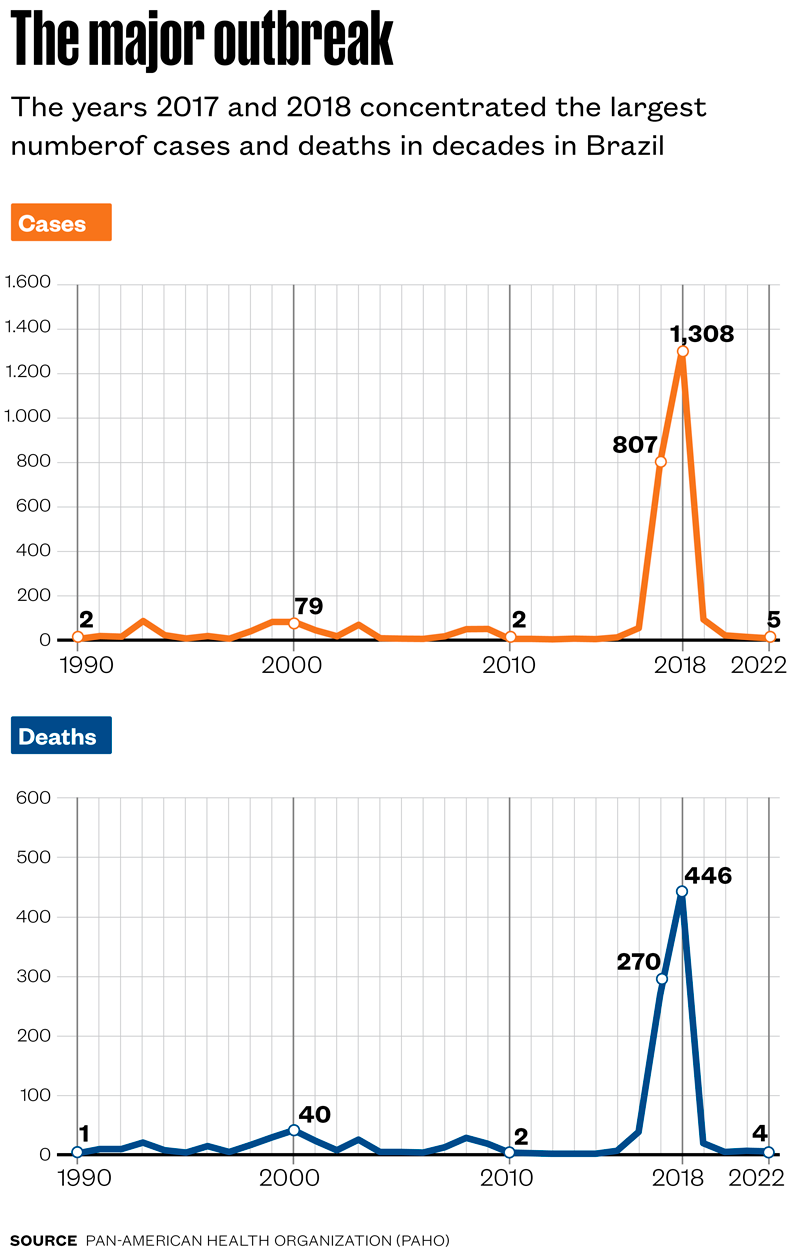

At the beginning of every year, new cases of yellow fever emerge in Brazil. One reason is that the period is favorable for the proliferation of mosquitoes that spread the virus to monkeys and humans in the forest and wooded areas close to cities. This has been the case for decades, and 2025 was no different. By mid-February, 12 people had been diagnosed with the infection in the state of São Paulo and eight had died—more than in the entire previous year. Although much lower than the outbreak that hit Southeast Brazil in 2017 and 2018, the current numbers were sufficient for the Ministry of Health to issue a notice advising travelers to get vaccinated before going to the areas with documented transmission. In turn, the State Health Department (SES) for São Paulo warned residents of the state to get vaccinated. “It is important that all those who have never been vaccinated against yellow fever do so,” said Tatiana Lang, director of the SES Epidemiological Surveillance Center, in a communication on February 14.

Endemic to forested areas of South America and Sub-Saharan Africa, yellow fever has a high mortality rate. Around 90% of those infected by the virus do not present symptoms or have mild symptoms, similar to those of a cold. However, in the other 10%, the symptoms are severe and up to half die. Analyzing the data of those who have died because of infection, especially during the last major outbreak, Brazilian researchers have begun identifying indicators of how the disease worsens and gaining a better understanding of the disorganization the virus causes in the defense system.

In the most recent study, published in December in the Journal of Medical Virology, the team of biologist and immunologist Helder Nakaya and immunologist and infectious disease specialist Esper Kallás, both from the University of São Paulo (USP), investigated the expression pattern of almost 25,000 genes in 79 people with confirmed yellow fever infection during the first months of 2018. The patients were hospitalized and treated in either the Emílio Ribas Institute of Infectious Diseases or in the Hospital das Clínicas (HC) of USP and monitored for up to two months. Twenty-six died and 53 recovered.

The expression profile of the genes was vastly different between the two groups and suggested that, in those who died, the immune system presented a more intense yet at the same time ineffective response. “The initial reaction to the infection was so exacerbated that it contributed towards the death of these individuals,” explains Nakaya, who is also a researcher at the Albert Einstein Israelite Institute for Teaching and Research (IIEPAE), in São Paulo.

One indicator of this potency was the activation of the gene pathway associated with the production of interferon, a chemical signal that is part of the first line of the antiviral response, known as innate immunity. Once the virus is injected into the body by the mosquito, a type of defense cell found in the skin—a dendritic cell—engulfs and digests it. Then, it initiates the synthesis and release of interferon, which acts on other cell types, inducing a response that limits the replication of the virus. At the same time, the expression profile of the genes of those who died likely showed a failure in the production of another chemical communicator, interleukin-1, which stimulates the proliferation and maturation of defense cells.

“The synthesis of interferon and other cytokines that promote inflammation is important, but when it is excessive and prolonged, as in severe cases of yellow fever, it leads to the exhaustion of the organs that produce defense cells,” explains immunologist Juarez Quaresma, of the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), who is researching the mechanisms of cellular death in yellow fever and did not participate in this study.

Besides producing interferon, dendritic cells perform another important role: they display pieces of the virus on their surface and, as a result, stimulate another type of defense cell—T lymphocytes, which are part of the adaptive response—to produce a specific response against the infectious agent. In the individuals who died from yellow fever, however, this presentation appears to be impaired, which may have contributed to the loss of effectiveness.

“Traditional methods of immune response analysis allow for the assessment of only a few blood proteins, providing a limited view of how the infection evolves. That is why we use a gene expression analysis technique, which provides access to the overall profile,” explains bioinformatics expert André Gonçalves, lead author of the study and a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oxford, in the UK.

“This study helps to understand how people’s immune systems respond to natural infection. Much of what was known about the immunopathogenesis of the disease in humans was based on the immune response to the vaccine, which simulates a milder infection. Today we have evidence that the response to infection and to the vaccine may differ,” says biomedical scientist Cássia Terrassani Silveira, coauthor of the study and a researcher on the team led by Kallás, who is also the director of the Butantan Institute.

Gene analysis also revealed another sign of a dysregulated and inefficient immune response in those who succumb to the virus. The gene expression profile of these individuals suggested that, during the initial stages of yellow fever, their bodies produced an innate defense cell more common in bacterial infections than in viral ones: neutrophils. More worryingly, the neutrophils were apparently immature.

James Gathany / CDCA mosquito of the genus Sabethes, one of the vectors of sylvatic yellow fever in South AmericaJames Gathany / CDC

Versatile and short-lived, neutrophils are among the first cells to migrate to the site of infection. Upon encountering a pathogen, typically a bacterium, the neutrophil engulfs it and releases a corrosive chemical bath at it. If the situation gets out of control, signals from the environment lead it to unwind its DNA and, in an explosive event, release it onto the invaders, soaked in toxic compounds. The role of this mechanism in viral infections is still under investigation.

Why, then, would the body produce neutrophils against the yellow fever virus? This phenomenon had, in fact, already been observed by Kallás and colleagues in the first study with patients from the Emílio Ribas Institute and HC, published in the Lancet Infectious Diseases in 2019. At the time, the researchers analyzed clinical and laboratory data from 76 individuals with yellow fever, of which 27 died. They looked for signs that could predict when a case would worsen, and the risk of death would increase. They identified 10 factors, including being over 45 years old, elevated markers of kidney and liver damage, and blood coagulation problems. However, two stood out: having an elevated concentration of the virus in the blood, something that had not been measured in yellow fever (this relationship does not matter in dengue, for example); and presenting a neutrophil count considered high for a viral infection, greater than 4,000 copies per milliliter.

“Two of the hypotheses that may explain the neutrophil count involve the occurrence of a highly elevated inflammatory response. It may be stimulating the production and release of neutrophils by the bone marrow and the passage of bacteria from the gastrointestinal tract to the blood due to a lesion in the intestinal lining,” explains biomedical scientist Mateus Thomazella from Kallás’s team, who is studying the latter phenomenon, known as bacterial translocation, and who recently identified signs of damage to intestinal cells in the blood, with data submitted for publication.

The intestines may just be one more organ damaged in severe yellow fever. The virus primarily replicates in the cells of the kidneys and especially the liver, but tissue and organ analyses from autopsies have revealed more widespread damage. Examining the organs of 73 people who died from yellow fever, the group led by pathologist Amaro Duarte Neto, from USP, identified heart lesions in over 90% of them. The data were presented in an article published in 2023 in the journal eBioMedicine. The following year, in the same publication, the team led by physician Ester Sabino, also from USP, demonstrated a mechanism by which the virus damages the endothelium, the internal lining of the blood vessels.

Years earlier, Quaresma, from UFPA, had already observed—while analyzing tissue from 10 people who had died of yellow fever in other Brazilian states—that the cytokines produced in response to the virus altered the behavior of the endothelium, facilitating the entry of defense cells into the lung tissue, causing damage, bleeding, and mucus buildup, as described in an article in the journal Viruses in 2022. “With the worsening of the infection, the lungs are the last organs to be affected and lead to death,” affirms the immunologist.

The story above was published with the title “A devastating virus” in issue in issue 349 of march/2025.

Projects

1. Viral metagenomics of dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika viruses: Monitor, explain, and predict spatial-temporal transmission and distribution in Brazil (nº 16/01735-2); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Ester Cerdeira Sabino (USP); Investment R$445,187.99.

2. Systems biology of long non-coding RNA (nº 12/19278-6); Grant Mechanism Young Investigator Award; Principal Investigator Helder Takashi Imoto Nakaya (USP); Investment R$1,298,032.85.

3. Integrative biology applied to human health (nº 18/14933-2); Grant Mechanism Young Investigator Award; Principal Investigator Helder Takashi Imoto Nakaya (IIEPAE); Investment R$2,326,694.25.

4. Network statistics: Theory, methods, and applications (nº 18/21934-5); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator André Fujita (USP); Investment R$1,595,955.04.

5. CPDI – Center for Research into Inflammatory Diseases (nº 13/08216-2); Grant Mechanism Research, Innovation, and Dissemination Centers (RIDCs); Principal Investigator Fernando de Queiroz Cunha (FMRP-USP); Investment R$72,926,585.03.

6. Investigation of neutrophilia in patients with acute yellow fever (nº 19/13713-1); Grant Mechanism Doctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Esper George Kallás (USP); Beneficiary Mateu Vailant Thomazella; Investment R$148,324.57

7. Implementation of an in vitro model to assess vascular permeability for studies on the pathogenesis of hemorrhagic dengue and screening of compounds with therapeutic potential (nº 13/01690-0); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Ester Cerdeira Sabino (USP); Investment R$230,535.39.

8. Assessment of endothelial permeability for studies on dengue pathogenesis and screening of compounds with therapeutic potential (nº 13/01702-9); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship; Supervisor Ester Cerdeira Sabino (USP); Beneficiary Francielle Tramontini Gomes de Sousa; Investment R$525,578.45.

Scientific articles

GONÇALVES, A. N. A. et al. Systems immunology approaches to understanding immune responses in acute infection of yellow fever patients. Journal of Medical Virology. Dec. 5, 2024.

KALLAS, E. G. et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with yellow fever:

An observational cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. May 16, 2019.

GIUGNI, R. F. et al. Understanding yellow fever-associated myocardial injury: An autopsy study. eBioMedicine. Oct. 2023.

DE SOUSA, F. T. G. et al. Yellow fever disease severity and endothelial dysfunction are associated with elevated serum levels of viral NS1 protein and syndecan-1. eBioMedicine. Nov. 2024.

VASCONCELOS, D. B. et al. New insights into the mechanism of immune-mediated tissue injury in yellow fever: The role of immunopathological and endothelial alterations in the human lung parenchyma. Viruses. Oct. 27, 2022.

Republish