Lasar Segall Museum Collection – IBRAM (Brazilian Institute of Museums), Ministry of CultureNavio de emigrantes (Emigrant ship), by Lasar Segall (1939/41), oil with sand on canvas, 230 x 275 cmLasar Segall Museum Collection – IBRAM (Brazilian Institute of Museums), Ministry of Culture

When the Brazilian Ministry of External Relations opened its Historical Archives to the public in 1995, some of its documents revealed that the institution had taken part in the Estado Novo’s discriminatory, racist policy against foreigners, which put the Ministry – known as Itamaraty – in the uncomfortable position of the era’s “doorkeeper of Brazil.” Written by historian Fábio Koifman, of the Rural Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ), and recently published by Civilização Brasileira, the book Imigrante ideal (Ideal immigrant) exempts Itamaraty from all responsibility for this restrictive policy. “This is a historiographic error, one that overlooks the fact that from 1941 to 1945, the Visa Service was assigned to the Ministry of Justice, which really had the last word in accepting foreigners or not,” tells Koifman. This was the only time in the history of the Republic of Brazil that the task did not fall to Itamaraty.

The researcher says that his book is the first-ever analysis of the central roles played by the Ministry of Justice, by its head, jurist Francisco Campos (1891-1968), and by ministry secretary Ernani Reis (1905-1954), a bureaucrat who decided who could enter the country or not, based on his interpretation of the law. Reis’ suggestions were almost always accepted by the minister and were grounded in the selection of “desirable” immigrants, who fit the Vargas dictatorship’s project to “whiten” the Brazilian population. Blacks, Japanese, and Jews, as well as the elderly and disabled, did not meet the established standards and were rejected as “undesirable.”

Koifman’s research started when he came across Decree Law 3.175, of 1941, which shifted the power to grant visas from the Ministry of External Relations to the Ministry of Justice. But the Visa Service per se was not created by a presidential decree, even though it had its own official letterhead and such. It was never formally established and its funds came from other government bodies. “It was set up so its technical staff would be isolated and decisions would be made in a purely cold and technical fashion. They figured it would be easier to deny a visa than have to decide at the port,” the historian observes. “The whole process was never made public, and Francisco Campos used it when he explained to Vargas why Brazil should restrict immigration,” he reports.

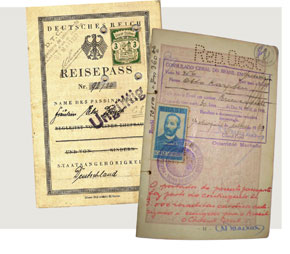

Collection of Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro1 Passport cancelled by the Nazis but accepted by Brazilian authorities 2 Otto Maria Carpeaux’s visa, included in the quota of Catholic JewsCollection of Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro

Itamaraty staff were ordered to provide the ministry with details about the person applying for a visa and await the minister’s decision to grant it or not. If a diplomat breached ministry guidelines, this would trigger a direct response from Vargas, who could open an administrative inquiry or even summarily dismiss the staff member. “This control stiffened when the situation in Europe became aggravated by the war and the rise of anti-Semitism in Germany. Jews and the politically persecuted began to flee Europe, pushing up demand at consulates. At that point, Brazil’s immigration policy turned against them.”

“At the outset of the Estado Novo, it fell to Itamaraty to manage visa policy, but this changed in 1941. The change reflected the debate within the Brazilian elite about the type of immigrant that would be ‘desirable’ for ‘perfecting’ the Brazilian people,” explains Koifman. Vargas was an avowed sympathizer with the ideals of eugenics. During a presidential campaign speech in 1930, he declared, “For years we thought about immigration in terms of economic aspects alone. Now it is opportune to heed the ethnic criterion.” In 1934, during Brazil’s Constituent Assembly, the well-organized eugenicist lobby managed to win the approval of articles based on racist theories. The target then was the Japanese. A system of quotas for each nationality was quietly put in place and manipulated to restrict the entrance of Orientals into Brazil.

“Brazil wasn’t the only one to adopt restrictive measures against immigrants and it even ‘took its time’ enacting them. Democracies like the United States and Canada were already doing so in the early 1920s,” the author points out. But once the process got underway, things went fast. Not satisfied with the laws of 1934, sectors of the Brazilian elite and intellectuals demanded greater government intervention and stricter selection as part of immigration policy. The result was Decree Law 3.010, of 1938, which required visa applicants to appear in person before the consul so the diplomat could see the candidate and report whether she or he was white, black, or had some physical disability. “Educated sectors of Brazilian society and many members of government, including Vargas, believed that the problem of Brazilian development was linked to the poor ethnic formation of its people. They thought that by bringing in ‘good’ immigrants – that is, whites who would mix with the non-white population – Brazil would be transformed into a more developed society within fifty years,” the researcher explains.

The ideal foreigner would be white, Catholic, and apolitical. Vargas’ personal preference was for the Portuguese. “Most of the immigrants coming from Portugal were of humble origins and had a limited education, and they were used to the Salazar dictatorship,” says Koifman. They were European but lacked “demoralizing ideas,” unlike the intellectualized groups from Germany, France, Austria, and other countries, who publicized their thoughts on Brazil’s flaws in newspapers and books. The Minister of Justice had a special abhorrence of foreign intellectuals and actually proposed that Brazil completely close its borders to immigration until the war in Europe ended, a measure Vargas rejected out of pragmatism.

“Brazil, which did not contribute to the making of these persecutions and hardships of life in Europe, cannot turn itself into a convenient guesthouse for a mass of refugees. We have no use for this white trash, this white scum that all civilized countries reject,” asserted Campos, who was also known as “Chico Ciência” (Chico Science). “One of the intellectual inspirers of the Estado Novo was influenced by Portuguese and Italian fascism and defended immigration laws grounded in American eugenic theories.” Going against the tide of enthusiasm over immigration, which had been in vogue in Brazil since the 19th century, Campos felt foreigners would only delay the country’s development, as “parasites” that contributed nothing to national progress. “The Jews, for example, engaged only in urban activities, in small commerce. The problem is that Campos and Reis soon realized that these were the same activities the Portuguese devoted themselves to, and they pointed this contradiction out to Vargas, much to the dictator’s irritation, since he wanted immigrants from Portugal,” says Koifman.

This upset Campos, whose ideology was not exempt from personal interests. He battled Oswaldo Aranha, then head of Itamaraty, for Vargas’ attention. To attack his rival, Campos tried to hammer home his claim that despite restrictions, foreigners were still getting into Brazil, thereby evincing Itamaraty’s ineptitude in managing the immigration question. He succeeded in convincing the dictator that his ideas were right and he won the power to choose the “desirables” and “undesirables” for the Visa Service. He failed, however, to impose the ideals of eugenics he so admired and was forced to “tropicalize” them. “The races admired by the Americans were a minority in a country composed mostly of groups deemed ‘inferior’,” the historian points out. This prompted Campos to concentrate his fight on “unmixable” immigrants who supposedly displayed a low propensity for intermarriage – which included the Jews – and thus were not suitable for a whitening project that relied on miscegenation.

“But restrictions on the entrance of Jews – a recurring theme in studies of immigration policy under the Estado Novo – must be seen as part of a broader context, in which various other groups were likewise classed as ‘undesirable’. If being a Jew made it harder to get a visa, proving that you were not a Jew was no guarantee that you’d get one,” Koifman observes. For the researcher, the anti-Semitism of a fascist like Campos was not analogous to the racism of the Nazis. “After the communist uprising of 1935, known as the Intentona Comunista, the government adopted a generic view of Jews that associated them with communism – anti-Semitism grounded in politics, which was shared by Vargas,” the researcher says. In the words of Campos: “The Jews have taken advantage of the carelessness of the Brazilian authorities. Although Brazil is not fascist or national-socialist, the truth is that these communizing, socialist, leftist, and liberal elements adhere to a system that is far from appropriate for us.”

While Koifman does not deny the anti-Semitism of individual members of the Brazilian government and society, he believes that the most important criterion adopted – alongside apprehension about the “red threat” – was the immigrants’ alleged ability, or not, to “mix.” “The concern was over the potential union of white Europeans with the descendants of Africans and indigenes, which was prerequisite to achieving the ‘perfection’ of future generations,” he says. “The Estado Novo did not want to reproduce racism, then so much in fashion in the United States and Europe. Segregation was to be avoided at all costs, as it would obstruct miscegenation, the driving force behind whitening,” he explains. Vargas would not tolerate racism against ethnic groups within Brazil.

This caution also had to do with maintaining a good international image, especially to please the United States, whose racial policy when it came to others did not reflect its own internal reality. “Being accused of active racism in the 1930s and 1940s put any nation, diplomat, or intellectual in the awkward position of alignment with Nazi Germany’s policy of exclusion,” explains historian Maria Luiza Tucci Carneiro, of the University of São Paulo (USP) and author of the classic study Antissemitismo na era Vargas (Anti-Semitism in the Vargas era; 1987). “Still, the Estado Novo, through its Ministry of Justice and nationalist policy, would not abide any fissures, and it combated migrant groups that were seen as elements of ‘erosion’. The regime’s ideal was homogeneity, to the detriment of diversity,” she points out.

Ambiguities

The Brazilianist Jeffrey Lesser, of Emory University and author of Welcoming the Undesirables: Brazil and the Jewish Question (1995), believes that one has to be cautious about relying only on official documents from either Itamaraty or the Ministry of Justice when portraying the era’s immigration policies. “Writings reveal the ambiguities that governed this policy. For example, how does one explain the significant number of Jews who entered shortly after the restrictive decrees, or the expressive absorption of these groups, along with Arabs and Japanese, into Brazilian society in the late 1930s?” he asks. In his opinion, there was major inconsistency between discourse and practice, producing curious paradoxes. “Immigrants turned the eugenic discourse about whitening, which discriminated against them, in favor of their own interests and managed to win a place in society. They realized that being white in Brazil was better than being black, and they took up the eugenic rhetoric too.”

“There are a series of police reports about fights between foreigners and blacks. Poor immigrants didn’t want to be seen as the new slaves, and they affirmed their superiority by attacking blacks,” observes Lesser. If documents tell one story, the xenophobic movement did not work as intended in the day-to-day world of the Estado Novo. The Brazilianist does not deny the Brazilian elites’ discourse against immigration or their anti-Semitism but as he studied real cases, he saw that the government was more flexible in its actions than indicated by the harsh words on official paper. “One good example is that before the Brazilian government enacted the laws that would restrict the entrance of Japanese, in 1934, it advised Japan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs. A Brazilian diplomat told the Japanese minister what was going to happen and appeased him by promising that Orientals would still be able to enter Brazil, using quotas for countries like Finland, which went practically unused,” he says. Lesser compiled other cases where the famous Brazilian knack known as jeitinho was used to find a way around legal barriers.

To the American, the most astonishing example of this flexibility, which we don’t read about in the official archives, is Itamaraty’s secret cooptation of staff at the German Consulate to get them to falsify the consul’s signature, clearing immigrants to enter Brazil. “At a lecture, I called the consul a Nazi, and some people in the audience were indignant, displaying visas signed by the consul, who they called a hero, with no clue they were falsified,” he reports.

Koifman respects Lesser’s hypothesis about “negotiating” the laws but he argues that Visa Service documents do not support this view. “The law was indeed applied, and any malleability depended upon the immigrant’s origin. Just look at the little-known question of the Swedish: they had a representative community in the country and were not much interested in immigrating to Brazil, but the Visa Service was especially interested in their coming,” he observes.

This is evident in the case of a Swedish gentleman who fell sick during a trip, got off his ship to be treated, and, when he realized it, found that a visa was being arranged for him – even though he did not want to stay in Brazil. “On the other hand, many people who were wholly qualified to emigrate, who had the necessary papers, ran into delays and rulings that hampered their entrance if they were not an ‘ideal immigrant’. This shows how the criteria were based on the banner of eugenics,” he explains. Koifman believes that this debunks the nationalist discourse and alleged flexibility of the laws, reducing them to their true dimension: the utopia of ethnic “perfection.”

Republish