The end of a rule allowing pharmaceutical patent term extensions in Brazil should provide billions of dollars in savings for the National Healthcare System (SUS), according to estimates prepared by researchers at the Institute of Economics of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (IE-UFRJ). The group analyzed the prices and purchase volumes for nine drugs from 2014 to 2018, based on records kept at the Healthcare Logistics Department (DLOG), at the Executive Office of the Brazilian Ministry of Health. Based on these data, they estimated an expenditure of roughly R$6.8 billion over the coming years on these compounds if their patents were to remain extended. “Being able to purchase generics available in the international market would slash this amount by R$1.2 billion,” says economist Julia Paranhos, a professor at IE-UFRJ and one of the authors of the study, published in the journal Cadernos de Saúde Pública. Assuming the highest possible reductions—some generics are sold as much as 99% cheaper on the international market—the potential savings for the SUS could be as high as R$3.9 billion.

Patents provide their owners with an exclusive right to sell a drug for a period of 20 years from the date the application is filed with the National Institute of Industrial Property (INPI). However, article 40 of the Industrial Property Act (LPI) of 1996 established that if the patent office took longer than 10 years to grant a patent, the delay would be offset by an extension of the patent’s term. Paranhos explains that the patent office had no experience reviewing pharmaceutical patent applications prior to 1996. With the early enactment of the LPI, the INPI had to structure a dedicated department for this purpose, while applications were already being filed. “This was predicted to have an impact on the time taken to review applications, so the decision was made to add this provision under article 40 in order to offset the delay,” explains Paranhos. The problem is that this privilege prevents competitors from entering the market, as generic copies of brand-name drugs are only permitted when patent protection has expired. This gives patent owners the power to sell their products at higher prices, affecting public and private healthcare costs.

Economist Eduardo Mercadante, who is studying a PhD at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), in the UK, notes that pharmaceutical patent applications typically take 13 years to be finally granted in Brazil, “directly affecting the terms of pharmaceutical patents, with article 40 becoming a rule rather than an exception as initially intended,” says the researcher, who coauthored the study. “This is highly problematic in a country like ours, which is highly dependent on foreign technology and has a large public healthcare system,” adds Paranhos.

Between 2014 and 2018, DLOG spent R$10.6 billion purchasing the nine drugs analyzed by the researchers. “It’s impressive how just a handful of drugs can create such significant budget pressure,” says Mercadante. The monoclonal antibody adalimumab, used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel disease, had the highest budget impact. Purchases of the drug cost a total of approximately R$3.8 billion during the study period. Another particularly expensive drug was eculizumab, used to treat paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria, a rare type of anemia that can cause chronic kidney disease, pulmonary hypertension, among other adverse effects. The government is estimated to have spent just over R$2.3 billion on purchasing the drug.

At least three other studies, using different methodologies, also estimated the impacts of patent extensions on the SUS budget. One of these studies, carried out in 2016 by the same IE-UFRJ group, estimated the additional cost of purchasing nine other patent-extended drugs at R$2.1 billion—two of these drugs are also on the list analyzed in the most recent research by Paranhos and Mercadante: sofosbuvir, for chronic hepatitis, and adalimumab. A 2017 study published in Cadernos de Saúde Pública by researchers at INPI and the National Institute of Technology (INT), in Rio de Janeiro, arrived at a potential additional cost of R$288.4 million for three antiretroviral drugs used against HIV. More recently, an audit by the Brazilian Audit Court (TCU) looked at 11 compounds purchased between 2010 and 2019. According to the auditors, the SUS could have saved around R$1 billion without patent term extensions.

The impact could have been smaller, as the Ministry of Health has the power to request prioritized examination of patent applications for medicines that are needed in government healthcare programs or that are considered strategic. This would fast-track the patent reviews and avoid patent term extensions beyond 20 years. But according to a TCU report, the ministry has used this prerogative only 16 times since the rule came into effect in 2008—at least 74 drugs are estimated to have benefited from the extension.

In 2021, Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court (STF) finally settled the matter: by 9 votes to 2, it ruled article 40 of the LPI to be unconstitutional. “The decision has retroactive effects,” explains Pedro Marcos Nunes Barbosa, a professor in the Department of Law at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-RJ). “All healthcare-related patents with extended terms—including those still under review and which could benefit from an extension in the future—have lost the privilege.”

Some pharmaceutical companies are now trying to circumvent the STF decision by bringing actions in a federal court in Brasília. “They admit there is no legal basis for extending patent terms in Brazil, but as this exists in other jurisdictions and the INPI lacks the resources to timely review applications, they are trying to apply, by analogy, regulations that exist in other countries to extend the validity of their patents in Brazil,” he explains.

The INPI’S budget for operation and investments has fallen from R$80.1 million to only R$34 million over the last five years

There are more than 30 lawsuits of this type currently pending in the country. In at least two, Barbosa notes, urgent relief has been granted to the patent owners. “None of them has yet obtained a favorable decision, but it is enough for one of them to succeed to create legal insecurity in the market, as other companies will use the same strategy to extend their patents and prevent competition,” he says. Barbosa explains that pharmaceutical companies spend a lot of time and money preparing to launch their generics and biosimilars as soon as the patent on the brand-name drug expires. “They need to submit quality, safety, and efficacy data to ANVISA [the Brazilian Health Regulatory Agency] for registration, which can take months, often years.” According to Barbosa, the amount of planning required becomes impossible if there is uncertainty about the duration of the monopoly.

Despite the positive impacts on the SUS budget, some experts argue that the STF decision fails to address the root cause of the problem: the length of time it takes to examine patent applications. “The INPI significantly underperforms large international patent offices,” says Matheus Ferreira Bezerra, a professor of law at the State University of Bahia (UNEB). In a recent paper, economist Eduardo Mercadante analyzed the patenting process in Brazil, with a special emphasis on the pharmaceutical sector. He benchmarked the INPI against the five largest patent offices in the world—the United States, China, Japan, South Korea, and Europe—as well as India and Mexico. He found that Brazil’s patent office receives one of the smallest numbers of patent applications each year—just slightly more than Mexico—but takes the longest to issue a determination on them.

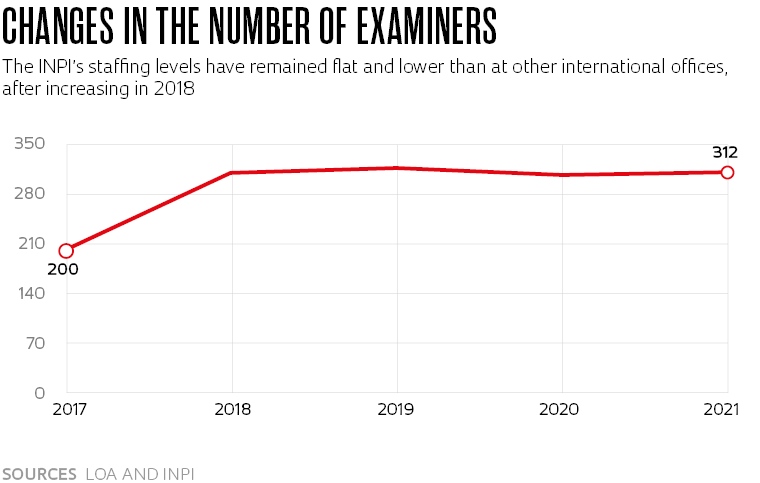

Mercadante believes the bottleneck is mainly attributable to the limited number of examiners. “There were just 318 in 2019, while China had more than 12,000 and the United States more than 8,000,” he says. To make matters worse, each examiner at INPI had a backlog of 641 applications—the international average is 112 per examiner. “Patent applications sit in a queue for seven years on average before they are examined, and the examination process itself takes around three-and-a-half years.”

The situation has gotten even worse in recent years. Since 2019, the INPI has seen its contingent of examiners shrink to 312. “They just can’t handle the backlog,” says Mercadante. For Bezerra, “the delay could discourage pharmaceutical companies from registering new drugs in Brazil.” Elize Massard da Fonseca, a public health specialist and a professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV) in São Paulo, disagrees that Brazil will lose investor interest. “The delay in granting patents may be a counter-incentive, but Brazil is the sixth largest pharmaceutical market in the world and will continue to attract the interest of large companies.”

From 2013 to 2021 the number of national and foreign patents filed annually at INPI fell from 34,000 to 26,900, according to data from the World Intellectual Property Organization, recently released by the Brazilian Intellectual Property Association (ABPI). Globally, meanwhile, total applications grew from 2.57 million to 3.22 million.

In August 2019 the INPI launched a plan to reduce the number of patent applications pending a decision. Its strategy has been to review applications submitted up to 2016 based on previous determinations issued by foreign offices—most applications made in Brazil have corresponding applications in other countries, as 70.5% are filed by foreign applicants. The idea, says Alexandre Dantas, an assistant in the INPI’s Department of Patents, Computer Programs, and Integrated Circuit Topography, is to speed up the technical examination process and reduce waiting times for a final determination. “We’ve simplified the examination process by requesting that the applicant adjust the application to match the version approved by the international office,” he explains. The INPI had a backlog of nearly 149,900 pending applications. The new strategy is estimated to have reduced this backlog by 76.8% as of 2021—according to Mercadante, however, this percentage refers only to applications that could be included under the plan in August 2019, and excludes many others that have become pending since then. “My estimate is that the reduction has been more to the tune of 28%,” he says.

The INPI has claimed it has successfully reduced average time to first examination to 2.4 years from filing the application. This has accelerated the time taken to reach a final determination, which in 2022 is an average of 5.8 years in the pharmaceuticals and biopharmaceuticals segment, counting from the request for technical examination. According to Dantas, the reduction was made possible in part because applications are no longer being submitted to ANVISA for review. The agency previously had to issue a preliminary opinion when granting patents of this nature. “We have accelerated the process by eliminating this step.” In Mercadante’s view, however, it is important that ANVISA continue to play a role in the process. He adds that: “The INPI’s strategy is less efficient than it would seem, as it limits the examiners’ autonomy, grants more applications than it should, and allows lower-quality inventions to receive patent protection.”

In any case, the INPI is likely to struggle to maintain its fast-tracked examination process. In the last five years, the office’s budget for operation and investments has been progressively diminished, from R$80.1 million in 2018 to only R$34 million in 2022. Meanwhile, the amount of funds held as a contingency reserve has jumped from R$258.5 million to R$371.5 million. “New examiners need to be hired and trained to ensure the smooth operation of the INPI,” says Bezerra. For Paranhos, no less important is ensuring its financial and administrative autonomy, “which is provided for by the law creating the INPI and by the LPI but is still far from being put into practice.”

Scientific articles

MERCADANTE E. & Paranhos J. Pharmaceutical patent term extension and patent prosecution in Brazil (1997-2018). Cadernos de Saúde Pública. vol. 38, n. 1, pp. 1–13. 2022.

PARANHOS J., Mercadante E. & Hasenclever L. O custo da extensão da vigência de patentes de medicamentos para o Sistema Único de Saúde. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. vol. 36, n. 11, pp. 1–13. 2020.