In the founding documents of the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1948, there is a special reference to a Brazilian. At the opening of his inaugural speech at the 1946 International Health Conference in San Francisco, American surgeon Thomas Parran (1892–1968) expressed his thanks to “Doctor de Paula Souza” and “Doctor Szeming Sze.” These two figures—the sanitarian Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza (1889–1951), representing Brazil, and the diplomat Szeming Sze (1908–1998), representing China—were, as Parran noted, responsible for the efforts that made the conference possible. They played a key role in introducing health as one of the themes of the assembly that created the United Nations, the so-called Charter of the United Nations, a year earlier. This inclusion ultimately enabled the creation of the WHO.

“The UN Charter didn’t even contain the terms ‘health’ or ‘hygiene,’” Paula Souza recalled in an interview with the now-defunct Rádio Excelsior, broadcast on November 26, 1949. In that interview—later cited in a 1984 article in Revista de Saúde Pública—he recounted that he had proposed the creation of “an international public health agency, dependent on the United Nations or affiliated to it.” However, the suggestion was only accepted after “long talks and arrangements,” and the support of the Chinese delegation.

Collection from the USP School of Public Health Memory CenterPaula Souza in his officeCollection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center

Paula Souza was a prominent figure in both Brazilian and international academic circles. He held a doctorate from the newly established School of Hygiene and Public Health at Johns Hopkins University in the United States and became the first director of the School of Public Health at the University of São Paulo (FSP-USP). In 1925, he led a health reform that expanded the traditional infrastructure-focused approach to include health education. Inspired by the North American model promoted by the Rockefeller Foundation, the reform emphasized the creation of health centers and training courses for health educators, aiming to develop what he called the population’s “health consciousness.” “Paula Souza’s great contribution was to focus on training public health agents to prevent the spread of many infectious diseases,” says historian Jaime Rodrigues of the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP), Guarulhos campus.

Coffee-growing elite

The name Paula Souza was already well known and respected by the late nineteenth century, when the future sanitarian was born in Itu, in the interior of São Paulo. His father, Antônio Francisco de Paula Souza (1843–1917), a prominent figure in São Paulo’s coffee-growing elite, was a nationally recognized engineer, state deputy, and founder of the Polytechnic School. He served as its first director for 24 years, until his death, and laid the groundwork for what would later become part of the University of São Paulo (USP).

His son, however, chose the biomedical sciences. At age 16, he enrolled at the São Paulo School of Pharmacy and, three years later, began a second degree at the School of Medicine in Rio de Janeiro. During school vacations, he worked at the Polytechnic School with Swiss-Brazilian veterinarian Roberto Hottinger (1875–1942), who later arranged internships for him in Germany, France, and Switzerland.

Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza Collection / FM-USP Historical MuseumPaula Souza (foreground, left) with colleagues at Johns Hopkins UniversityGeraldo Horácio de Paula Souza Collection / FM-USP Historical Museum

In 1913, after graduating in medicine, Paula Souza began working as an assistant to Hottinger in his laboratory at the Polytechnic School. Together, they conducted a series of experiments to assess the quality of the water distributed in the city of São Paulo. “They were concerned about waterborne diseases such as typhoid fever,” explains social scientist Cristina de Campos, from São Judas Tadeu University, who studied Paula Souza’s career for her master’s degree at the School of Architecture and Urbanism at USP with support from FAPESP.

Hottinger and Paula Souza developed a device called the perfector, based on ozone, to purify water. Later, as director of the São Paulo State Sanitary Service, his first measure was to introduce chlorination of the city’s water supply.

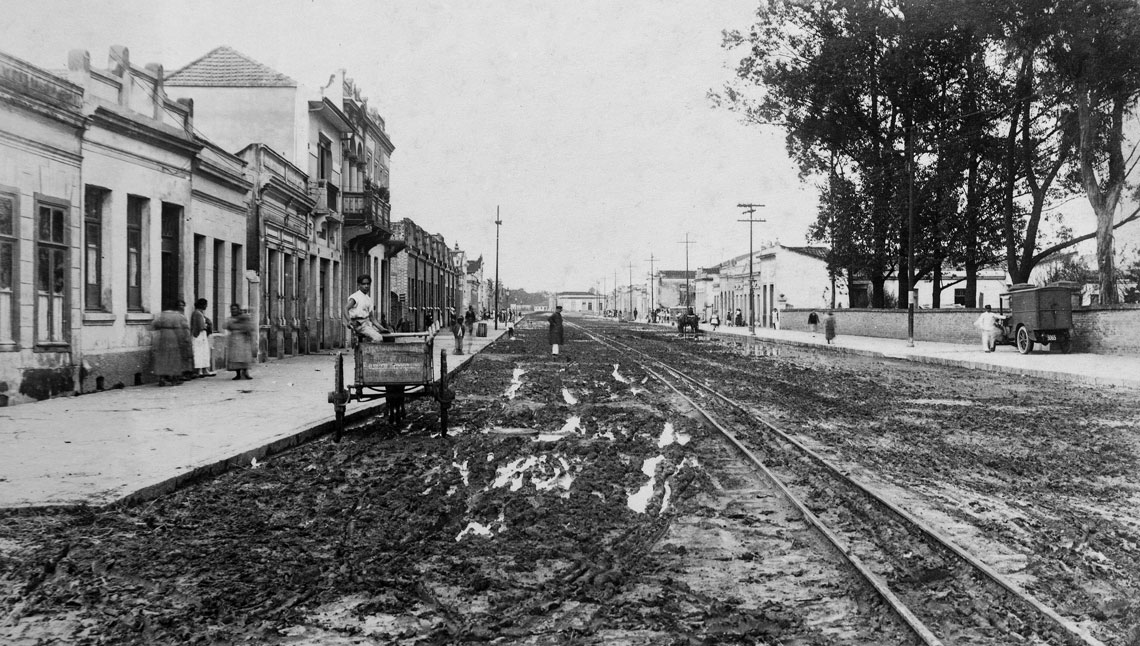

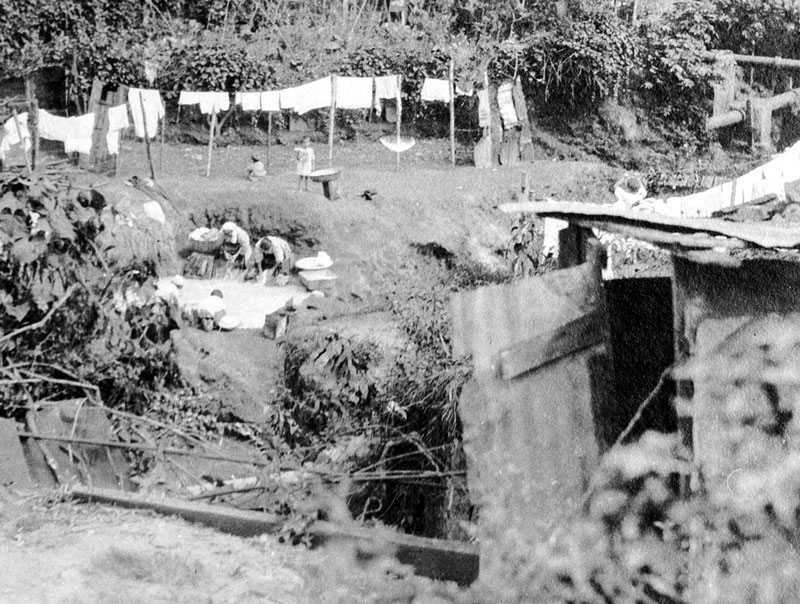

Collection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center Waste from a latrine (right) drains into the Saracura Grande stream, in what is now the Bixiga neighborhood, near an area where washerwomen once worked (left)Collection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center

In 1914, Paula Souza took up the position of assistant professor in the Chemistry Department at the newly founded São Paulo School of Medicine and Surgery. A crucial step in his education followed soon after: a doctorate in hygiene and public health in the United States, supported by the Rockefeller Foundation. His training abroad was made possible by an agreement signed in 1918 between the Rockefeller Foundation and the São Paulo state government, which led to the creation of the Institute of Hygiene—the precursor to FSP-USP (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue no. 264). The agreement provided for two Brazilian doctors to receive scholarships to study at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene.

The selected candidates were Francisco Borges Vieira (1893–1950) and Paula Souza, who became the first Brazilians to earn doctorates in hygiene and public health. “As representatives of São Paulo’s upper elite, they were hand-picked,” notes physician Guilherme Arantes Mello, from UNIFESP, who wrote about this period in Brazilian public health in a December 2011 article in História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos.

Paula Souza assumed the directorship of the Institute of Hygiene upon his return from the United States in 1921. Ten years later, under his leadership, the institute was transformed into the State School of Hygiene and Public Health and became part of USP in 1934. In 1945, it was renamed the School of Hygiene and Public Health, still under his direction. The institution received its current name in 1969.

Collection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center Paula Souza at the signing ceremony for the WHO Constitution, July 22, 1946, in New YorkCollection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center

In 1922, Paula Souza was appointed head of the São Paulo State Sanitary Service. Three years later, he introduced a new Sanitary Code, which placed particular emphasis on health education for the city’s residents. He argued that a sanitized environment would be ineffective without the development of a “sanitary culture.” Economist Maria Alice Rosa Ribeiro, from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), reproduces in her book História sem fim… Inventário da saúde pública (Never-ending story… Public health inventory; UNESP, 1993) an excerpt from a lecture in which he explains this view—albeit in language that reflects the prejudices of his time: “Let us put the ignorant caboclo in the boss’s house and the boss in the caboclo’s hut, or the resident of Higienópolis in the tenement of Brás and the uneducated family in the palace of the former, and see how right I am: rapid would be the transformation of the hut and the mucambo into places compatible with a dignified life, as well as that of the mansion and the palace into the most dangerous dens of disease and misery.”

Within this framework, the individual needed to be educated in order not to endanger society as a whole. “There was a social demand for epidemic control, which affected both rich and poor and caused harm to economic activities,” explains nurse Maria Cristina da Costa Marques, coordinator of the FSP-USP Memory Center, which houses Paula Souza’s archive. “This was a model that developed in tandem with a broader political and economic project to strengthen the state.”

Collection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center Health educator (right) instructs a woman on improving her children’s hygieneCollection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center

Influenced by eugenics—a racist pseudoscience that advocated for the improvement of the “Brazilian race”—this vision aimed to produce a nation of disciplined, healthy, and productive workers. According to Marques, Paula Souza, like many sanitarians of his time, was influenced by eugenics.

Paula Souza brought from the United States the model of health centers with an essentially preventive role. These centers aimed to promote good hygiene practices and disseminate health information through personal guidance, lectures, printed materials, and exhibitions. Health educators played a central role in this work, conducting outreach in schools and during home visits. To address the shortage of nurses, a Health Education Course was established in 1925 at the Model Health Center located within the Institute of Hygiene. It was designed specifically for elementary school teachers, who were trained to support public health efforts through education.

From São Paulo, the health center model spread throughout Brazil. “It was a Rockefellerian tsunami,” jokes Mello. In Bahia, a similar health reform was launched in 1925. Nildo Batista Mascarenhas, a health nurse at the State University of Bahia (UNEB), explains that this reform likewise sought to control infectious diseases through educational efforts in health centers and home visits, conducted by health visitors—the local term for health educators. Paula Souza and Antônio Luís Cavalcanti de Albuquerque de Barros Barreto (1892–1954), who led Bahia’s Undersecretariat of Health and Public Assistance, “were products of the same political project for public health, aligned with the group of Carlos Chagas [1879–1934] and other prominent hygienists,” says Mascarenhas, a coauthor of an article on public health in Bahia published in November 2020 in Revista Baiana de Saúde Pública. Barros Barreto, the son of a prominent Pernambuco family, also received a Rockefeller Foundation scholarship and earned a doctorate in Public Health from Johns Hopkins University.

The 1930 Revolution, which made Getúlio Vargas the Brazilian president, marked the beginning of a period of centralized health policymaking that curtailed state-level initiatives. “The new health policy gradually shifted toward medical and hospital care, to the detriment of community-based public health actions,” notes Mascarenhas. Amid political instability and opposition in the state Legislative Assembly, Paula Souza was unable to implement all of the health centers he had envisioned: of the eight planned, only three were established—the model center at the Institute of Hygiene and two others in the Brás and Bom Retiro districts.

Even so, Mascarenhas argues, the seeds of a new model of preventive medicine had been planted. He sees the role of health educator or health visitor as a precursor to today’s community health worker, serving as a bridge between health services and households. “This model remains in Brazilian public health,” he observes. “The health center, with its community-based approach integrated into family life, is a clear historical legacy of that strategy.”

Collection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center As part of health education, children learn how to brush their teeth at schoolCollection from the USP School of Public Health Memory Center

Nutritional guidance was a key element of the health education promoted by Paula Souza, who had encountered the profession of nutritionist during his time in the United States. Between 1932 and 1933, he led the first survey of dietary habits among São Paulo’s population. The results revealed difficulties in the consumption of beans relative to other foods. In response, he proposed the creation of popular “bean kitchens.” “District kitchens would be set up, where people could purchase cooked beans in small quantities—much like buying bread rolls at the bakery, which had by then replaced home-baked bread. At the time, pressure cookers were not widely available, and beans, though highly nutritious, required the most time and fuel to prepare,” explains Rodrigues. The Industry Social Service (SESI) even opened a district kitchen in the Tatuapé neighborhood, but the broader plan for bean kitchens did not move forward.

With support from FAPESP, Rodrigues compiled 2,600 documents related to the sanitarian, presented in the Analytical Inventory of the Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza Archive, published by FSP-USP in 2007. The research proceeded relatively smoothly, as Paula Souza had preserved all his correspondence and newspaper clippings that mentioned him. “There were even carbon copies of the letters he sent. It was as if he intended to construct a memory that would endure beyond his lifetime,” says Rodrigues.

From 1927 to 1929, Paula Souza worked in Geneva at the Health Organization of the League of Nations, which aimed to address global public health challenges. Although the League was later dissolved after the Second World War, part of its mandate was absorbed by the newly established WHO. Paula Souza was appointed one of the WHO’s vice presidents in 1948, a position he held until his death three years later. He died of a massive heart attack at the age of 62, on the eve of a planned work trip.

The story above was published with the title “Public health guidelines” in issue 351 of May/2025.

Projects

1. A social history of food in the city of São Paulo (1920s to 1950s) (n° 05/51165-3); Grant Mechanism Postdoctoral Fellowship in Brazil; Supervisor Maria da Penha Costa Vasconcellos (USP); Beneficiary Jaime Rodrigues; Investment R$63,467.40.

2. City and hygiene in São Paulo, 1925–1945: Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza and the institutionalization of public health as an academic discipline (n° 98/12910-0); Grant Mechanism Master’s fellowship in Brazil; Supervisor Maria Lúcia Caira Gitahy (USP); Beneficiary Cristina de Campos; Investment R$29,812.34.

3. Representations of American public health: Photographs taken by Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza, 1918–1920 (n° 19/19712-7); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Cristina de Campos (USJT); Investment R$32,884.56.

Scientific articles

CAMPOS, C. de. O sanitarista, a cidade e o território. A trajetória de Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza em São Paulo. 1922-1927. PosFAUUSP. Vol. 11. June 20, 2002.

CANDEIAS, N. M. F. Memória histórica da Faculdade de Saúde Pública da Universidade de São Paulo – 1918–1945. Revista de Saúde Pública. Vol. 18. Dec. 1984.

MASCARENHAS, N. B. & SILVA, L. A. A política de saúde na Bahia (1925-1930). Revista Bahiana de Saúde Pública. Vol. 43. no. 1. Nov. 25, 2020.

MELLO, G. A & VIANA, A. L. d’Á. V. Centros de saúde: Ciência e ideologia na reordenação da saúde pública no século XX. História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos. Vol. 18, no. 4. Dec. 2011.

RODRIGUES, J et al. Inventário analítico do Arquivo Geraldo Horácio de Paula Souza. São Paulo: School of Public Health/USP, 2007.

RODRIGUES, J. & VASCONCELLOS, M. da P. C. A guerra e as laranjas: Uma palestra radiofônica sobre o valor alimentício das frutas nacionais (1940). História, Ciências, Saúde – Manguinhos, Vol. 14, no. 4. Dec. 2007.

Books

RIBEIRO, M. A. R. História sem fim… Inventário da Saúde Pública. São Paulo: Unesp, 1993.

RODRIGUES, J. Alimentação, vida material e privacidade: Uma história social de trabalhadores em São Paulo nas décadas de 1920 a 1960. São Paulo: Alameda, 2011.