GUILHERME LEPCAIt arrived without any pomp, bands playing music or speeches. On an unspecified date in January 1991, at the start of FAPESP’s traditional 20-day holiday period, the first signs of the internet in Brazil started coming into one of the Foundation’s computers. Everything that is now known in Brazil about the global computer network comes from what took place on that site 20 years ago. “For us the internet’s arrival was not a surprise, we had been waiting for it, because it was growing in the United States and we knew that it would be easier to make a Digital brand computer talk with another IBM computer, for example,” says Demi Getschko, who at the time was the Chief Officer of FAPESP’s Data Processing Center and who is now the CEO of the Núcleo de Informação e Coordenação do Ponto BR (Information and Coordination Center of Dot BR) (NIC.br), an entity that is the executive branch of the Comitê Gestor da Internet (Internet Management Committee) (CGI) and which coordinates the network’s services in Brazil. The internet’s arrival at the Foundation was due to there being a direct link with Fermilab (in the town of Batavia, state of Illinois, USA), the high energies physics laboratory that specialized in the study of atomic particles. This line, which was connected in 1989, gave Brazilian researchers access to information and contacts with their peers at the North-American institution and others in that country as well as in Europe, by means of one of the internet’s predecessors, Bitnet. The connection worked with a point-to-point telephone with no dialing, by a copper wire that was inside an underwater cable, because at that time there were no optic fibers for this type of service. It was operated by the Academic Network at São Paulo, Ansp, which was created and has been financially supported by FAPESP since 1988 in order to provide electronic communications between the State of São Paulo’s main teaching and research institutions.

GUILHERME LEPCAIt arrived without any pomp, bands playing music or speeches. On an unspecified date in January 1991, at the start of FAPESP’s traditional 20-day holiday period, the first signs of the internet in Brazil started coming into one of the Foundation’s computers. Everything that is now known in Brazil about the global computer network comes from what took place on that site 20 years ago. “For us the internet’s arrival was not a surprise, we had been waiting for it, because it was growing in the United States and we knew that it would be easier to make a Digital brand computer talk with another IBM computer, for example,” says Demi Getschko, who at the time was the Chief Officer of FAPESP’s Data Processing Center and who is now the CEO of the Núcleo de Informação e Coordenação do Ponto BR (Information and Coordination Center of Dot BR) (NIC.br), an entity that is the executive branch of the Comitê Gestor da Internet (Internet Management Committee) (CGI) and which coordinates the network’s services in Brazil. The internet’s arrival at the Foundation was due to there being a direct link with Fermilab (in the town of Batavia, state of Illinois, USA), the high energies physics laboratory that specialized in the study of atomic particles. This line, which was connected in 1989, gave Brazilian researchers access to information and contacts with their peers at the North-American institution and others in that country as well as in Europe, by means of one of the internet’s predecessors, Bitnet. The connection worked with a point-to-point telephone with no dialing, by a copper wire that was inside an underwater cable, because at that time there were no optic fibers for this type of service. It was operated by the Academic Network at São Paulo, Ansp, which was created and has been financially supported by FAPESP since 1988 in order to provide electronic communications between the State of São Paulo’s main teaching and research institutions.

Bitnet, which is the abbreviation of Because It’s Time Network, was widely used by researchers abroad. It utilized a computer language created by the company IBM. Ansp operated with the Decnet network, a computer network consisting of Digital computers. Special conversion software enabled one machine to talk to another. Since the internet developed in the North American academic area and since Fermilab also decided to get on this network without switching off the Bitnet or Decnet connections, Fapesp, via the Ansp network, also joined. From this initial moment until 1994, when the commercial internet got underway in Brazil, Fermilab’s connection provided all of Brazil’s internet transmissions with other countries.

There is no record of the content of the first internet messages that reached Brazil. Getschko and his team made no recordings and do not remember what was said in the first e-mails. For them, that moment was all about another network that had to be managed and made to work, and what is obvious is that nobody, not even those in the United States, had any idea of the success that it would achieve within just a few short years.

However, to receive the internet, Getschko’s team prepared themselves. The preparations began in 1990, when the Ansp engineer and systems analyst Alberto Gomide visited Fermilab to find out about the new technology. “They were already saying there that they were going to migrate to the internet, with TCP/IP, and that the network would be called the Energy Science Network (ESNet),” says Getschko. “It was decided that when Fermilab changed over to the internet, we would go with them,” he recalls. The Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP) is the main protocol, or language, used by the internet. The software to receive the internet in Brazil was called Multinet. It was purchased from the North-American company TGV and was installed on FAPESP’s Digital brand VAX computer by Joseph Moussa, who was Ansp’s network software expert at that time. Multinet had characteristics in common with the Digital brand computers and could take the place of the router in the connection with the new network.

“The right way to connect the internet would have been to use an external box, a router, which we were only able to get hold of a year later,” says Getschko. The Multinet software installed by Moussa was specified by Gomide and was able to establish the connection using an interface that was common to Digital brand computers. “When the Multinet software arrived, in the middle of Gomide’s vacation, Moussa unpacked it, got the tapes, which were DECtapes [magnetic tapes for storing Digital data and software], installed it in the VAX computer and was successful in running the software and testing the first small packets [packets are the means used on the internet to identify the electronic signals of data with information],” recalls Getschko.

“The right way to connect the internet would have been to use an external box, a router, which we were only able to get hold of a year later,” says Getschko. The Multinet software installed by Moussa was specified by Gomide and was able to establish the connection using an interface that was common to Digital brand computers. “When the Multinet software arrived, in the middle of Gomide’s vacation, Moussa unpacked it, got the tapes, which were DECtapes [magnetic tapes for storing Digital data and software], installed it in the VAX computer and was successful in running the software and testing the first small packets [packets are the means used on the internet to identify the electronic signals of data with information],” recalls Getschko.

Gomide said that at the time he did not see much difference between the two technologies. “Decnet was as complete as the internet itself. Bearing in mind that there was not even any idea of www at that point, all the connection possibilities with other machines were virtually the same as the ones that we had with Decnet. The only difference with the implementation of the .br domain for e-mails,” said Gomide in an interview for a forthcoming FAPESP book on the subject (the authors are Claudia Izique, Marcos de Oliveira and Roberto Tanaka). At that point in the development of networks, the messages were used for correspondence and for swapping data, and it was impossible to send or receive photos, for example. The connection with Fermilab was one of 9,600 kilobytes (Kbps) – up until September 1990 it did not go above 4,800 Kbps -, which is a lot less, for instance, than a domestic connection nowadays of 1 megabyte per second (Mbps) or Ansp?s current connection with the United States, of 10 Gigabytes per second (Gbps).

Open and simple

At the end of the 1990’s, Bitnet and Decnet, along with other proprietary networks, were in decline and the internet grew and spread TCP/IP, which was an open protocol rather than belonging to a specific manufacturer as the other ones did. “Up until the 1990’s there was no technology available to make the networks grow in TCP/IP on a large scale. In the 1980’s, the technology regarding fiber optics and copper wire based modems had already been developed. However, it was still necessary to solve the problem of the protocols to enable computers to talk to each other. This restricted the internet?s expansion,” according to Luís Fernandez Lopez, professor of medical IT at USP’s Medical School and coordinator of the Ansp network. “The great advantage of TCP/IP is that it’s an open and uncomplicated protocol. Because of this, everyone went around creating programs, boards, software and hardware,” he says. “The important thing about the internet is the withdrawal of the computers from the system because the communication does not occur directly between them [large computers or mainframes], but instead through routers [which look for the best route in order to transfer the electronic packets that the messages are transformed into]. The internet became extremely flexible and easily expandable,” explains Getschko.

The experience of Ansp’s team allowed Fapesp, in addition to becoming the Brazilian connection with the internet, to transform itself into the technical center of the start of the Brazilian internet, including serving the National Teaching and Research Network (RNP) created by the Ministry of Science and Technology. The RNP was set up in 1989 and was getting ready to link itself to the web in 1990, which ended up happening in 1992, providing access to a number of the country’s research institutions. FAPESP’s computing group was set up when the Foundation decided to create a network in order to get onto the Bitnet, which had begun to work in 1981, developed by researchers at the University of the City of New York and at Yale University, in the State of Connecticut. Bitnet interlinked large computers allowing people to communicate using terminals (monitor plus keyboard) connected to these machines, mainly in order to exchange e-mails. The aim was to connect academic institutions. In 1988, there were more than 1,400 universities and government agencies interconnected across 49 countries, including Brazil. In Europe, in 1982, Bitnet established a connection with the European Academic Research Network that was launched and maintained by IBM, and which linked 19 countries and more than 500 computers. Bitnet was the first Brazilian connection with an international network. A direct line was established in September 1988 between the National Scientific Computing Laboratory in Rio de Janeiro and the University of Maryland, in the United States. Ansp came on board the Bitnet in April 1989.

The experience of Ansp’s team allowed Fapesp, in addition to becoming the Brazilian connection with the internet, to transform itself into the technical center of the start of the Brazilian internet, including serving the National Teaching and Research Network (RNP) created by the Ministry of Science and Technology. The RNP was set up in 1989 and was getting ready to link itself to the web in 1990, which ended up happening in 1992, providing access to a number of the country’s research institutions. FAPESP’s computing group was set up when the Foundation decided to create a network in order to get onto the Bitnet, which had begun to work in 1981, developed by researchers at the University of the City of New York and at Yale University, in the State of Connecticut. Bitnet interlinked large computers allowing people to communicate using terminals (monitor plus keyboard) connected to these machines, mainly in order to exchange e-mails. The aim was to connect academic institutions. In 1988, there were more than 1,400 universities and government agencies interconnected across 49 countries, including Brazil. In Europe, in 1982, Bitnet established a connection with the European Academic Research Network that was launched and maintained by IBM, and which linked 19 countries and more than 500 computers. Bitnet was the first Brazilian connection with an international network. A direct line was established in September 1988 between the National Scientific Computing Laboratory in Rio de Janeiro and the University of Maryland, in the United States. Ansp came on board the Bitnet in April 1989.

Unlike the LNCC’s pioneering connection in Rio, in São Paulo it was necessary to set up a network that involving the University of São Paulo (USP), Campinas State University (Unicamp) and Paulista State University (Unesp), as well as the Institute of Technological Research (IPT). The need to join the Bitnet arose among the researchers and grant holders who returned from studying in the United States and Europe and who missed the electronic messages that were common in the academic world abroad. The ones who most requested electronic mail were the researchers at USP’s Physics Institute (IF). In 1987, Philippe Gouffon, who still teaches at IF, was concluding a post-doctoral study with a grant at Fermilab and already knew that the North American institution was willing to hook up with the Brazilian university by means of its network HEPNet (High Energy Physics Network). He presented the idea to IF Professor Carlos Escobar, one of the coordinators of FAPESP’s physics area. “I presented the idea to Oscar Sala, the Foundation’s president,” recalled Escobar. Both Sala, a physicist from IF, and professor Alberto Carvalho da Silva, a physician and physiologist who taught at USP’s Medical School and chaired the Foundation’s Technical Board, accepted the project, anticipating that the connection between USP’s High Energy Physics Laboratory and Fermilab would enable joint studies.

When it was being drawn up, in 1987, the network was given the abbreviation Span, an acronym for São Paulo Academic Network, but before it came into operation it changed its name. “We found out that Span was a Nasa (the North-American space agency) network: the Space Physics Analysis Network. So we changed it to Ansp, which involved turning Span around,” remembers Getschko. After being approved by the Foundation’s Governing Board, Ansp was able to connect to the Bitnet in 1988. It was very soon recognized as one of the global computer networks. It appears in a book with a strange name that is full of symbols, the same ones used for the addresses of the various technologies used up to that time: !%@:: A directory of electronic mail addressing & networks, by Donallyn Frey and Rick Adams, published in 1989 by the publishing house O’Reilly. “It was a type of global telephone directory that listed all the machines such as mainframes and PCs,” recalls Getschko. In addition to the recognition of Ansp, less than one year after it was put on air, the LNCC was also listed as representing Brazil. The book listed the Bitnet along with the other networks of computers and users. Flicking through its pages it is easy to see that the pages reserved for the internet still had only a few addresses, limited to a handful of North-American universities. Another interesting point is the proliferation of types of address. Not all of them used @, some used % or !. “We used to have very strange e-mails back at in those days, adding together these various networks,” remembers Getschko. One example is that of Hepnet which went like this: user name%fpsp.hepnet@lbl.gov, with fpsp, FAPESP, and the LBL (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory), being the networks’ link point in the United States.

When it was being drawn up, in 1987, the network was given the abbreviation Span, an acronym for São Paulo Academic Network, but before it came into operation it changed its name. “We found out that Span was a Nasa (the North-American space agency) network: the Space Physics Analysis Network. So we changed it to Ansp, which involved turning Span around,” remembers Getschko. After being approved by the Foundation’s Governing Board, Ansp was able to connect to the Bitnet in 1988. It was very soon recognized as one of the global computer networks. It appears in a book with a strange name that is full of symbols, the same ones used for the addresses of the various technologies used up to that time: !%@:: A directory of electronic mail addressing & networks, by Donallyn Frey and Rick Adams, published in 1989 by the publishing house O’Reilly. “It was a type of global telephone directory that listed all the machines such as mainframes and PCs,” recalls Getschko. In addition to the recognition of Ansp, less than one year after it was put on air, the LNCC was also listed as representing Brazil. The book listed the Bitnet along with the other networks of computers and users. Flicking through its pages it is easy to see that the pages reserved for the internet still had only a few addresses, limited to a handful of North-American universities. Another interesting point is the proliferation of types of address. Not all of them used @, some used % or !. “We used to have very strange e-mails back at in those days, adding together these various networks,” remembers Getschko. One example is that of Hepnet which went like this: user name%fpsp.hepnet@lbl.gov, with fpsp, FAPESP, and the LBL (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory), being the networks’ link point in the United States.

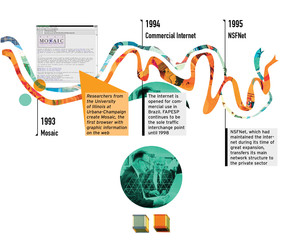

The internet’s story or its luck certainly took a positive turn with the possibility of global access to various kinds of information that arose thanks to the establishment of the world wide web, www, in 1991, in the United States. The internet grew and shortly thereafter, in 1994, began to break out of academia, becoming commercial as well. In Brazil, in 1995, the Ministry of Science and Technology and the Ministry of Communications set up the Internet Management Committee (CGI), comprised of representatives from the academic world, companies involved in the connections, providers and users. One of the CGI’s tasks was to handle the register of .br domain names, but this task was handed over by the committee to FAPESP, which had already been registering user names and handling the distribution of the IP numbers, which identify each computer. This links a name with a number that can be accessed by the network. “In 1989, we already had ?.br? registered for Brazil prior to the internet,” points out Getschko. This designation was assigned to FAPESP on April 18, 1989, by Paul Mockapetris and Jonathan Postel, of the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA). Concerning the names in the internet registers, Getschko and his team are unable to remember who was the first one to sign up in order to get their name on the web. Undoubtedly UOL, BOL and Estadão were among the first .com.br names. “The requests would arrive at FAPESP and Gomide would look at them one by one and say: Who are you? Are you a provider? OK you are not academic, so it’s going to .com.br. The procedure overseas was exactly the same and was also free of charge.” The first .com.br registrations were made manually by Gomide. “There was no need for any software. He examined them on a case-by-case basis and supplied the IP [Internet Protocol that identifies each computer] number.” Of course, this registration system was soon switched to one that used software, and the service began to be a paid one due to the costs involved.

FAPESP played a major role at the start of the internet as well as being the only traffic switching point (PTT) up until 1998, when various providers swapped traffic on the third floor of the FAPESP building in the Alto da Lapa neighborhood, in the city of São Paulo. PTT denotes a place that contains the routers that handle the switching between the internet’s autonomous systems. For example, it’s a place where an e-mail issued by the provider Terra that is addressed to the provider Gmail finds the route to the addressee. “Ansp was a free, neutral territory, where you could exchange traffic at will. Everybody managed to arrive with a telephone cable or an optic fiber on the third floor of the Foundation’s building, which therefore became a PTT,” explains Lopez. “However, one must clarify that there was no commercial traffic on the international line within the Ansp network, the companies simply used the place to exchange traffic,” he states. With the network’s growth, private PTTs were set up and FAPESP handed over all authority and power regarding the internet to CGI. With the total separation, Ansp returned to being an academic network like many others throughout the world. In order to supply the academic internet it maintains a PTTA, an academic traffic switching point in the city of Barueri, which is where the exchange of traffic between universities and research institutes takes place, in addition to having a connection with the commercial internet.

Republish