Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa Fapesp

Chamon: plans are to launch a second Brazilian astronaut into space, possibly within the decadeLéo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FapespAfter a career of almost 40 years with the Brazilian National Institute for Space Research (INPE), Marco Antonio Chamon, a trained electrical engineer with a master’s and PhD in space technology, was appointed president of the Brazilian Space Agency (AEB)—the organization managing Brazil’s space program—in July 2023.

Chamon admits that Brazil’s space exploration efforts have lagged in the last 20 years, especially compared to China’s and India’s rapid ascent. Yet he also has positive developments to share for the coming years, including the launch of two suborbital rockets—or rockets that enter space and then return to the surface—later this year for microgravity research. Other developments include the construction of two new satellites featuring novel technologies, in a collaboration with China and Argentina.

Successful construction of suborbital rockets is an important first step in the development Small Lift Launch Vehicles (SLLV), a key goal of Brazil’s space program. “The maiden launch of the VLM-1, a solid-propellant rocket, is scheduled for 2026,” says Chamon.

In this video interview, the AEB’s new president also outlines plans to expand the use of satellite data by private businesses and discusses Brazil’s role in the Artemis mission, NASA’s Moon exploration program. Lastly, he explores future collaborations with other space agencies, some of which were agreed during a scientific conference in Europe in the second half of 2023.

You recently attended the International Congress of Aeronautics in Azerbaijan. What insights did you bring back with you?

We had a week packed with meetings , engaging with all the major space agencies—American, Chinese, Russian, and European. I was especially happy to see that all parties showed interest in collaboration with Brazil. Two main topics dominated my discussions. The first was reinstating Brazil into the international arena. Although our space program is smaller than some, we’ve launched several satellites and have international agreements for scientific and technological cooperation. Secondly, we discussed our role as an experienced partner, serving as a gateway for nations entering space exploration without well-established programs. For countries like Colombia or Rwanda, it’s easier to team up with Brazil than with NASA [the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration]. I sensed that we’re seen as a trustworthy partner. The credibility of our space program was further highlighted by an invitation to the Space Economy Leaders Meeting [SELM] at the G20 Summit, held in July in India [the G20 brings together the 19 largest global economies, along with the European Union and the African Union]. In 2024, we are set to host the inaugural United Nations Space Economy Conference.

In Azerbaijan, was there interest shown in using the Alcântara Space Center (CEA) in Maranhão for launches?

Development of Alcântara as an international rocket launch facility is not progressing at the pace we had hoped for. However, we need to remember that the original goal when the base was created 40 years ago was developing a rocket launch site to have our own space capabilities. A few years ago, the Brazilian Air Force [FAB] determined that leveraging the CEA’s strategic geographical position for launches by other countries could be co-beneficial. This hadn’t been considered before because, two decades ago, only a handful of countries had space programs. Many more countries do today, though only a few have the capabilities to independently launch satellites and rockets. In 2023, South Korean aerospace and defense company Innospace conducted a suborbital test flight at Alcântara, which they selected specifically for its favorable geographical position. Proximity to the Equator results in fuel savings. Innospace is scheduled to carry out another operation in 2024, likely a commercial launch. Similarly, Canadian company C6 Launch Systems plans to run an engine test in Alcântara in 2024 before it decides on whether to use the base in the future. The level of interest in Alcântara is anticipated to rise following the inaugural commercial launch.

What is Brazil’s current standing in the global space scene?

Twenty years ago, Brazil, China, and India were in comparable positions. However, while China and India have since made substantial progress, we have lagged behind, moving at a slower pace than we probably should have. Periods of limited investment have hampered progress, with some components of the program coming to a complete halt. In recent years, we have barely managed to maintain the facilities at Alcântara, with no further expansions or upgrades. When we launched the Amazonia-1 satellite in February 2021, we had to use an Indian-made rocket for the launch, at a cost of nearly US$26 million [see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 300]. Encouragingly, there are signs that things will improve as the Brazilian government continues to attach increasing importance to the space program. While the AEB’s budget has remained flat, it has been substantially supplemented by other sources of funding, including calls for proposals in the industrial sector to develop satellites and small launch vehicles.

What is the agency’s current budget?

Our budget for 2024 is R$102 million, very close to the 2023 figure. For comparison, NASA’s budget is around US$20 billion, or approximately R$100 billion—nearly 1,000 times larger. NASA’s budget translates to about US$60 per American citizen per year, and the French Space Agency (CNES) has a budget of €35 per capita per year. Ours corresponds to R$0.64. The Brazilian government has sought additional sources to boost investments in the space program, potentially increasing our budget for next year four-fold. This would inject needed momentum into the program. I hope funding continues to grow in the coming years.

What are your plans for 2024?

If the schedule holds, we should launch our VS-50 rocket this year. The VS-50 is a suborbital vehicle, meaning it doesn’t go into outer space. It follows a parabolic trajectory, crossing the theoretical boundary between Earth’s atmosphere and outer space [100 kilometers above sea level] and then returning. Although it can’t place satellites in orbit, during a few minutes of flight it creates a microgravity environment that is useful for a variety of scientific experiments. Additionally, if successful, it will be an important step toward building Small Lift Launch Vehicles (SLLV), as both use the same engine (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 311). In 2024 we also anticipate the launch of another suborbital rocket, the VS-30, at the Barreira do Inferno Launch Center in Rio Grande do Norte. This launch will be important for microgravity research. A suborbital flight provides a microgravity environment for a few minutes, ideal for scientific studies of physical, chemical, and biological phenomena such as crystal growth, heating or cooling of materials, and stress in biological cultures. It can provide a better understanding of these phenomena in microgravity conditions to improve processes developed back on Earth. This valuable research can make the case to the public and the government that our program is yielding meaningful results.

If the launch of the VS-50 is successful, what would the next steps be in your SLLV program?

If the VS-50’s maiden flight is a success, it will be followed by a second flight in 2025, as several tests are needed to ensure safe operation. Preparations for the SLLV will also begin concurrently. The inaugural launch of the VLM-1 is slated for 2026, featuring a solid-propellant rocket. The VLM-X, an upgraded version of our launcher, incorporates two solid-propellant engines inherited from the VS-50 and a third liquid-propellant engine currently in development at the IAE [the Brazilian Aeronautics and Space Institute]. There is currently no specified timeframe for the launch of this rocket.

What are your priorities as head of AEB?

First and foremost, I need to reassure my colleagues in the private sector that the space program is a State program. While I enjoy some independence, there are established goals, guidelines, and commitments that will be maintained. From a technological standpoint, we have two separate focus areas: upstream and downstream. The first relates to infrastructure, including satellite control bases, data capture, and large antennas. This is quite expensive to build, requiring government funding and the involvement of institutions like INPE and DCTA [Department of Aerospace Science and Technology, an arm of the Brazilian Air Force], the agencies that contract with companies to build satellites and rockets. The second focus area, which I intend to expand on, is exploiting the satellite data. Private companies could use the data to offer value-added services to farms, businesses, and the government. Our satellite data is publicly available, which makes things easier for new entrants from the private sector. What we plan to do is to use the data to create products that can be commercially exploited by private businesses. For instance, meteorological and soil moisture data can be processed and turned into products and services for agricultural customers. In Brazil, the most immediately obvious application for satellite data is deforestation monitoring, but the images need to be processed and interpreted. This is currently handled at INPE, but I would like to see the private sector involved as well, creating opportunities for new businesses and jobs.

We are looking to collaborate with NASA in space farming, or the cultivation of crops for food in space

What steps have you taken to increase private-sector involvement in this area?

I’ve had talks with the directors of several science parks to mobilize small firms primarily, which tend to be more nimble and innovative. While these new business opportunities are expected to become self-sustaining over time, they may initially require government support. We are currently working to develop new approaches to support. The Brazilian Aerospace Industry Association (AIAB), for instance, has more members in the upstream than in the downstream sector. Our goal is to drive growth in both areas—maintaining capabilities to build equipment while amplifying the use of satellite data. Expanding international cooperation agreements is another priority. Under a long-standing agreement with China, we are currently collaborating on the development of another satellite, CBERS-6, as part of the China–Brazil Earth Resources Satellite program. A more recent agreement with Argentina has led to the Sabia-Mar satellite program.

In what ways are the two different?

They are two different types of satellites. CBERS-6 also differs from the predecessors we have developed with China over almost four decades. This program, which began nearly 40 years ago, primarily involved optical satellites designed for capturing images, each weighing around 2 metric tons [t]. In contrast, CBERS-6 is a radar satellite that will capture different types of imagery using what we refer to as synthetic aperture radar technology. This technology provides the advantage that it can see through clouds, a capability that optical satellites lack. CBERS-6 will also be a smaller satellite, weighing approximately 700 kilograms [kg]. It will be mounted on the Multi-Mission Platform [PMM], a versatile structure developed by INPE in the 2000s and previously used to build the Amazonia-1 satellite. While we are keen to develop our own radar hardware, it is currently being supplied by China. The launch date is set, optimistically, for 2028.

And what about Sabia-Mar?

The launch is scheduled for 2026. This satellite will provide information on the water quality of coastal and continental water bodies; Brazil has watersheds, hydroelectric dams and reservoirs that are large enough to be visible from satellites. Captured data will show, for instance, the amount of chlorophyll in the water, which is useful in assessing carbon absorption and climate change. There are actually two separate satellites being developed—one by Argentina and the other by us—each weighing approximately 700 kg. The concept is that the two satellites will work together to gather twice the amount of information. Another difference is that we will develop the satellite entirely, while in the program with China, we are responsible for half of the development. We can also leverage our existing Multi-Mission Platform for Sabia-Mar. This platform is currently 60% complete.

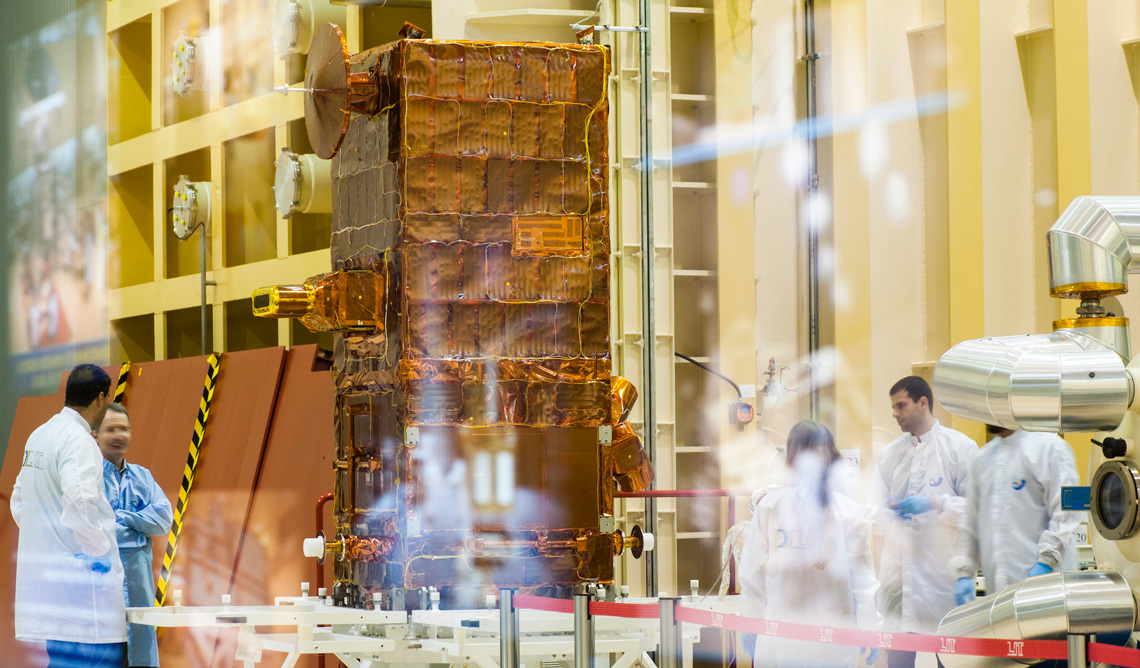

Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa Fapesp

Engineers assembling the Amazonia-1 satellite, launched in 2021Léo Ramos Chaves / Pesquisa FapespWhen you became president of AEB, you mentioned that the Brazilian space program could help reduce social inequality. In what ways?

We have been exploring multiple avenues. One approach is to reduce the concentration of aerospace companies in São José dos Campos [SP] and stimulate new businesses or expansion into other regions. We’re developing collaborations with universities, science parks, trade associations, and state and municipal governments to develop local aerospace clusters. These locations could be used to build small satellites. While large satellites require equally large-scale infrastructure, developing small satellites can be an opportunity to create new businesses and train specialized personnel. Tracking deforestation using satellite data is one example of a service that can be provided by local private companies. They would of course need a solid business plan, but the upfront investment would be small—primarily computers, software, and personnel. And with our open data policy, satellite imagery and climate data are either free or low-cost. These services could stimulate local economies and alleviate regional inequalities.

What is the status of Brazil’s participation in Artemis? Are we sending another Brazilian astronaut to space or to the Moon?

Our goal in the Artemis program [NASA’s crewed spaceflight program] is not specifically to send a Brazilian astronaut to the Moon, although we certainly plan to send another astronaut into space, perhaps within this decade. And while this would grab headlines, it is not the most important aspect of the Brazilian space program. Its primary objective, from the outset, has been to benefit society. Like other countries, we have only signed the more general part of the Artemis Accords, a set of principles regarding the peaceful use of outer space, sustainable space exploration, data exchange, etc. We are pursuing two major goals within Artemis. The first is to conduct scientific research using the Moon as a platform. ITA [the Brazilian Air Force Institute of Technology] is working with INPE to design a small satellite, weighing 10 or 20 kg, to be placed in lunar orbit. It will take scientific measurements to determine how solar radiation behaves and impinges on the Moon and, ultimately, Earth itself. The second area we intend to exploit—and NASA has already shown interest in exploiting with us—is space farming, or growing crops for food in space. We’ve already signed an agreement with EMBRAPA [the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation], and we are now working to raise the necessary funding.

In what ways is your background in research helping you in your current executive role?

I’ve found that my almost 40 years at INPE have made it easier to navigate the space sector, which is still relatively small in Brazil but is expanding. When I was appointed president of AEB last year, I already knew many of the people at INPE, ITA, the Air Force, aerospace companies, and universities. While not everyone agrees with me, and I don’t agree with everyone, our discussions are always strictly technical and never personal, and we are able to keep our relationships both amicable and professional. Overall, we have been able to have meaningful conversations and find a common language and shared objectives, which helps to streamline progress.