EDUARDO CESARIn a 15-minute documentary made by Walter Lima Júnior in 2004, at one point Thomaz Farkas, 82 years old, tells that he ought to have been born in Brazil, because in 1924 his parents were already living over here. Without many resources, when the moment of the birth drew close, they asked Farkas’s maternal grandmother for financial assistance; she was “a bit of a skinflint” and on top of that didn’t like her son-in-law very much. The result was that she sent only one ticket by sea for her daughter, and Farkas was born in Hungary. It was only when he was 5 years old that he was to arrive in São Paulo – to remain in this city for all of his life.

EDUARDO CESARIn a 15-minute documentary made by Walter Lima Júnior in 2004, at one point Thomaz Farkas, 82 years old, tells that he ought to have been born in Brazil, because in 1924 his parents were already living over here. Without many resources, when the moment of the birth drew close, they asked Farkas’s maternal grandmother for financial assistance; she was “a bit of a skinflint” and on top of that didn’t like her son-in-law very much. The result was that she sent only one ticket by sea for her daughter, and Farkas was born in Hungary. It was only when he was 5 years old that he was to arrive in São Paulo – to remain in this city for all of his life.

Years later, Farkas was to become a fundamental figure in the history of the Brazilian cinema, with his zeal for producing or co-producing, with his own resources, almost two score documentaries of different lengths, which had the intention of showing the Brazilians the various and truest faces of Brazil. This bunch of films that is today once again in circulation, mainly on the cable TV channels, is inside an original enterprise that justifiably took the name of Farkas Caravan. What was that? From São Paulo, small teams led by different filmmakers would set out, eager to explore the country. They would set off bound for the North, the Northeast, the South and the Center-West, they would burrow into the Southeast, São Paulo itself, in an impressive desire to reveal where we are from, after all.

But Thomaz Farkas was not only the producer of so many films. A photographer of fine images, concerned with the supposedly classical sameness of the framing that used to dominate Brazilian photography in the 1940’s, for this reason a renovator of language, he went to teach photojournalism for a few decades at the Communication School of the University of São Paulo (USP). And now that he was at USP, he saw himself obliged to do a doctorate. In his thesis, which will be transformed into a book by Cosac Naify, he dealt with the production of documentaries in Brazil. Graduated in engineering from USP’s Polytechnic, he did very little with this degree, because after all he had to handle his work as a businessman: Farkas was the owner of Fotoptica, a chain of photography shops.

In the following interview, he talks a bit and with much humor, almost always, about these various facets. And he offers as a present to the readers of Pesquisa FAPESP the marvelous photos of his authorship that are in the four central pages of the space dedicated to the interview. Oh, incidentally: in the film by Walter Lima Júnior, the title of which is Thomaz Farkas, Brazilian, he confesses that he “would have chosen Bahia” had he been given the right to choose a place to be born.

EDUARDO CESARDid you read the interview with Fernando Birri [in Pesquisa FAPESP issue 127]? He makes a reference to you at the beginning…

EDUARDO CESARDid you read the interview with Fernando Birri [in Pesquisa FAPESP issue 127]? He makes a reference to you at the beginning…

It’s because we are very good friends, and since he came to Brazil for the first time, it was to help us. Some Argentineans came here having been put to flight. Maurício Berú, who was also a filmmaker, arrive and phoned me from the airport, “Look, we are here, me, my wife and two children”.

It was you who went to fetch them.

Yes, because you know how it is, the guy who escapes for political reasons comes in the clothes he is wearing. I know about this, this refugee business… My family is Jewish, I left Hungary in 1930.

But did your father came as an exile as well?

No, daddy came out of work. He was a draftsman at an arms factory in Hungary. Hungary lost the war, the factory closed, and he left Hungary. He went to several places. My uncle, his brother, already know Brazil. He went to fetch daddy and sent him over here, to found Fotoptica, in 1920. I think that in those days, in the sector, there was only Lutz Ferrando, if I am not mistaken.

Conrado Wessel did not exist yet?

The factory? Yes, it did. I have an excellent letter from Conrado. He was a marvelous person. Well, daddy came, founded Fotoptica, then went back to Hungary, married my mother and I was born in 1924. And I came here in 1930. Ah, I want to tell you about my first filming. Of Pixinguinha (a famous musician and songwriter) in 1954, at the inauguration of the Ibirapuera park. I read in the newspaper that Pixinguinha was going to play with his band, and in those days there was little Brazilian regional music, there was a lot of American and European music… I saw that, picked up my 16 millimeter, silent camera and a tripod.

It was a camera imported from the United States.

A Kodak. A very good camera. I have it to this date, kept safe. They played and danced at the same time, all of them, and it was a marvelous spectacle. I filmed I think eight minutes, there were two 100-foot rolls, four minutes each, and what was left of film I filmed at home, my children in the bath, family stuff. That was 52 years ago. The film got lost there in my office. And one day, four or five years ago, I began to tidy things up a bit and, suddenly, I found a small film. What was it? It was Pixinguinha in the negative! The film was silent. I revealed it and thought it was a marvel. It was seven, eight minutes long. Then I amplified it to 35 millimeters and went to the Moreira Salles Institute to see whether they could discover the music they were playing. They did discover it, OK. And now, one or two years ago, I spoke to Ricardo Dias, who is my friend – he made the film Fé [Faith] -, and he made the film with me. It comes to ten minutes. It’s a marvel, with them playing and dancing. You see the knife on the plate, you see the pandeiro ( a kind of tambourine) … And I commemorated that.

Before we talk about photography, let’s talk about your experience with documentaries.

We did an exploratory trip through the country, Geraldo [Sarno], Paulo Rufino and I, in 1967 and 1968. We went by jeep. I had some ideas, they did as well, and the first one was to film the revolution of Julião in Pernambuco.

The Peasant Leagues of Francisco Julião.

Yes, but it so happens that [Eduardo] Coutinho was there in those days, and the repression came down on top of him. We decided not to go, and as I had a piece of equipment that had just arrived, we began to think about what we were going to do. We went up to Ceará, Maranhão, Paraíba… We went to look. And Sérgio Muniz, later on, also went to look. I mean, there were people traveling over various regions with the idea of showing Brazil to the Brazilians. I though that that would be the biggest revolution that we could make, because Brazilians did not know Brazil, there was no television to show everything. Then I thought that showing the people of Rio Grande do Sul to the people of São Paulo, to the people from the Northeast, and vice-versa, was a novelty that could possibly set off a revolution, at least in the mind. I took the first four films to TV Cultura to see if they wanted to show them, but as it was the time of the dictatorship, someone said to me, “Look, there’s a lot of misery”. And then I explained, “That’s not misery, that is how people live”. And he said, “Yes, but in these days of dictatorship, they are going to think that I am wanting to show something ugly…” So nothing was shown on the television in those days.

How were these journeys done, inside the Northeast, afterwards, a bit over the South etc.?

I had a C-14 [a Chevrolet pickup truck]. Before that, I had a jeep, and all the filming was done using these cars. Sérgio Muniz went to the South.

The exploratory journeys happens and afterwards you would go back and make the documentaries?

Some films had already been made before, starting in 1964. We made this exploratory trip and afterwards we met, with the question: “What are we going to do?” I had in my hands a study done by a geography teacher saying what there was in each place in Brazil, what was cultivated etc. At that moment, Glauber [Rocha] asked for Geraldo Sarno to come here, because he was getting in the way up there. You know, Glauber was from Bahia. Geraldo is a Bahian from Poções, everything was from Bahia… Geraldo came to join the group. At the beginning of the 1960’s, Professor [Vilanovas] Artigas said to me, “Look, there are some folks there who are tinkering with cinema, don’t you want to join them?” It was Capô [Maurice Capovilla] and Vlado [Vladimir Herzog], who had come from the school, I think.

They had come from the Santa Fé Cinema School. They had been through there before 1963, with Fernando Birri.

Precisely. So they brought one experience, Geraldo brought another experience, and he suggested Paulo Gil [Soares], who was a marvelous person, and the plan was born: get the C-14, the equipment I had, and get on board. One cinematographer, one director, and me driving the car. The people were few, but very competent, beginning to film the projects that we had done.

And your role was that of a sort of coordinator, a general producer of this project?

I was a producer. I had to arrange for the money, I had to pay them, I had to buy material, have them developed.

And how were the funds raised at that moment?

They weren’t raised, it was me paying it in directly.

So you were the great financier of the Brazilian documentary.

I had that possibility, at Fotoptica. I had some money that I earned, a monthly allowance, in short, and I had saved. Also, they weren’t today’s salaries, they were normal salaries. Today, the prices are sky high. But things started to move. For example, I had a plan to go to Crato ( a city in the state of Ceará). We went, and we filmed what there was of interest. Afterwards, we went to a nearby city, where we discovered a host of other things: a cassava meal place, a bomb factory… What there was in the region, we filmed.

THOMAZ FARKASThe idea was to film how Brazilians from each place live, what there real production was.

THOMAZ FARKASThe idea was to film how Brazilians from each place live, what there real production was.

How they lived. So we make, instead of 10, 20 films, 30 films. In all, counting those that were made before and after these journeys, there are 39 films, between 1964 and 1980. There is also a full length film, there are films produced in São Paulo. Viramundo [Wounds in Brazilian Society], for example, was made here, in 1965. We made films in the South, like Andiamo In’mérica [Let’s Go to America] [1977-78], which is about Italian immigrants. In short, we did heaps of things.

The majority of the films were of 10 to 15 minutes?

Let’s say from 10 to 40 minutes. Some would be full length. Sérgio Muniz filmed Andiamo In’mérica as a program that Embrafilme wanted to finance to show on the TV. But he saw that he had material for two 40-minute films. He also made Rastejador, s.m. [Tracker, masculine noun][1970], which is about a guy who used to help to find tracks of bandits in the Caatinga. At the same time, he did Beste [Crossbow] [1970], about this same tracker making a crossbow to kill little animals. A crossbow is a small bow and arrow. The editing was at my house, in Pacaembu. I had everything: an editing machine, a camera and a tape recorder.

And all the documentaries were filmed in 16 millimeters, or already in 35?

The majority was is 16 millimeters. But there was also some in 35 millimeter, like Memória do cangaço [Memories of the Cangaço][1965], by Paulo Gil. We used to show them in the university circuit, the parallel circuit. I remember when Joris Ivens came here; he was a Dutch documentarian, marvelous, he brought Heaven and Earth, a film that he had made in Vietnam. I projected this film at home, someone got up and said, “This is communist stuff”, and left. And I ended up at the police department, arrested, because of that and other nonsense.

It was back on the 1970’s that he made an agreement with the French filmmaker Pierre Kast, wasn’t it?

I don’t remember. I have here the film called Les carnets brésiliens [The Brazilian Notebooks].

Is it something that joined up bits from Viramundo, Memórias do cangaço, Nossa escola de samba [Our Samba School] [1965] and Subterrâneos do futebol [The Soccer Underground][1970]?

No, that was Brasil verdade [True Brazil]. Pierre came because I had a friend who was a friend of Glauber, Claude Antoine. Well, when Pierre Kast wanted to do a series here for French television, Claude Antoine brought the French producer, I joined him, a each of us went in with some money to finance this Carnets brésiliens, which is a marvel, narrated in French, show on French television.

And in this Carnets brésiliens are many pieces of documentaries joined together?

It’s a film about the general culture of Brazil, something more urban. In fact, Pierre worked hard, he did everything on his own. For example: the film about Vinicius de Morais, which has now come out in DVD, has two passages that are in Carnets: the little group from the shantytown dancing, and the colored footage from Vinicius’s house.

What was your connection like with the Brazilian Association of Documentarians, created in 1975, if I’m not mistaken?

The Brazilian documentarians were us. I mean, before us there was León Hirszman, who made a film about Brasília.

Even so, was it your wish to create a documentary center in São Paulo?

Look, we were a group. I wasn’t going to found anything, nor was I going to make a group, but there was the gang that was working with me in those days.

What was it like for you to reconcile the production of a documentary and also to take care of Fotoptica?

In Fotoptica, I had partners, and they would run the company. I would pass by there, go back home to take care of something, to take care of the development. Once in a while, I would go and have a look at how the folks were filming. Photography, in those days, was a bit abandoned. The other day, I went to the house of my daughter Beatriz, to see the filed wreckage of my life, and I saw the negatives of the photographs taken at the filming. There are many of them.

Photos of scenes?

Photos of scenes and settings. Birri and Edgardo Pallero, Argentineans, had got the photo documentary craze badly. I mean, they would take a photograph of what they wanted to do, set it up, and work with photography before filming, because it was expensive to film and to photograph was cheaper. Then the group I talked about was formed and I helped to finance the documentaries at that moment, because I was able to. Today I would no longer be able to.

But I am a witness that your zeal in supporting the production of documentaries in Brazil that seemed important to you went far beyond that. In 1978, on the eve of the 1st Brazilian Amnesty Congress, Agnaldo Siri Azevedo, Rino Marconi and Timo Andrade (further on, Roman Stulbach) were looking for funds to make viable the project for a short film, subsequently baptized as Anistia 1978 d.C. [Amnesty 1978 AD], about the assassination by the dictatorship, in 1973, of two militants from Popular Action: Gildo Macedo Lacerda and José Carlos Novaes da Matta Machado. Incidentally, in 2005, they, along with three other students from the institution in those days, in a fine homage by the Federal University of Minas Gerais. Well, the fact is that the group went to see you, and you simply gave them all the negatives to make the filming viable.

I didn’t even remember that. But in our area we were very united politically. In a way, I think that our political vision was just one, it was a vision of transforming things, improving things. I have that to this date. I am a raving optimist.

THOMAZ FARKASWere you connected with the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), the Big Party?

THOMAZ FARKASWere you connected with the Brazilian Communist Party (PCB), the Big Party?

No, I was a sympathizer. I used to contribute to those things that I understood to be important, but I wasn’t linked to the party. To belong to the party, you had to have discipline, study Marx, Engels. I was never connected with any party.

So it was a question of contributing to productions that seemed to you to carry the idea of transformation?

That is what it was. I gave for a film about Lula the images that I had of his first political rallies. To film today on film is very expensive, but in a way everything has changed, because it’s done digitally. So that is a very interesting revolution. We used to film 3 meters to use 1. Today, with digital filming, you film 100, 150 meters, for 1. I mean, in the old days, the thinking on research used to be done in the mind. Today, you film and afterwards see what has turned out, which is very different. It may be excellent and it may be nonsense. Modern photography is the same thing in digital. You take a thousand photos to use 10 or 20. In the old days, you would use almost everything, because it was expensive to develop and to make copies.

That was a very serious problem for the first decades of Brazilian cinema, wasn’t it?

Buying films, developing them, afterwards there was the crew, which was already expensive, the camera was rented. Anyway, I thing that, for me, the main thing was always this thing here, that I am going to show you. This here was the most important thing…

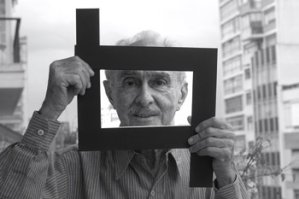

Ah, the mask.

… that I had because, as a photographer, and as a person, I always see things like this [Farkas looks through the cardboard frame, literally framing what he is looking at].

Then the notion of framing that you developed comes into the scene…

People see what they frame, you understand? What interests me is what I see, I don’t not see everything. Although my vision goes from one side to the other, I am always concentrating. And even with the photograph after enlargement, I cut a bit off, I decide: I’m not going to enlarge everything. So, for me, photography is vision. Reality is not in photography.

But this comprehension of yours about framing in photography, which comes from the 1940’s, had a strong influence, decades later, on the teaching of photography schools.

I think it did. But each one, each filmmaker, has his way of seeing. Mine was like that

What was the problem with photography done prior to the 1940’s?

It was a copy out of its time of old, classical things. I fled from that.

What cameras do you keep on using?

I had a Nikon, but it got heavy and my doctor said, “If you carry on working with that camera, you’ll become a hunchback”. I bought a Leica, which is nice and light, but I still have the Rolleiflex.

Do you use a digital camera?

No. I have so much material accumulated to be organized that there’s no time.

Let’s talk about your life as a teacher: did you go to USP’s Communication and Arts School (ECA) to teach photojournalism?

When I saw that the ECA was going to be formed, I thought, “That interests me, because I do cinema, and they may want a teacher of cinema”. I went there, I looked up Rudá [de Andrade], who was a friend of mine, and Professor [José] Marques de Melo, and I offered myself, “Who knows, you may need me in the cinema department”. But that department already had a photography professor, and Rudá proposed that I should teach photojournalism. So for many years I taught the folks from the journalism school to take some photographs, because the reporter often goes into the field alone, without any photographer with him, and in this way he could take the photo himself. I had very good pupils, some of them marvelous. But with the professors it was more difficult.

What was the problem with the professors?

A lot of envy, a lot of disputes, and I always wanted to stay clear of that.

And why did you do a doctorate?

I had to do it to stay in the school. The theme was films. And things ended up being very interesting, because the first bench proposed was not accepted by the director of the school. Paulo Emílio Salles Gomes and Maria Isaura Pereira de Queiroz were part of it.

What was the argument used against the bench?

They invented that Paulo Emílio and Maria Isaura were fresh doctors. My supervisor, Flávio Motta, who was a genius, did a marvelous reply to the director, the rector, tearing the allegations into shreds. But I was only able to defend my thesis a long time after. I wrote it in 1972, and I defended it in 1974, 1975, I think, with another bench. Now the Cosac Naify publishing house wants to publish the book, because it is the first thesis about documentaries made in Brazil. I hope the book comes out while I am alive.

We have here in the photo appendix to the thesis Paulo Gil with the crew at Taperoá, and photographer Afonso Beato, today with many awards…

He worked with us. He is a marvelous photographer. And here are Lauro Escorel, Geraldo Sarno, Edgardo Pallero, who came from Santa Fé and stayed here in Brazil. Incidentally, I always tell the same story: he stayed because he had a particular way of dealing with the people here. Fernando Birri, for example, used to schedule a meeting with filmmakers at 10 o’clock, in some place in Rio. He would go, the filmmakers wouldn’t turn up. He would get mad. Pallero would say 10 o’clock, the filmmakers weren’t there, he would go to the beach and find everyone there. That was the big difference between the two. Pallero, who is now dead, was a great teacher.

You said that you never worked with photojournalism and were going to say something about your work as a photographer.

The thing is that I am a borderline photographer – I am not an amateur, but nor am I a professional, I don’t make my living from this. I’d like to, but I don’t.

eduardo cesarHave you never earned money with your photographic work?

eduardo cesarHave you never earned money with your photographic work?

No, nor with cinema. Rather, a little bit of money is now coming in with cinema. TV Senado [Senate TV] bought a batch of over 20 films, Canal Brasil [Brazil Channel] bought some… And, although I have the rights, I distribute a small part to all the directors. They all receive a part corresponding to the minutage. I don’t owe anything to anyone.

How was the proposal that César Lattes made you to photograph experiments that he was carrying out with cosmic rays?

He was a friend of mine. When he had a problem with photographing his experiments, he called me, “I want to photograph the ray passing through here”. I said, “How am I going to do that?” Then I invented a system of putting the camera in a fixed place and opening the shutter until this ray passed through. It appears to have worked, but I am not certain.

Did you go as far as to accompany this experiment of his?

Just this one. That was very advanced for me. The things he talked about were very complicated.

He certainly wanted to detect cosmic rays that crash into particles from the Earth’s atmosphere and give rise to other particles that are difficult to be detected and registered on the photographic plates of those days.

Yes, when they passed through some place they would become visible. And that is precisely when I had to photograph them.

Where did you do these experiments?

At the Poly, if I’m not mistaken. I left the Poly in 1946, 1947, as an engineer graduated in mechanics and electricity. And I practically never practiced engineering. I designed Fotoptica’s laboratory, and afterwards ECA’s photography laboratory. I think it was destroyed. It was a very interesting laboratory, with ten enlargers, for ten people to photograph and to develop their photographs, a very fine affair.

What led you to engineering?

I was born in 1924. When I reached the age for studying at university, we were at war. In those days, I was still Hungarian, and Hungary was on the other side. And I couldn’t study cinema, which I loved. I wanted to study abroad, in the United States or in Europe, but with the war I couldn’t go. We gathered the family together for a discussion “What do you want to study? Because you are going to have to study now, you aren’t going to stop. Do you want to be a lawyer?” No I didn’t. “Do you want t be a doctor?’ I did not. “Do you want to be a philosopher?” I didn’t even know what that was, it didn’t even occur to me. “Do you want to do engineering?” I decided, “OK, I’m going to do engineering”. And so I went into the preliminary course at the Polytechnic.

By elimination.

Yes, it was the most palpable thing. I did two years of the preliminary course at the Polytechnic. You went in by an entrance exam. After the entrance exam, seven pupils were left over, me amongst them. Because there were 50 places, but 57 passed. We made a campaign to let the surplus seven in. And we succeeded.

You left the Poly and dropped into Fotoptica?

I am an only child. My mother worked as a cashier, daddy in the shop, with the employees. And I used to help serve at the counter. I always worked in Fotoptica for as long as I could.

How did Fotoptica’s expansion occur?

After my graduation, people came from other places, a guy came from Mesbla, we opened the store in Conselheiro Crispiniano street and we went on opening other branches. The last stage was when we took money lent from a bank to refurbish everything, to put in a laboratory and modern optical equipment, to transform everything into a marvel. There were already 20 or so stores. It so happened that the bank’s interest, suddenly, became impossible to pay. And at that moment we sold out to a bank.

When?

Seven or eight years ago. We divided the money between my four children, my ex-wife and me. There was a bit left for everyone.

How do you see yourself? As a photographer, as sort of Maecenas of the Brazilian documentary cinema, as a businessman, or as a teacher?

I never saw myself as a Maecenas. It was a political ambition to make those films. And obviously it was the time to do so. My life is image. Almost all my children work with image. Pedro is a photographer, João was a photographer, Kiko is an architect; Beatriz is a pedagogue, she doesn’t deal with image. Now, I have a grand-daughter, Pedro’s daughter, who is a cinema assistant. It’s the fifth generation. My grandfather had a photography shop in Hungary. So it was my grandfather, my father, me, Pedro, and now Maria. That’s five generations. I have another grand-daughter who is studying at Faap [Armando Álvares Penteado Foundation] and is now making films as well.

Talking about political ambition, were you imprisoned in the 1970’s?

I no longer remember exactly which year it was. I know that it was after a denouncement. Somebody said that I had sold military binoculars to the guerrillas. Military binoculars are made especially for the Army, they aren’t sold to the public. I was arrested, they interrogated me…

Did they go to your house to arrest you?

They went to Fotoptica. I sat between two guys, I didn’t know what was up, and they asked me a load of questions. I said, “Look, it’s nothing like that”. And I remained there in Tutóia street [São Paulo HQ of the 2nd Army] one week. And folks began to stir. I wasn’t maltreated, but I saw people leaving from maltreatment. My son Pedro was a minor and remained imprisoned for some months.

Why?

Because he was holding meetings in the house in Guarujá. So he had some friends… It was the youngsters who were taking part in that, who were making plans. I knew nothing. I wasn’t aware of everything. They had independence.

Do you think that the way that culture and politics were treated in the years of the dictatorship still projects reflections today?

I think that a natural process of Brazilian development was interrupted. I mean, there was a cut. And for you to redo the cut of the tree? I don’t know to this date what the effect of this is, I don’t, but it had an effect. It changed people’s minds, everything changed.

Was there a certain notion of how a kind of development of a country was being created from this cultural activity?

It was a thing of suggesting ideas. Suggest them, folks, think, think of what Brazil is, how Brazil is, the grandeur of this land, the variety, the most diverse people… It’s something fantastic. And there was an interruption, which lasts almost to this day.

Were the possibilities of a cultural connection that we had with Latin America were aborted at that moment?

No, you can forget the idea of a connection between Brazil and the rest of Latin America. There was perhaps with Argentina, a bit with Uruguay. Chile was very far away and we didn’t even have a plane to the rest of America. Today you have a connection with everything. In the old days, we had a connection with Europe and United States. Only.

Wasn’t there a Latin American movement?

No. It was afterwards that the movement to try to make one began to be studied. We went to a meeting in Viña del Mar, but that was afterwards. The Latin American convergence was later. Guido [Araújo] tried to do the Brazilian one first, the Latin American one afterwards, and now it’s an international journey.

How do you see the lines of development of the Brazilian cinema today?

I think that there is very great progress. Both in ideas and in achievement. There are some very good things. I don’t know where it is going to stop, where it is going to hit. But I think that it’s doing well.

That makes possible a new reflection about ourselves, which country we have built?

Probably. You see people from Rio Grande do Sul, for example, making some very interesting films. They are different from the films made here in São Paulo. Folks are also going to the North and Northeast to film some extremely interesting things. Zelito [Viana] goes into the interior, dealing with the Indians. So there’s a beginning of knowledge, yes there is.

Have you always filmed the themes you have wanted to?

What has always interested me is people, practices, customs, what Brazil is. I used to like this very much, I still do, and I do what I can. When I travel, I always take the camera and see what there is.

Do you stay more here or in Paraty?

Here. Because my social and cultural life is here. Paraty is a paradise.