used more effectively. However, notes De Negri, since funding for oilfield research is as volatile as global oil prices, researchers and laboratories often struggle to maintain long-term projects. “We need to reform regulations and create a fund to pool and manage resources for use in developing new sources of energy,” she suggests.

The acute funding crisis has masked some of the institutional progress that has been made, says André Rauen. “We’ve created a framework for technology procurement that provides companies with legal certainty, and we now have a modern regulatory toolkit for business relationships between the private sector, universities, and the government,” he says, referring to a federal government decree enacted in 2018 to regulate government contracts with private companies for R&D projects. “This legislation played a key role in building government partnerships with overseas companies to produce vaccines against the novel coronavirus,” he says.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESPThe Sirius synchrotron light source facility in CampinaLéo Ramos Chaves / Revista Pesquisa FAPESP

However, Rauen also acknowledges potential hurdles that could arise in applying the reinstated funding. Just as with doctoral programs, there could be a shortage of expert human resources to organize and manage large research projects. “If they are to be implemented effectively, our research systems will require more professionalized management. We have failed to train individuals with the needed in-depth knowledge about ecosystems involving industry, governments, and universities. The US has an abundance of professionals like these at agencies such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). We would need to create programs and a technological roadmap for the country, led by expert professionals.”

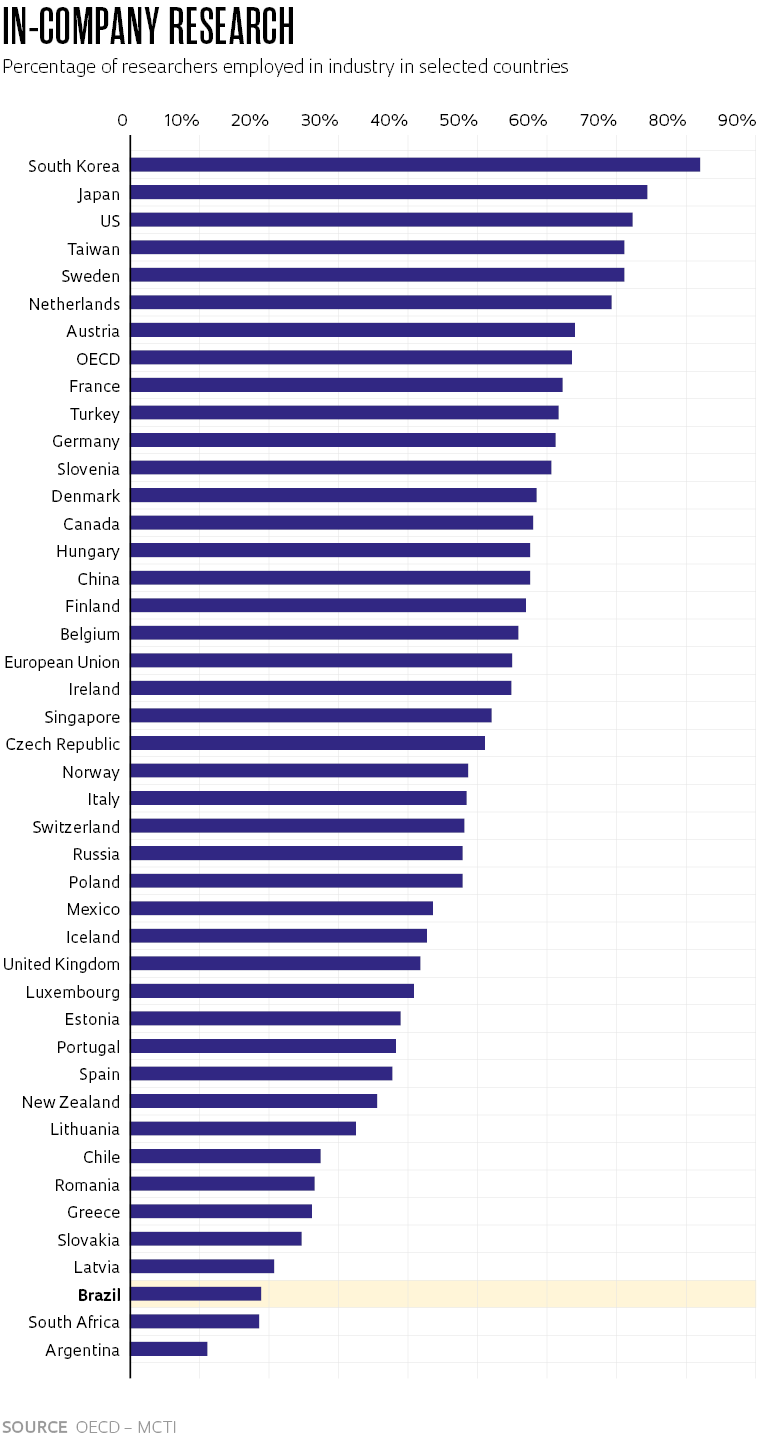

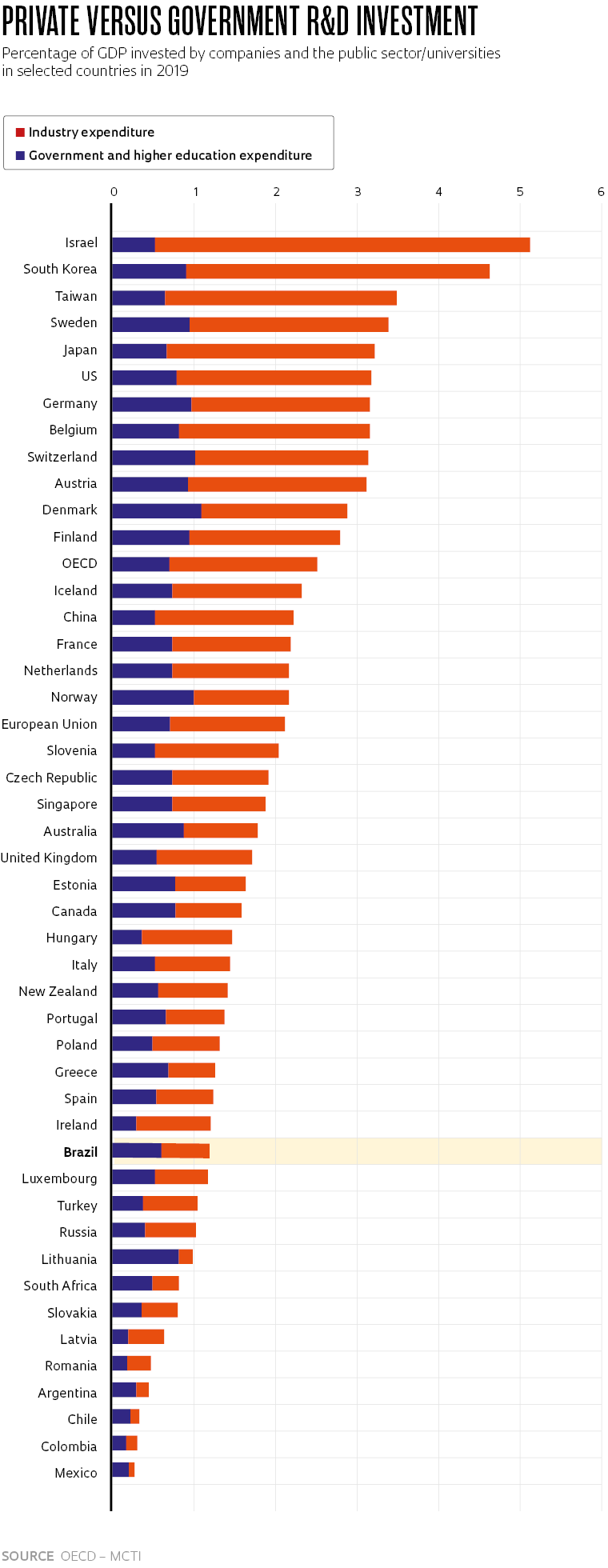

Physicist Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz believes that this is a unique opportunity for Brazil to rethink its science and technology system with a more ambitious mindset. “Can we build it back better than it was before?” he asked during an event in mid-December celebrating the 60th anniversary of FAPESP. “Going back in time and picking up where we left off in 2006 or 2007 would be a lost opportunity.” Brito Cruz, who served as science director at FAPESP from 2005 to 2020 and is currently senior vice president at Elsevier Research Networks in the UK, notes that public funds typically account for only a minority of research funding in most countries, and that Brazil needs to increase private spending in R&D and to boost the number of researchers working in industry, which is comparatively low. “Brazil’s science, technology, and innovation policy is built on the assumption that universities produce research, companies utilize it, and governments finance it. But in those countries that have successfully organized science and technology ecosystems that effectively benefit society, people, and the economy, things work differently,” he said in an interview with Pesquisa FAPESP. “In current research on quantum computing, companies like Google, Microsoft, and IBM are playing a role that is as important, if not more important, than universities.”

SENAI CETIQTEMBRAPII laboratory in Rio de Janeiro: impactful investmentSENAI CETIQT

He cited data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and MCTI indicating that the number of in-house researchers at companies in Brazil is well below the average for 44 other countries, with the country ranking at the bottom of the list. In Brazil, 59,000 researchers are currently working in industry—or 280 per million people. That number is six times higher in South Korea, and 10 times higher in the US.

He suggests exploring ways to encourage Brazilian companies to innovate to boost revenues and enter new markets. “Brazilian companies’ limited exposure to global markets and value chains is a counter-incentive to innovation. Complex tax laws are another barrier,” he said. “For instance, hiring a tax lawyer or accountant to cut through the complexity of Brazil’s tax regulations may seem like a safer bet than hiring a researcher for high-risk investment in a new product. Many of these ideas would come at no cost for the government. All it would take is effort and, of course, political determination,” he said.

Republish