Two scientific studies are beginning to shed light on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines among the Brazilian population. The first, carried out in Serrana, in the Ribeirão Preto region of São Paulo, released its preliminary results at the end of May, providing good news: after 75% of the adult population was fully vaccinated with CoronaVac, developed by Chinese pharmaceutical company Sinovac Biotech and produced in Brazil by the Butantan Institute, the epidemic showed signs of being under control. In Botucatu, also in the interior of São Paulo State, the study is at an earlier stage. In May, almost 100% of the target audience (residents aged 18–60) received their first dose of Covishield, developed by the University of Oxford, UK, in partnership with the Swedish-British laboratory AstraZeneca. The 74,000 participants will be given a second dose on August 8 and 9. The final results of the Botucatu study are scheduled to be released in February 2022.

“Effectiveness is the name given to how well a vaccine or drug works in real life. The clinical trials that led to their approval for use tell us the efficacy—how well the vaccine works individually—but there are limits to the knowledge they provide,” explains epidemiologist Carlos Magno Fortaleza, from the School of Medicine at São Paulo State University (UNESP), Botucatu campus, who designed and is leading the study. “Effectiveness studies determine the protection afforded to smaller subgroups, such as the elderly or patients with heart disease and diabetes, and analyze the indirect protection for those who are not vaccinated.” These studies are expected to validate the findings of the efficacy trials, but there can be surprises—the effectiveness may be higher or lower than expected.

The Serrana study, named Project S and funded and run by the Butantan Institute with additional funding from FAPESP, vaccinated 27,160 of the municipality’s 45,644 residents with two doses of CoronaVac over eight weeks, between February 14 and April 10. The equivalent to 96% of the target audience (inhabitants over 18 years of age) were immunized. The town was divided into 25 subareas, forming four large population groups that were given the vaccine in successive weeks. According to the researchers, the spread of the virus was under control after the third group had been given their second dose, suggesting that immunization of about 75% of the target population—equivalent to 45% of the total population—was enough to stop the pandemic.

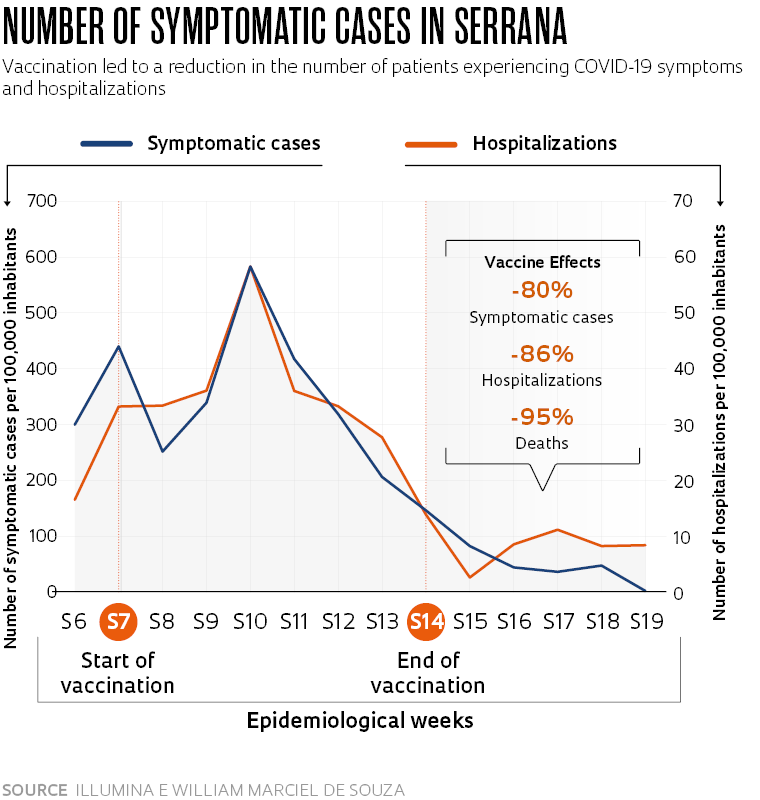

The major milestone used by the study was epidemiological week 14, from April 4 to 10, when all groups had been given both doses of the vaccine. “When comparing the periods before and after immunization was completed at week 14, we found an overall reduction in symptomatic cases of 80%, regardless of whether people had taken the vaccine or not,” highlights infectious disease specialist Ricardo Palacios, medical director of clinical research at the Butantan Institute and one of the researchers behind Project S. He added that overall, hospitalizations fell by 86% and deaths fell by 95% (see infographic).

“This reflects the direct effect of people who were vaccinated, thus protecting themselves, and the indirect effect of reduced transmission of the virus due to the high number of vaccinated people in the community.” The synchronization between the drop in symptomatic cases and hospitalizations across vaccinated and unvaccinated groups, according to Palacios, is a result of this indirect effect of immunization. “This is evidence of indirect protection, also known as herd immunity.”

The number of symptomatic cases and hospitalizations among people under 18 years of age also decreased, even though nobody in this age group was vaccinated. “This data is important, because for other vaccinations implemented by age group, one of the possible effects is that the infection gets pushed toward the groups that are not vaccinated. What we saw was a protective effect,” says Palacios, emphasizing the importance of this information in discussions about resuming face-to-face schooling in the country. Mass immunization also led to a fall in the number of hospitalizations among the elderly (over 70 years old). “The vaccine protected people who were not vaccinated for whatever reason, even in the highest age groups,” said the director of Butantan.

The public were commended for their willingness to participate in the study. “Few vaccination programs in the world have such significant figures [of vaccination coverage]. It shows that the public wants to be vaccinated,” says physician Marcos de Carvalho Borges, lead researcher of Project S and a professor at the Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine (FMRP) of the University of São Paulo (USP). Infectious disease specialist Esper Kallás, from the Department of Infectious and Parasitic Diseases at USP’s School of Medicine (FM) in São Paulo, believes the support from the local community has been extraordinary. “Looking around [Serrana] is irrefutable evidence of the effect of the vaccine. It shows its effectiveness, safety, and performance against the variants,” says Kallás.

The researchers compared Serrana with 16 nearby municipalities, including Brodowski, Jardinópolis, and Cravinhos. “We see the result of an uncontrolled epidemic in the region. In general, the microregion of Ribeirão Preto is suffering enormously, but this does not true in Serrana,” highlights Palacios.

In total, 54,882 doses of CoronaVac were administered, all donated by Sinovac. Sixty-seven serious adverse events were recorded, but none were related to the vaccine. Anything that happens to a person after they have been immunized is recorded as an adverse event, which can be classified as mild, moderate, severe, or lethal. “For example, if somebody is vaccinated and two weeks later is involved in a car accident, this is a serious adverse event, but it has no causal relationship with the vaccine,” says Borges.

When the results were published at the end of May, eight COVID-19 deaths had been recorded among those vaccinated. Seven of them, however, had only received the first dose. From 15 days after the second dose, no deaths were recorded and only two people were hospitalized due to COVID-19. An immunological survey of the population carried out before the study began revealed that 25.7% of residents had already been exposed to the virus.

The situation in Ribeirão Preto remained critical in early June and monitoring of Serrana is ongoing—the study is planned to last a year. “We are showing, at least for the time being, that vaccination is capable of controlling the epidemic,” says Borges. According to him, the research is intended to reveal how long the immunity conferred by the vaccine lasts. Genetic sequencing of samples from patients who test positive will also ensure quick detection of possible new mutations in the virus.

The primary results have been presented to the media and the general public, while the researchers continue to analyze the data generated by the study for a scientific article. “What we have disclosed so far was a more descriptive analysis, such as the effectiveness. Now we need to create a mathematical model to describe our findings. We hope that this will be ready in the next few weeks,” Borges told Pesquisa FAPESP.

Although Serrana continues to follow the rules established in São Paulo’s State COVID-19 Plan, Borges believes restrictions in the municipality may be lifted earlier than in other places. “It is only natural that some will activities return to normality sooner in Serrana, a higher percentage of students at school maybe, or allowing events to be held. It makes no sense for a town not to lift restrictions when almost everyone is vaccinated and the pandemic is under control. But this would require central coordination and any easing to be linked to the State Plan.”

The study in Botucatu, which used the Covishield vaccine produced by the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), is a few steps behind Serrana. Those involved in the research are currently currently monitoring cases while preparing for a new round of immunization, with the target audience set to receive their second doses over two days in August. In the first phase, 67,000 people were vaccinated in a single day on May 16. Another 7,000 received their first dose the following week. People aged over 60 and health professionals had already been vaccinated under the National Immunization Program (PNI). Pregnant women and new mothers are not participating in the study.

“Everyone on the electoral register with proof of address was vaccinated in a single day. Other people, such as students at UNESP’s Botucatu campus or people who have lived in the town for years and can prove it but are not on the electoral register, were vaccinated on other days. These cases were analyzed with the help of the Brazilian Bar Association and the Public Prosecutor’s Office to ensure they really were residents,” says Fortaleza. “This was important because the risk of people from elsewhere trying to fraudulently gain access to the program was high. I can’t say that we avoided it completely, but we greatly reduced the likelihood with this strategy.”

People were vaccinated in their electoral zones and at defined times according to their age, in order to reduce crowding. About 2,500 people volunteered to work as administrative staff and vaccinators. “We were supported by students from the School of Medicine, health professionals, and people from other areas who performed administrative duties. The project sparked great public enthusiasm,” says Fortaleza.

The study is being led by UNESP with funding from the local government, the Brazilian Ministry of Health, which donated the FIOCRUZ vaccines and around R$10 million to purchase reagents and genetic sequencing machines, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. It is being carried out in partnership with the University of Oxford and the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). Two molecular biology labs at UNESP have been sequencing the genomes of virus samples from positive cases in the town and 12 other smaller municipalities in the region, which will serve as controls. “It is thanks to the technological park, built up over the years with funding from FAPESP, that we are able to take on this challenge,” says Fortaleza.

In mid-June, the team was still awaiting funds promised by the Ministry of Health for the genome sequencing, but of the samples already sequenced, most patients had the P1 variant, first identified in Manaus and renamed as the gamma variant. The same was true in Serrana.

Although it used a different methodology to Project S, which opted for a staggered approach, with vaccination taking place over eight weeks, Fortaleza does not hide his admiration for the Butantan Institute’s work. “Serrana was an inspiration. But we did not base our research on any previous experience. We opted for a different, independent methodology,” stresses the researcher, highlighting the decision to vaccinate the target audience all at once, among other differences.

With extensive experience of vaccination campaigns in Brazil, phyisician José Cassio de Moraes, from the Santa Casa de Sao Paulo School of Medical Sciences, is following the Brazilian effectiveness studies with interest, as well as those carried out in other countries, such as Uruguay, Israel, and England. “The Serrana study is important and promising, but so far we only have early data,” says Moraes, a member of the Epidemiology Commission of the Brazilian Association of Collective Health (ABRASCO).

He believes the research has to answer the question of whether the variants circulating in Brazil are capable of reducing the protection conferred by the vaccine. This is crucial information, especially in Brazil, where vaccination is progressing very slowly. “The PNI easily has the capacity to vaccinate 2 million people a day. We have 36,000 vaccination centers. That allows for 10 million doses a week, or 50 million a month. In six or seven months, the entire population of Brazil could be given two doses,” he says. “But to do that, we need to actually have the vaccine. And we started the process late,” he points out.

Project

Development of a COVID-19 vaccine (nº 20/10127-1); Grant Mechanism Research in Public Policy; Principal Investigator Dimas Tadeu Covas (Butantan Institute); Investment R$32,501,477.

Republish