After nearly ten years of planning, funding battles, team building, and successive refinements to laboratory techniques, a new approach to animal genetic improvement has finally yielded its first results: two Angus calves—a male and a female—from the same sire, with short, smooth, glossy coats, grazing and resting peacefully at EMBRAPA Dairy Cattle’s experimental farm. The pair are the first to be bred in an experiment to induce desirable traits in animals using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing.

The researchers’ goal was to introduce a genetic mutation that could produce short hair. They selected this trait because it is visible at birth, making it an immediate indicator of whether the experiment worked. This attribute could also enhance the animals’ heat tolerance compared with long-haired cattle.

In the lab, the EMBRAPA Dairy Cattle team, based in Juiz de Fora, Minas Gerais, created 16 embryos, which were implanted in late June 2024 into 16 cows that had been prepared to receive them. Six pregnancies progressed, though one ended before term. In the last week of April and the first week of March, five calves were born. Each showed a different degree of gene-editing efficiency, with incorporation rates ranging from 0% to 83%. Two calves were born with 74% and 83% genome editing, denoted by their short coats. Of the remaining three, two had long coats and no genome edits, while one, with an intermediate coat length, had 50% editing but died at 41 days from a bacterial infection.

“With precision breeding through gene editing, we can achieve in just a few years what nature would take decades to do,” says veterinarian Luiz Sérgio de Almeida Camargo, who is leading the project. Cattle brought from Portugal and Spain to Latin America and the Caribbean during colonization had long hair. Over time, some of their descendants developed natural mutations that produced a short coat. This trait enables the animals to regulate their body temperature more efficiently, reducing the stress caused by the intense heat and humidity of tropical and subtropical climates. Heat stress compromises animal welfare and leads to losses in both meat and milk production (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue n° 340).

Through crossbreeding and selection over multiple generations—the basis of conventional genetic improvement—developing new traits in livestock can take decades, far longer than in plants. “Fixing a trait in a cattle population can require five or more generations,” Camargo notes. He explains that precision breeding, when the gene controlling the trait is known, can lock in the desired characteristic in just two or three generations—without altering other traits as often happens with conventional methods.

Camargo recalls first discussing the potential of gene editing in cattle with colleagues in Brazil and abroad back in 2014. In 2022, he secured the project’s first funding through an innovation grant from the Brazilian Micro and Small Business Support Service (SEBRAE). Additional backing soon followed from the Minas Gerais State Research Foundation (FAPEMIG) and the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq).

He also partnered with the Brazilian Angus and Ultrablack Association, which provided the cows that carried the edited embryos. An article published in February 2022 in CABI Agriculture and Bioscience, and another in February 2023 in Animal Reproduction, outlined the EMBRAPA team’s approach to using CRISPR for cattle breeding. The paper presenting their most recent findings is still in preparation.

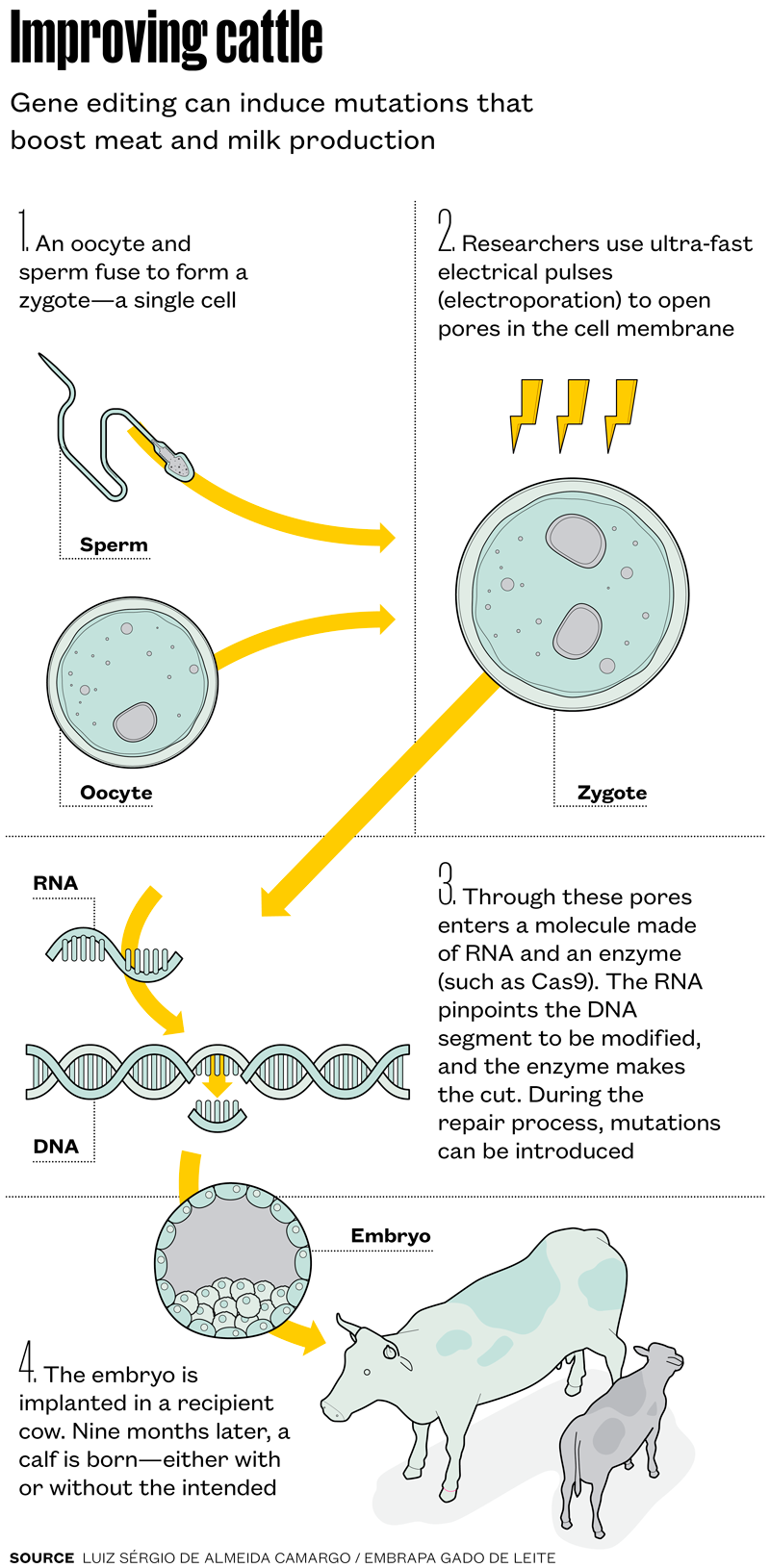

The genetic modification process builds on in vitro fertilization, with other methods layered in. “For nearly two years, we tested another approach for delivering edits into cells—microinjection—and an alternative gene-editing system, TALEN [transcription activator-like effector nucleases], but yields were consistently low,” Camargo says. Beginning in 2023, mutation rates tripled when the team combined CRISPR with a method called electroporation.

Electroporation uses high-voltage pulses lasting just microseconds to open temporary pores in the membranes of reproductive cells. Through these pores passes a molecule made of RNA and an enzyme that acts on DNA to create the intended genetic change (see infographic below).