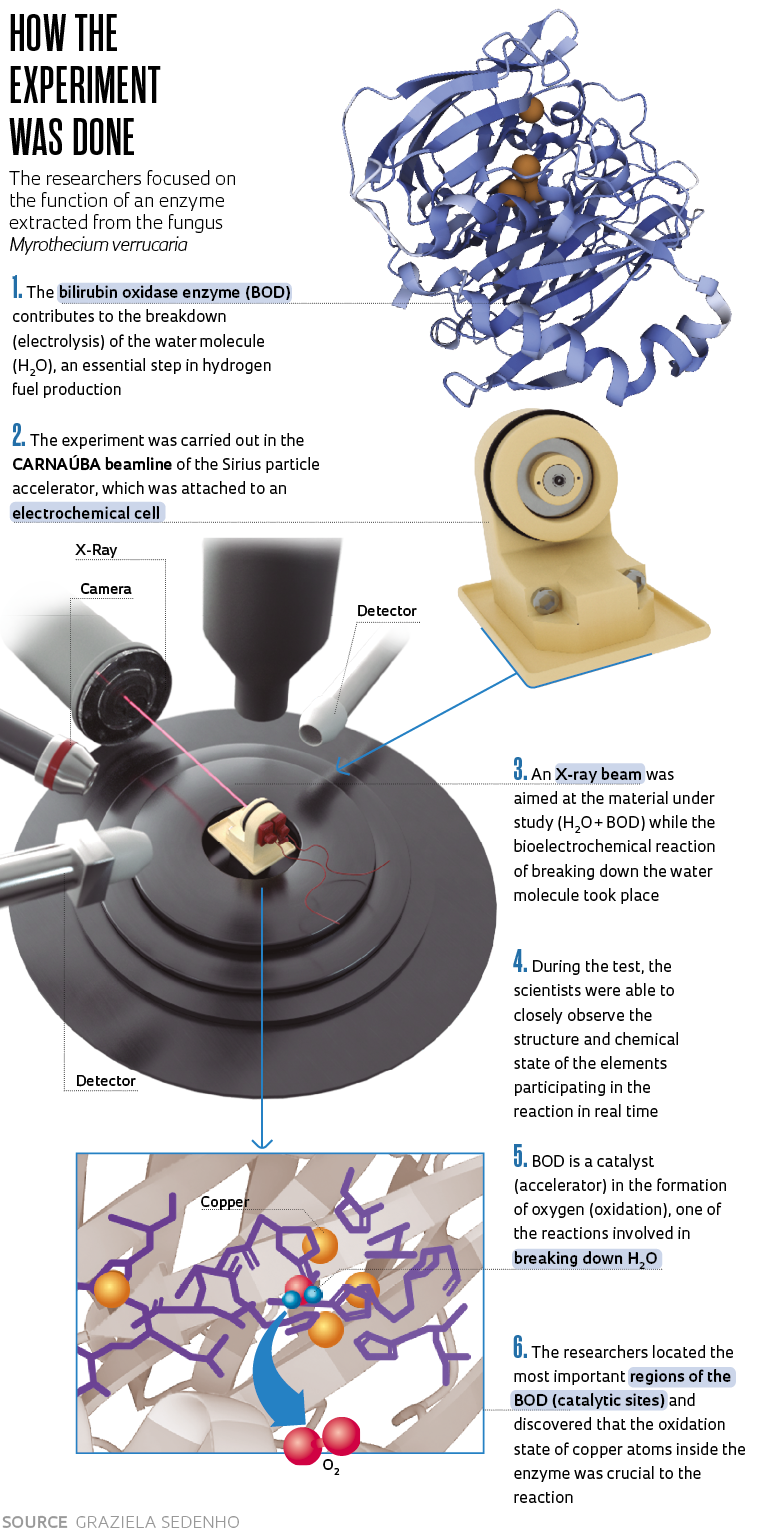

An experiment recently carried out at the Sirius synchrotron light source, based at the Brazilian Center for Research in Energy and Materials (CNPEM) in Campinas, São Paulo (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 269), showed how a certain biological catalyst made water (H2O) scission via electrolysis more efficient. This reaction, which was an electrochemical process that used electricity to decompose water into its constituent elements, is of great interest because, in addition to oxygen, it also provided hydrogen, which has been identified by many experts as the fuel of the future, since it generates no pollution (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 314).

“We discovered that when manipulated in the lab, some enzymes found in nature, including bilirubin oxidase [BOD], accelerated the water-breakdown reaction,” says chemist Frank Nelson Crespilho, a professor at the São Carlos Institute of Chemistry of the University of São Paulo (IQSC-USP) who led the study. “We did not know why this was happening. Thanks to new equipment developed especially for Sirius, we were able to determine how this enzyme, BOD, behaved during the water-oxidation process. We found that the copper atoms in the enzyme played important roles in the reaction.”

Crespilho believes scientists will be inspired by the part of the enzyme that accelerated the reaction. “It is interesting that we recognized the important regions of BOD because now synthetic chemists who produce new materials can copy that part of the enzyme and synthesize it in the lab. This will make the catalyst much more affordable and greatly expand its application range,” said the scientist. The catalysts currently used for the process generally contain noble metals, such as platinum and iridium, which are very expensive and thus make large-scale application unfeasible. An article describing the experiment was written by Crespilho’s team, which includes Graziela Sedenho, Rafael Colombo, Thiago Bertaglia, and Jessica Pacheco, and was published in the journal Advanced Energy Materials in October. Scientists from the Brazilian Synchrotron Light Laboratory (LNLS) also participated in the study.

Researchers around the world are searching for new water-oxidation catalysts

Bilirubin oxidase was extracted from the fungus Myrothecium verrucaria, which is commonly found in soils and on plants. When manipulated in the lab, it catalyzed the water breakdown reaction — something that does not occur spontaneously in nature. Inside the reactor, the enzyme acted more specifically in the formation of molecular oxygen, which is one of the two reactions needed to break down H2O molecules. The other is the formation of hydrogen, and the two occur concurrently. “For hydrogen formation, which takes place on one side of the reactor, everything is already better known. There are cheaper and more efficient catalysts. The water-oxidation reaction, however, is very slow, and scientists all over the world are seeking better catalysts for this,” explained Crespilho.

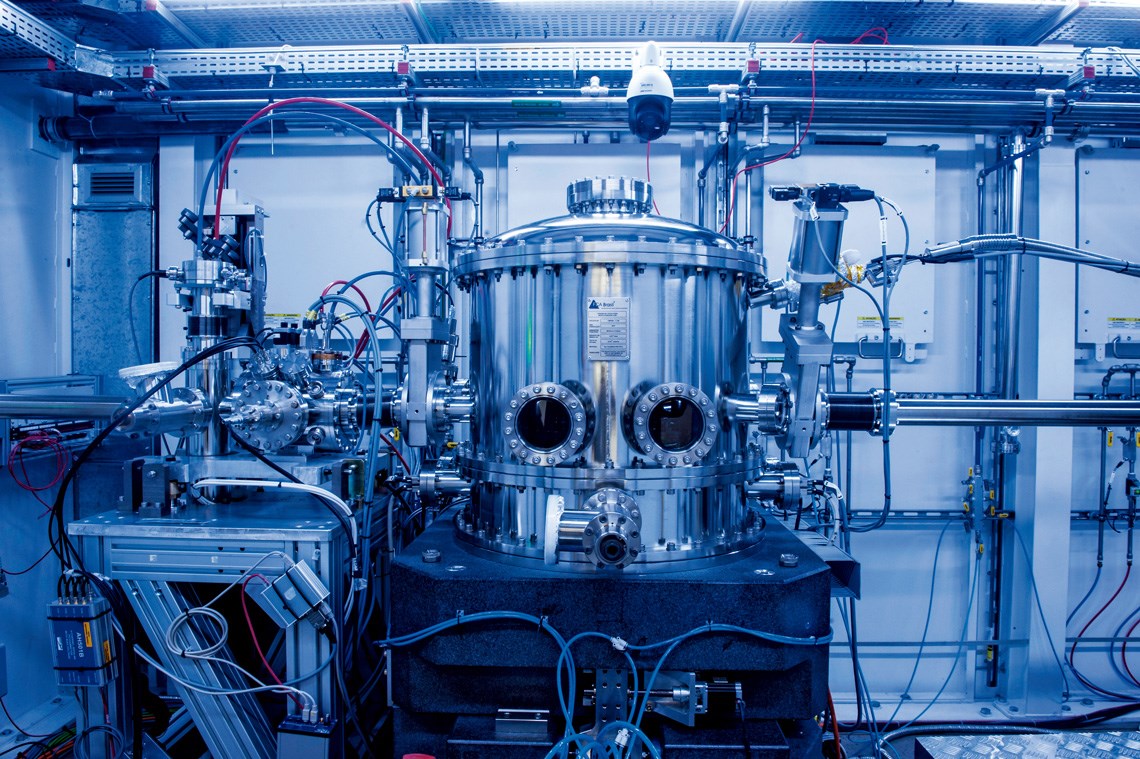

The researchers were able to observe the behavior of the enzyme during the bioelectrochemical reaction in such detail thanks to the cutting-edge infrastructure at Sirius. The team used the Tarumã experimental station of the CARNAÚBA beamline, which is still in the scientific commissioning phase, a process involving testing, technical development, routines, and experimental strategies.

“Various experiments and scientific topics are addressed in this phase, with the aim of demonstrating the potential of the beamline,” said physicist Helio Cesar Nogueira Tolentino, head of the Heterogeneous and Hierarchical Matter Division at LNLS. Of the 14 beamlines initially planned for Sirius, seven are already operational. Each operates with a different energy band using a proprietary technique. All seven are open to scientists from Brazil and abroad.

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP MagazineMonochromator: part of the CARNAÚBA beamline at Sirius, where the study was carried outLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FAPESP Magazine

Operating since late 2021, the Carnaúba beamline is the longest at Sirius. It was designed for X-ray absorption spectroscopy, which enables experiments with different materials on the nanometric scale. In addition to the powerful, superfocused beam of light, Crespilho’s group was also given access to a device recently developed by the LNLS team for biochemical studies.

“It is an electrochemical cell for in situ experiments. It is placed in front of the X-ray beam, which is focused on the material being studied at the moment the chemical reaction occurs. With this cell, we can also apply an electrical potential and measure the current or apply the current and measure the potential, which allows us to see how the material responds to these external stimuli, all while the chemical reaction is taking place,” explains Itamar Tomio Neckel, a physicist from the CARNAÚBA group at LNLS and the lead developer of the new electrochemical cell, a device small enough to fit in the palm of the hand.

The biggest challenge, according to the researcher, is to miniaturize everything, since the reactions have to take place in extremely limited physical spaces. Additionally, the conditions found in the laboratories of different users must be simulated. The CARNAÚBA beamline is 100 times smaller than a strand of hair and is known as an X-ray nanoprobe.