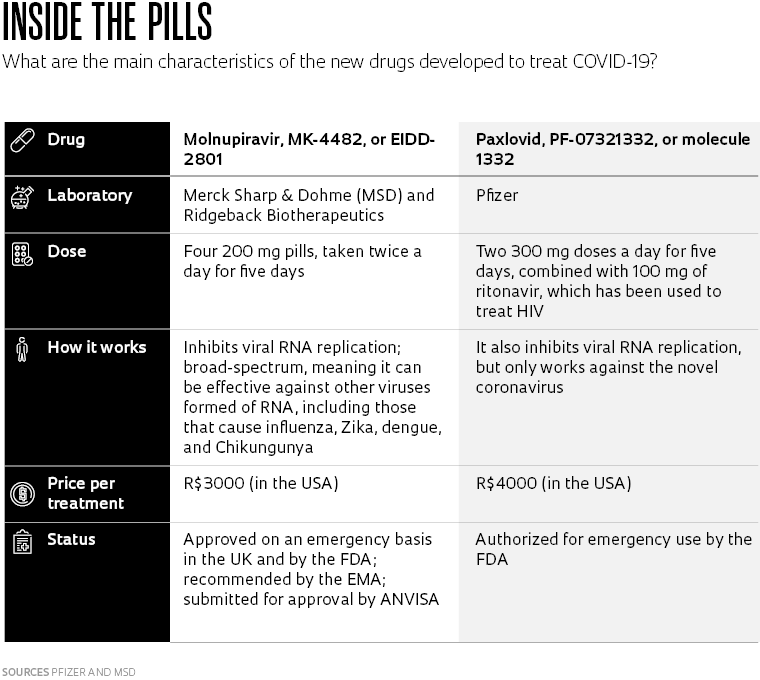

Two years after COVID-19 emerged in China, the world continues to deal with the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. With nearly 9 billion vaccine doses administered worldwide—most in high-income nations—more than 47% of the global population is now fully vaccinated against the disease. Although this is not enough to stop the spread of the virus—especially when new variants like Omicron appear to evade the vaccine to some extent—advances are also being made on other fronts. The most encouraging news concerns two antiviral drugs, the first to be administered orally, that have shown promising clinical results: paxlovid, made by Pfizer, and molnupiravir, made by Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) in partnership with biotechnology company Ridgeback Biotherapeutics.

The UK approved molnupiravir on an emergency basis in early November under the trade name Lavregio. It has also been authorized by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and has been recommended by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for patients who do not require oxygen or who are not at risk of developing a severe form of the disease.

According to a global study by MSD that involved 1,433 participants in 170 countries—including Brazil—the drug reduced hospitalizations and deaths from COVID-19 by 30% in symptomatic patients with at least one risk factor (obesity, diabetes, severe heart disease, or aged over 60).

Of the 709 volunteers who received molnupiravir, also called MK-4482 or EIDD-2801, 48 (6.8%) were hospitalized. Of the 699 participants who took a placebo, 68 (9.7%) were hospitalized. Nine deaths were reported in the placebo group versus one among those taking the antiviral drug. Treatment consisted of 800 milligrams (mg) of molnupiravir administered twice a day for five days.

Pfizer’s drug, meanwhile, was authorized by the FDA on December 22 for emergency use in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2. The clinical trial carried out by the pharmaceutical company was originally designed to include 3,000 volunteers from 21 countries, including Brazil. After promising early results, the sample size was reduced to 774 people.

When given to patients with at least one risk factor prior to the third day of symptoms, the drug decreased hospitalizations and deaths by 89% compared to the control group. Less than 1% of patients who took the drug (3 people out of 389) were hospitalized and none died, while 7% of those who received the placebo were hospitalized or died (27 out of 385, with 7 deaths). The patients were given two 300 mg doses of paxlovid per day, plus 100 mg of ritonavir, for five days. The latter is used to treat HIV and helps increase the amount of time the antiviral remains active in the body.

AFP PHOTO / PFIZERProduction of paxlovid in Pfizer’s laboratory in Freiburg, GermanyAFP PHOTO / PFIZER

Different strategies

According to the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, 264 antiviral drugs are currently under development worldwide to tackle SARS-CoV-2, in addition to 233 vaccines and 364 other treatments, totaling 861 medical approaches to contain the pandemic. These vaccine and drug candidates fight the virus in different ways.

“The mechanism used by molnupiravir is broad-spectrum, meaning that it can act on several viruses whose genetics are formed of RNA [viruses can also be made of DNA]. This is the case with the arboviruses responsible for dengue, Chikungunya, and Zika, as well as the virus that causes flu,” explains Marina Della Negra, MSD’s medical director in Brazil.

Della Negra says that molnupiravir, originally developed by scientists at Emory University in Atlanta, USA, was intended for use against other viruses, such as the flu, until the beginning of 2020. Ridgeback Biotherapeutics then bought molnupiravir, and the COVID-19 pandemic changed the course of its development, focusing on SARS-CoV-2. Clinical trials began in April, and Ridgeback partnered with MSD the following month.

The results helped to explain the key qualities of the new drug. “The mechanism of action inhibits the replication of any viral RNA. Basically, it introduces particles analogous to the nucleosides [basic RNA or DNA units] that form the virus’s genetic code into the body. This generates mutations and causes what we call a viral error catastrophe, where the RNA becomes unviable and the virus stops replicating,” explains Della Negra. It was this that led to a drug initially designed to combat the virus that causes influenza becoming yet another weapon in the arsenal against SARS-CoV-2.

The fact that molnupiravir genetically alters the novel coronavirus also raised a concern: could the drug cause genetic mutations in carriers of the virus that lead to undesirable side effects, such as the development of cancer? According to Della Negra, studies showed a low risk of genotoxicity in live test subjects, such as mice and other rodents.

“There is a theoretical risk, but preliminary investigations in animals by MSD did not show any increased risk of mutations. But broader and longer-term studies are needed,” says Eduardo Medeiros, an infectious disease specialist from the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) and scientific director at the São Paulo Society of Infectious Diseases (SPI).