More than one year into the pandemic, children and adolescents still appear to be less vulnerable than adults to infection by the novel coronavirus. In the US, the country currently with the highest SARS-CoV-2 infection rates and the most available data, less than 14% of COVID-19 cases—and far less than 1% of deaths—have involved children and teenagers under 19, according to data published in May by the American Academy of Pediatrics. And while individuals in this age group typically have milder symptoms of the disease, they are not entirely immune to severe complications. In a very small number of cases—approximately one in every 50,000—children develop a systemic inflammation that, if not treated promptly, often in an intensive care unit, can lead to death. First identified early in the pandemic by physicians in the UK, Italy, and the US, this hyperinflammatory condition, referred to as pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome (PIMS), is being investigated in studies that are attempting to distinguish it from other health conditions with similar symptoms, such as Kawasaki disease or toxic shock syndrome from bacterial infections.

A recent Brazilian study suggests that the cause of multiorgan damage in PIMS may be more than just an exacerbated response from the immune system as it tries to fight off the virus, as is commonly the case with COVID-19. In severe cases leading to death, the SARS-CoV-2 virus appears to cause direct damage to the heart, the digestive tract, and even the brain. These findings, reported in a paper published April 29 in EClinicalMedicine, came from analyzing autopsies on five children and adolescents who died from COVID-19 in São Paulo, southeastern Brazil. The lead authors of the paper are pathologist Amaro Nunes Duarte Neto and biologist Elia Caldini of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine (FM-USP). Their findings help to explain why clinical presentations of PIMS—of which there were 813 reported cases in Brazil as of March 13 (including 139 in the state of São Paulo)—can vary from one individual to another, and may help to inform more effective ways to treat the syndrome.

“This was the first time the virus was found to be directly infecting heart, gut, and brain cells in children. We confirmed these observations using different techniques,” says Marisa Dolhnikoff, a professor of pathology at FM-USP who led the study. “Our findings show that the lesions caused by SARS-CoV-2 in different organs are directly associated with the inflammatory response and multisystemic involvement in PIMS,” she says.

Last year, at least 10 pediatric COVID-19 patients admitted to Intensive Care Units (ICUs) at FM-USP’s Hospital das Clínicas ultimately died of the disease. Five patients, ranging from a few months to 15 years old, were autopsied. Although seemingly a small number, this is the largest series of autopsies on children who died from COVID-19.

At the Autopsy Room Imaging Platform (PISA) facility, the team led by Dolhnikoff and pathologist Paulo Saldiva performed the autopsies as part of a project funded by FAPESP, the Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The pathologists used a portable ultrasound scanner to view the different organs and guide them as they collected small samples of tissue using coaxial needles, a minimally invasive procedure that family members are more likely to accept.

In these autopsies, two major patterns of severe COVID-19 were observed: a primarily pulmonary disease, and a multisystem syndrome with the involvement of several organs. The two patients exhibiting the first pattern had severe pre-existing medical conditions. One was a less-than-one-year-old baby born prematurely with a genetic syndrome, and the other was a teenager with an advanced form of cancer. In both cases, the virus primarily affected the lungs, as occurs in most coronavirus cases in adults.

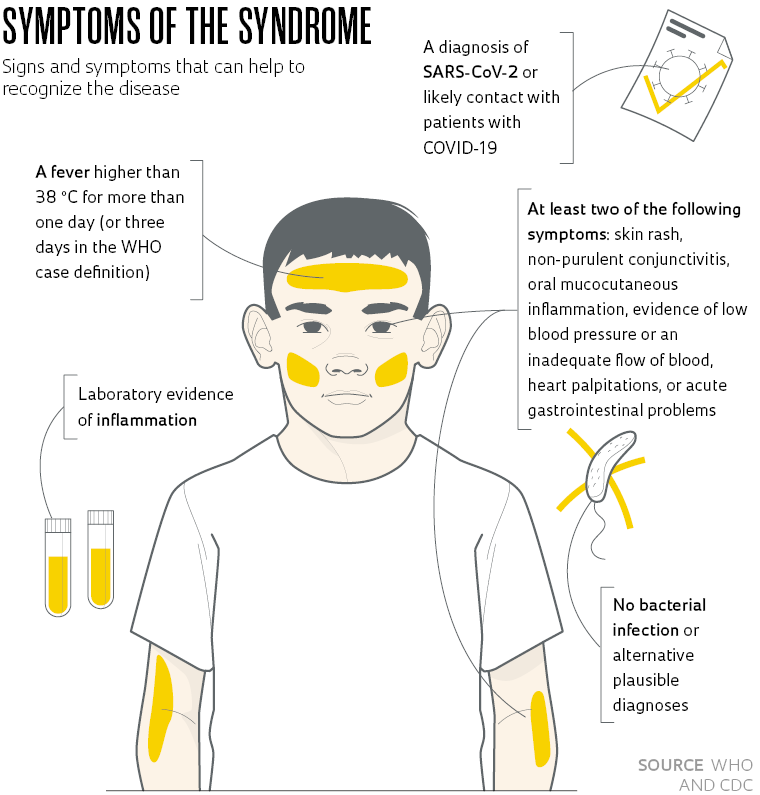

The second disease pattern was PIMS and was characterized by lesions primarily in the digestive tract, heart, and brain. The three children, aged 8 to 12, were previously healthy and, within a few days of becoming infected with SARS-CoV-2, developed symptoms consistent with PIMS—as officially described in case definitions by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2020 (see table). The patients with PIMS presented with only mild lung involvement. They instead died from severe lesions in other organs caused by the action of the virus itself combined with an exacerbated immune response.

One of the children developed an acute inflammation in the digestive tract (colitis), while the second presented with myocarditis (an inflammation of the heart muscle) and endocarditis (an inflammation of the inner lining of the heart chambers)—this case was described in detail in a paper published in October in The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. The most affected organ in the third child was the brain. This patient presented with acute encephalopathy with altered mental status and seizures. “The presence of the virus in these organs suggests that it plays a direct role in the observed multisystem inflammatory involvement,” says Werther Brunow de Carvalho, medical director of the pediatric and neonatal ICUs at USP’s Children’s Hospital, and one of the authors of the study. “So the cause of PIMS is not just a widespread inflammatory response,” he says.

In the brain, the virus was detected in perivascular astrocytes (support cells that nourish neurons), while in the intestines it was found in smooth muscle cells, which are responsible for the contractions that move food through the digestive system. In the heart, the virus was found to have infected cardiomyocytes—the muscle cells that make the heart beat. In all three cases, the researchers also found copies of the coronavirus infecting the endothelium—a layer of cells that lines the interior surface of blood vessels. This led the pathologists to consider the hypothesis that the virus, after penetrating the respiratory system, finds its way to distant target organs through the blood. For reasons still unknown, the target tissues vary from one individual to another. “In addition to mediating the spread of the virus, infection of the endothelium with SARS-CoV-2 is the primary cause of the pulmonary thrombosis observed in these children, as has also been documented in adult patients with COVID-19,” explains Dolhnikoff.

“The data from these autopsies suggests that children may require a different treatment approach than adults,” Saldiva said in a testimonial in early May in the “Research from Home” section on the Pesquisa FAPESP website. “The answer might be to use high-dose anti-inflammatory drugs combined with an anticoagulant, as there is a very significant thrombotic component.”

The UK National Health Service (NHS) was the first to sound the alarm about the syndrome. In April 2020, a little more than a month after the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the NHS issued an alert to pediatricians about a small but rising number of children with a rare and serious syndrome that could be linked to coronavirus (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 292). The clinical symptoms were unusual. Patients presented with symptoms similar to Kawasaki disease—a rare illness that causes inflammation in the blood vessels (vasculitis) and can develop after a viral infection—and toxic shock syndrome, a condition caused by a bacterial infection that can lead to a significant drop in blood pressure (shock).

Caldini / FM-USP Department of Pathology

An artificially colored electronic micrograph of a brain cell (oligodendrocyte) infected with copies of the novel coronavirus (

arrows in the detail)

Caldini / FM-USP Department of PathologyAs the virus spread throughout the West, several distinguishing characteristics of PIMS soon became apparent. Population studies showed that PIMS occurs primarily in teenagers and children slightly older than those typically affected by Kawasaki disease (up to 5 years), and causes symptoms such as myocarditis, shock, gastrointestinal symptoms (abdominal pain, diarrhea or vomiting), and neurological symptoms (headache, dizziness). PIMS also appears to be somewhat more frequent in boys and in non-Caucasians.

In a report on 56 PIMS cases at 17 pediatric ICUs in Brazil, published in November in Jornal de Pediatria, Fernanda Lima Setta, the medical director of the Pediatric ICU Division of D’Or São Luiz, a hospital network in Rio de Janeiro, found that 70% of cases were boys and 59% were non-Caucasian—in the US, these percentages are respectively 50% and 63%. For reasons unknown, mortality rates appear to be higher in Brazil than in the US. As of March 29, the CDC had reported 3,185 cases of PIMS and 36 deaths in the US (1.1% of the total), while the Brazilian Ministry of Health had reported only 813 cases but 51 deaths (6.3%). “It is likely that the apparently higher death rate is a result of underreporting of the syndrome in Brazil,” says Lima Setta. Due to the low testing rates in the country, it is likely that only the most serious cases and deaths are being reported here, which can artificially inflate the case-fatality rate (less severe cases are underreported). Other contributing factors, says the pediatrician, could be physicians’ lack of training on how to recognize the syndrome and parents failing to seek immediate medical attention for lack of knowledge about the disease—although we cannot rule out that poor healthcare in some regions of Brazil may be to blame in some cases.

Also in November, immunologists in Italy and Sweden, led by Petter Brodin of Karolinska Institutet, compared the immune response in children with PIMS against patients with Kawasaki disease, and found differences that can support more effective diagnosis and treatment: each disease activates slightly different populations of T cells, and the exacerbated inflammatory response is mediated by different inflammatory compounds: interleukin 6 (IL-6) plays a larger role in PIMS, while interleukin 17A (IL-17A)—which is normally released in autoimmune diseases—is most significant in Kawasaki disease.

It is important to emphasize, says Lima Setta, that PIMS is an extremely rare condition and that, with proper treatment, children recover well. Depending on case severity, the treatment may include the use of anti-bodies and potent anti-inflammatory drugs, combined with compounds to reduce blood coagulation. “With each wave of the pandemic, we expected to see a slew of pediatric cases in ICUs,” says Setta. “Fortunately, that didn’t happen.”

In Brazil, not only has there been an apparently higher rate of deaths from PIMS, but the overall number of children dying from COVID-19 is abnormally high. As of March 15 this year, at least 852 children under the age of 10 had died. Some projections indicate this figure is nearly 10 times higher than in the US, the country with the highest death toll from the disease.

Project

Modern autopsy methods in investigating human diseases (MODAU) (nº 13/21.728-2); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Paulo Hilário Nascimento Saldiva (USP); Investment R$5,818,510.25.

Scientific articles

DUARTE-NETO, A. N. et al. An autopsy study of the spectrum of severe COVID-19 in children: From SARS to different phenotypes of MIS-C. EClinicalMedicine. Apr. 25, 2021.

DOLHNIKOFF, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 in cardiac tissue of a child with COVID-19-related multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. Oct. 1, 2020.

LIMA-SETTA, F. et al. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Brazil: a multicenter, prospective cohort study. Jornal de Pediatria. Nov. 9, 2020.

CONSIGLIO, C. R. et al. The immunology of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children with COVID-19. Cell. Nov. 12, 2020.

Republish