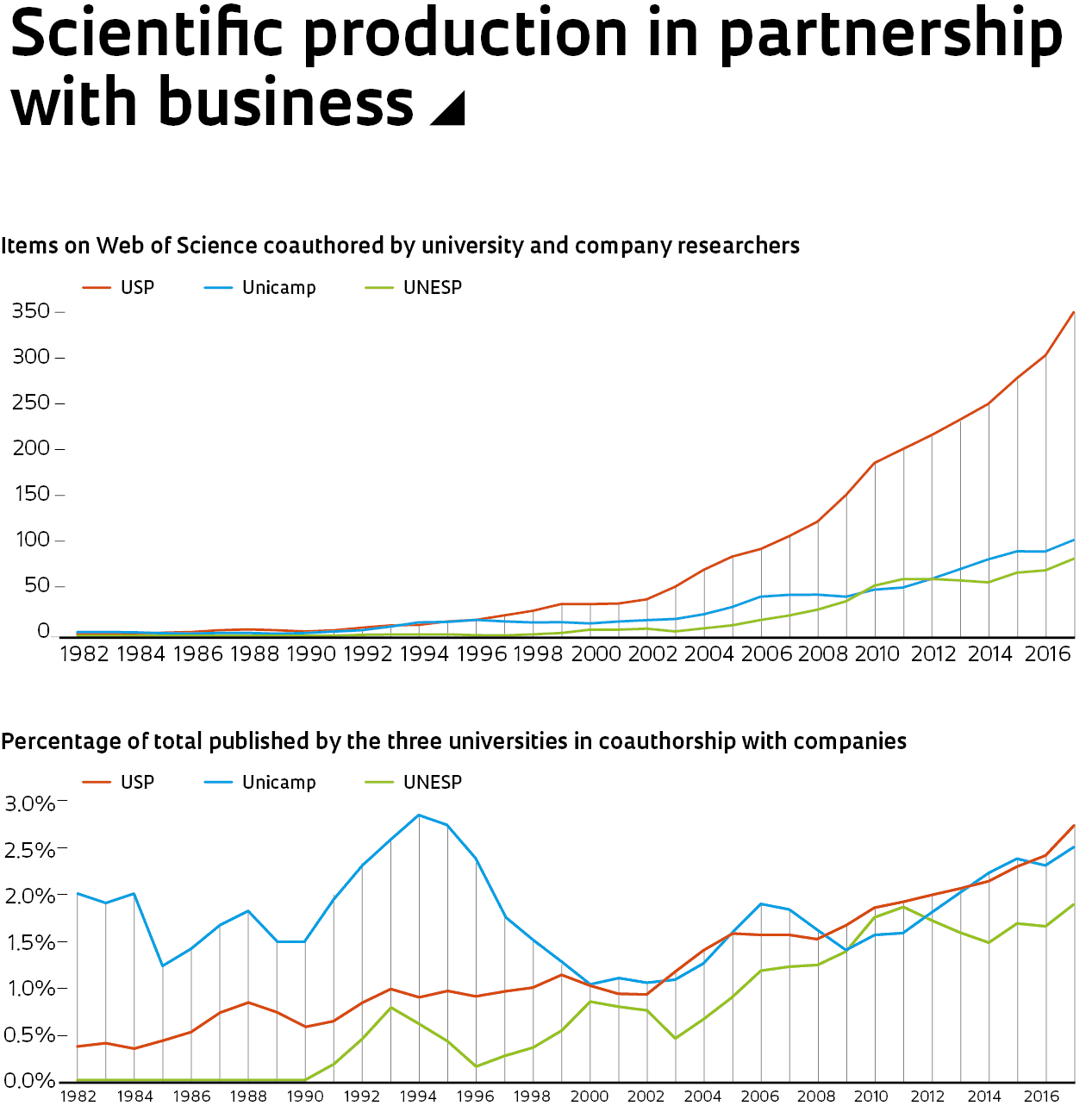

The last thirty years of financial autonomy at São Paulo’s three state universities parallel a period during which these schools vigorously protected the intellectual property generated by their researchers, increased collaboration with the industrial sector, and encouraged the formation of technology-based companies. During the 1980s, research collaborations were already frequent between business and the University of São Paulo (USP), University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and São Paulo State University (UNESP). However, in 1989, the universities were granted a guaranteed percentage of sales and services tax (ICMS) revenues; this new source of funding influenced their ability to produce innovation that had an economic impact on society. “An essential condition for a university to collaborate with business is to have the ability to do vigorous research. And financial autonomy was the key to increasing the scientific production of São Paulo state universities,” says physicist Marcos Nogueira Martins, director of the USP Innovation Agency, referring to the 16-fold increase in the number of scientific works published by the three institutions over the last three decades.

The data on science produced in partnership with business demonstrate this evolution. In 1989, just over 0.5% of USP’s scientific output indexed on the Web of Science database was coauthored by researchers associated with companies. By 2017, that percentage had risen to 2.7% (see table on page 37). The rate observed at UNICAMP increased from 1.5% to 2.5% over the same period, while UNESP went from zero in 1989 to close to 2% of articles being coauthored with company researchers in 2017. By comparison, the average in the United States was 2.8% between 2015 and 2017, while that of EU countries was less than 2.5%—with France and Germany exceeding 4%. Data on coauthoring between researchers from São Paulo universities and companies were published in May in the book Innovation in Brazil: Advancing development in the 21st century, in a chapter written by FAPESP’s scientific director, Carlos Henrique de Brito Cruz. Here, he addresses ways to evaluate this type of collaboration around the country. The chapter shows that in the case of USP and UNICAMP, companies’ participation in research funding exceeded the levels found at large foreign universities. Private research expenditures at UNICAMP were equal to approximately 13% of the contracts signed with public funding agencies in 2016, a rate slightly higher than USP’s 12%. This performance is on par with institutions such as Yale University or the University of California, San Francisco.

The list of large corporations that have research and development (R&D) partnerships with the state universities of São Paulo is extensive: Petrobras, BASF, Cargill, LG, Pirelli, and Natura are some of the universities’ most frequent collaborators. According to economist Renato Garcia, USP, UNICAMP, and UNESP were well positioned at the time companies began to look for outside support for their R&D efforts. “Until the 1990s, innovation at companies in Brazil was accomplished in-house and generated a set of products and processes capable of guaranteeing competitiveness. This has become insufficient over the last 15 years, and universities have become an advantageous conduit for supplying companies with knowledge and innovation,” explains Garcia, from the Institute of Economics at UNICAMP.

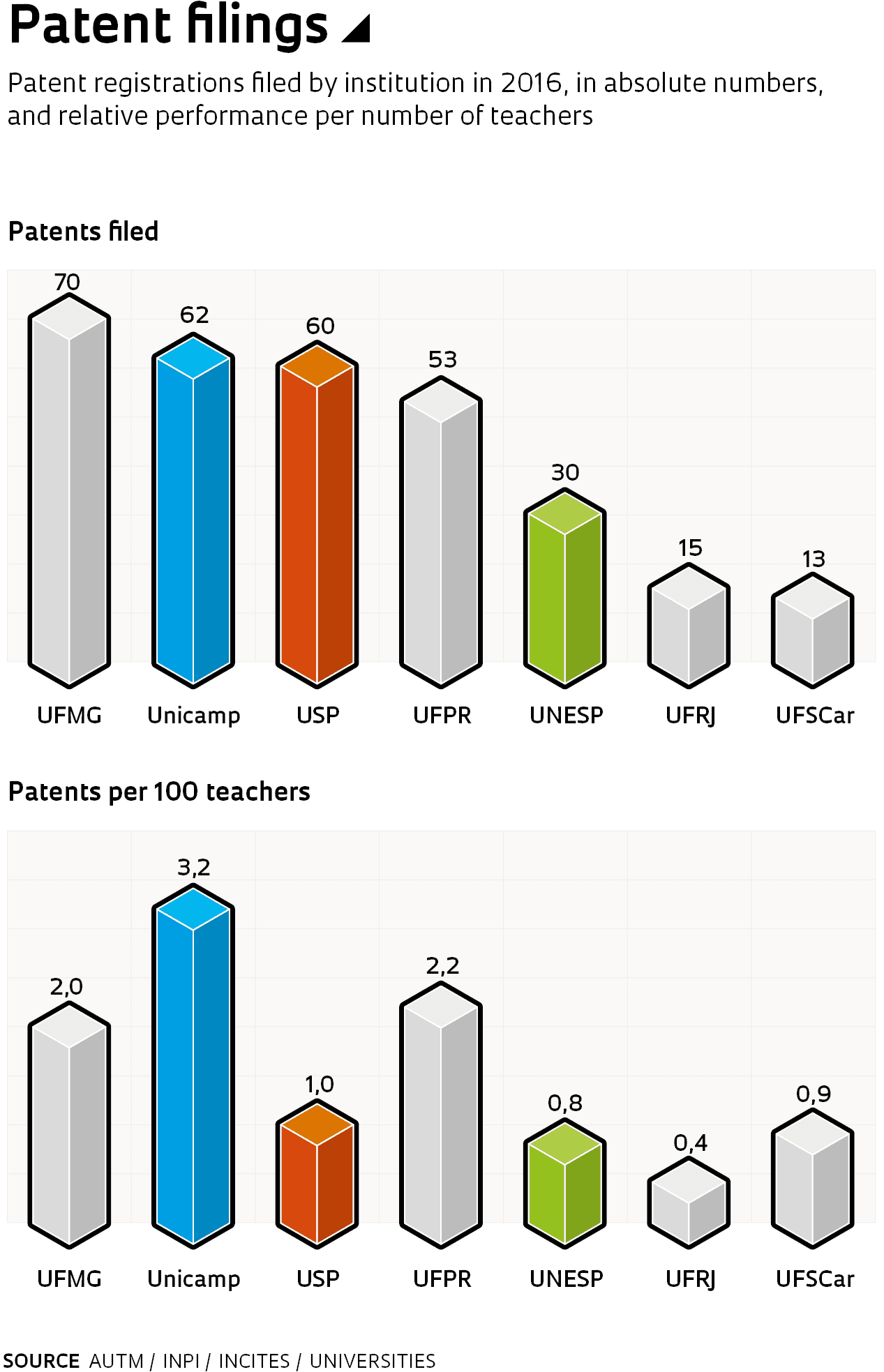

A study commissioned last year by the Brazilian Intellectual Property Association (ABPI) based on 4 million curricula vitae on the Lattes platform showed that out of a group of 15,600 Brazilian researchers who reported activity requiring intellectual property protection, more than 84.5% had high levels of academic productivity, with an average of 27 published articles. The three São Paulo state universities stand out in this study: among the 11,400 researchers and inventors across the country who had been granted patents, 7.3% worked at USP, 4% at UNICAMP, and 2.3% at UNESP.

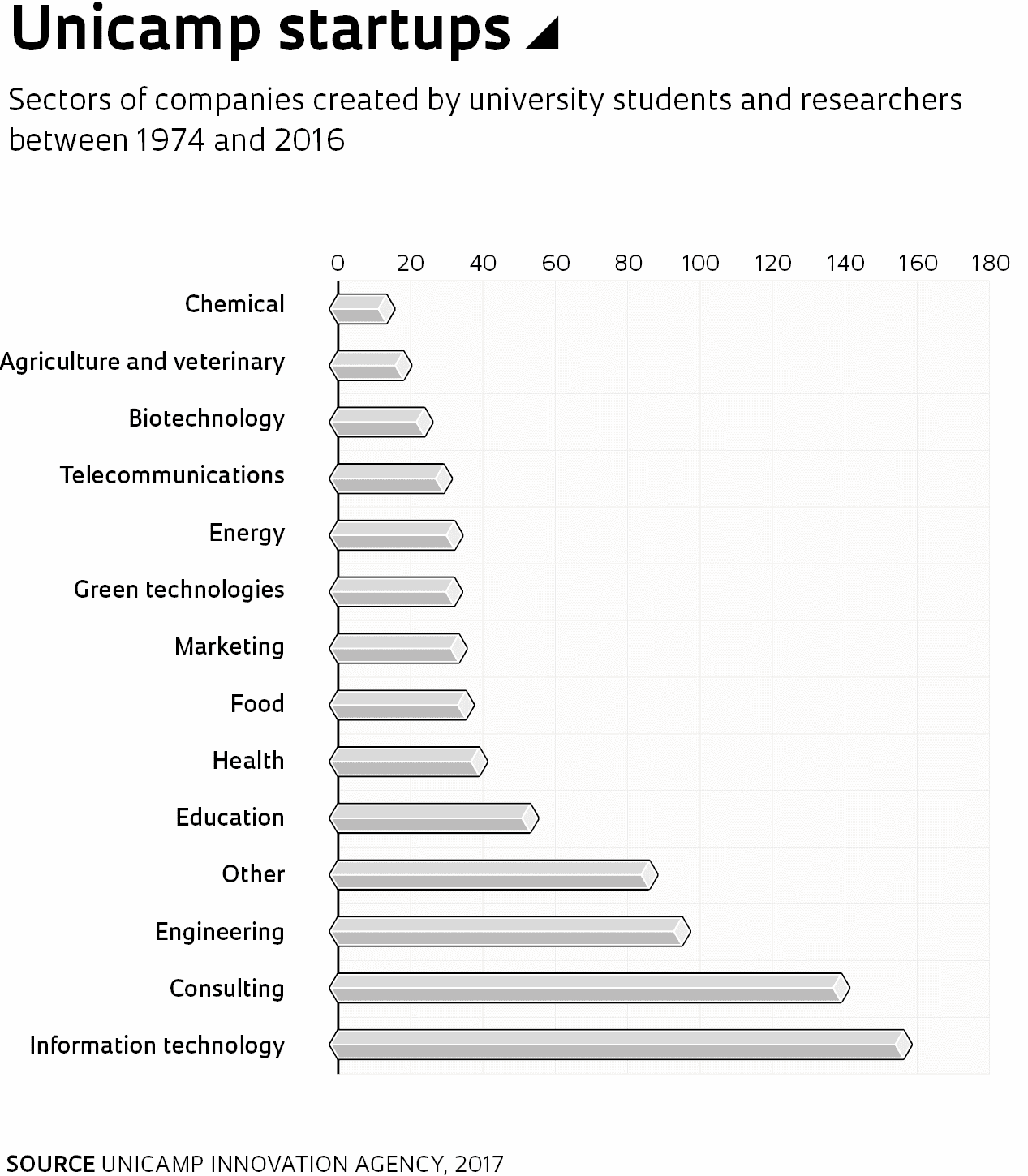

ver the past decade, the creation of innovation agencies at the three universities has helped to systematize intellectual property protection, highlight research results of interest to the private sector, and negotiate technology transfer contracts. UNICAMP launched its agency, Inova, in 2003, a year before the creation of the Innovation Law, which determined that all science and technology institutions in the country should develop Technological Innovation Centers (NIT) to manage their innovation policies. The university has always distinguished itself in Brazilian rankings for patent applications. In the latest list released by the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI), referring to 2017 numbers, UNICAMP was in first place in the overall ranking, with 77 patent filings. Only one company, CNH Industrial, appears in the list’s top ten, an elite club otherwise dominated by universities. With over 1,000 active patents, the university boasts excellent technology-transfer performance. In 2018, they had 115 active licensing agreements with various companies, which generated royalties of R$1.7 million for the university. They signed 22 new licensing agreements in 2018 alone.In the assessment of physicist Newton Frateschi, the agency’s director, the financial stability provided by autonomy has had a transformative effect on UNICAMP. “A fixed source of funds has enabled state universities to invest in planning. UNICAMP, which has always been interested in interacting with the industrial sector, is able to execute technology transfer strategies and enhance corporate access to their innovations,” he says. Guilherme Ary Plonski, scientific coordinator of the USP Center for Technology Policy And Management, also sees a relationship between autonomy and innovation, albeit an indirect one. “Compared with the trajectory of the federal universities, which did not achieve financial autonomy, I suspect that the performance of São Paulo’s state universities would have been weaker in terms of innovation if the 1989 legislation hadn’t been passed,” Plonski says. “The fact is that in the late 1980s there was a zeitgeist—an expression that designates the spirit of a time—favorable to both autonomy and innovation in São Paulo.”