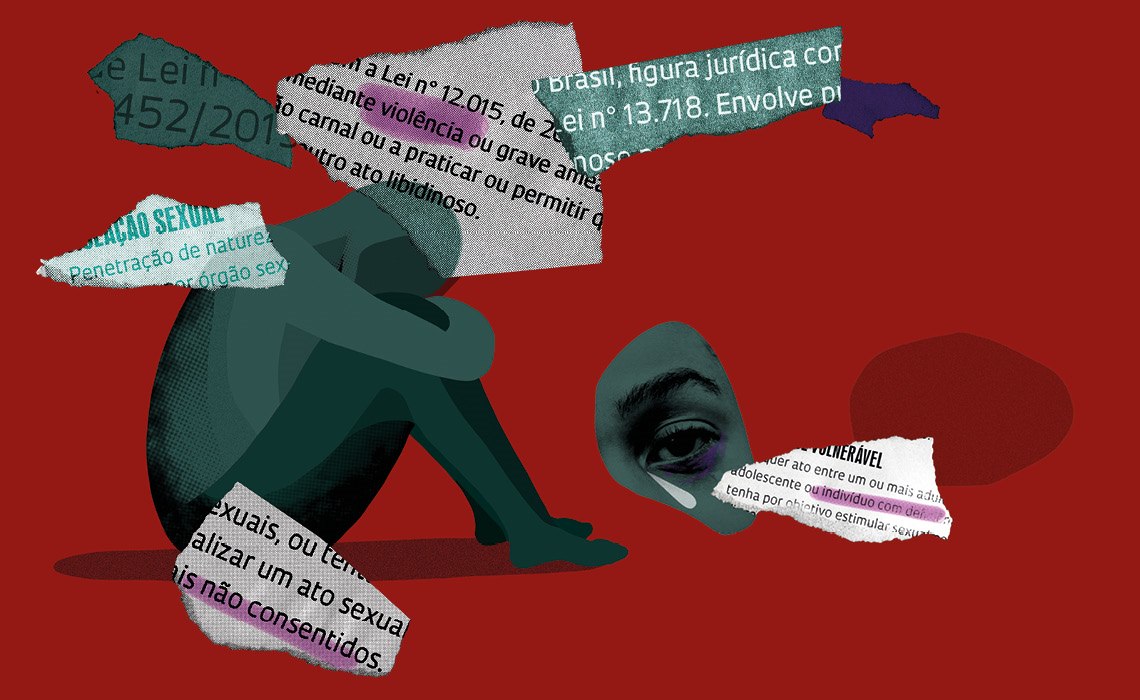

In dialogue with gender studies and the feminist movement, Brazilian legislation has invested in legal concepts to punish different types of sexual violence. In the last decade, for example, rape ceased to be considered a crime against societal customs and is now classified as a violation of an individual’s sexual dignity. At the same time, child abuse has begun to be punished more severely. Despite these advances, however, researchers have identified obstacles to application of the law and highlight the need to develop public policies capable of supporting the fight against sexual violence.

– Sexual violence causes psychological distress and results in inflammation that can accelerate aging

Law 12.015 of 2009 defines rape as “forcing a person, through violence or serious threat, to have sexual intercourse, perform a sexual act, or allow a sexual act to be performed on them,” punishable by up to 10 years in prison (see glossary). Between 2012 and 2021, the police recorded 583,000 rapes in Brazil, according to the Brazilian Public Security Annual Report 2022 by the Brazilian Public Security Forum (FBSP). In 2021, there were 66,000 police reports of this crime, representing a growth of 4.2% over 2020. Nine out of 10 victims were aged under 30 when they were raped, while children under 13—classified as vulnerable by law—accounted for 61.3% of all victims.

Mariângela Magalhães Gomes of the School of Law at the University of São Paulo (FD-USP) explains that Brazilian legislation has improved in recent years, aiming to establish adequate sentences for the different types of crime relating to sexual violence. Portuguese legislation of Spanish origin—named the Philippine Ordinances after King Philip II of Spain—was used in Brazil from 1603 until the 1800s, making no mention of rape, but criminalizing “individuals who entered family homes and slept with virgins, widows, or white slaves.” “In these circumstances, a convicted man would serve a prison sentence and be obliged to pay compensation to the family, since a rape victim who was no longer a virgin would not be able to marry. In other words, according to the law, the crime of rape primarily harmed the woman’s marriage value,” says Gomes. If the violator was willing to marry the victim and the proposal was accepted, however, the legislation considered the damage repaired and the conviction was annulled.

The term “rape” was first incorporated into Brazilian legislation in 1830 with the institution of the Criminal Code of the Portuguese Empire. The crime was characterized as forced penetration of a woman by a man. “The law’s position was that the worst damage caused by rape was the loss of female virginity and not the violence against a woman, based on the idea that not being a virgin meant a woman was no longer fit for marriage. It also considered that the crime was more serious when committed against an ‘honest woman’ than against prostitutes,” she points out. The penalty for violating an “honest woman” was 3–12 years in prison. If the victim was a prostitute, the sentence would not exceed 24 months.

In 1890, with the adoption of the Penal Code of the Brazilian Republic, the term “rape” was replaced by “carnal violence” in the list of crimes against family honor and a source of social shame. The idea that rape is a violation of society’s customs and values remained in the current Penal Code, in force since 1940. “Following the perspective of the preceding penal codes, this legislation sought to protect the reputation of women. Sexual freedom was not seen as a right,” says the jurist.

Laws evolve, but the legal system is slow to change their applications

At the time defined as forced sexual intercourse between a man and a woman, the 1940 legislation separately defined the crimes of rape and indecent assault, the latter of which included other forms of sexual violence against both men and women. Penalties for rape ranged from three to eight years in prison, while they ranged from two to seven years for indecent assault. “Although this code does not explicitly mention the term ‘honest woman’ with respect to rape, in jurisprudence, the fact that the victim was an unmarried virgin was a central element in the conviction of aggressors until the early 2000s,” says Gomes. She highlights that although the 1940 Code did not extinguish sentences when aggressors married their victims, this clause was reinserted in 1977 and the rule came back into effect. Article 59 was added to Brazil’s Penal Code in 1984, listing criteria for judges to follow when determining sentences. “One of these guidelines is that they should consider whether the victim’s behavior may have encouraged the crime,” highlights Gomes, recalling that Law No. 8.072, enacted in 1990, made sentencing equivalent for rape and indecent assault.

Guita Grin Debert, an anthropologist from the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), studied rape trials in the 1990s and found that just as with cases of homicide, rape trials centered around the victim’s behavior. Debert recalls that it was only when Law No. 11,106 was passed in 2005 that the term “honest woman” was removed from the Penal Code and the determination that rapists would not be punished if they married their victim was removed. “Even so, to this day many judges still take a woman’s reputation into account before determining a sentence,” says Debert. Four years later, when Law No. 12.015 was enacted, rape ceased to be classified as a crime against societal customs and became a crime against sexual dignity. “It was then that the law stopped differentiating between rape and indecent assault. Rape is the most serious type of sexual violence,” stresses the anthropologist.

In July, the Committee on Constitutional, Justice, and Citizenship Affairs (CCJ) approved a bill authored by Senator Zenaide Maia prohibiting use of the argument of “legitimate defense of honor” to acquit people accused of femicide, in addition to excluding mitigating factors related to violent emotions and the defense of moral or social values in domestic and family violence trials. The bill is waiting to be voted on in the House of Representatives. Despite the legal basis for strict punishments for the crime of rape, both Debert and Gomes agree that the country lacks public policies capable of effectively addressing the problem. “It is wrong to rely solely on penal legislation as the solution to sexual crimes. We must invest in social approaches, teaching society to respect women,” emphasizes the USP jurist.

In a similar vein, anthropologist Heloisa Buarque de Almeida, from the same institution, points out that only 10% of rapes are actually reported, according to FBSP data. One of the reasons for this is the fact that eight out of 10 rape cases recorded in 2021 were committed by people known to the victims, according to the Brazilian Public Security Annual Report 2022. “The boundaries between sexual assault and rape are blurred, and victims often do not understand the violence they have suffered and fear retaliation, embarrassment, or being revictimized. The result is that they do not report the crime to the authorities,” she explains, noting that the perception of what is considered violence changes over time. “In the past, whistling at someone in the street was considered a compliment. Today, depending on the context, it can be classified as sexual harassment,” she highlights. And when they are reported, crimes of sexual violence rarely result in convictions.

Another challenge involves jurisprudence, which often follows guidelines based on legal precedents. “The laws have evolved, but the legal system is slow to change the way it applies them,” says Almeida. Aware of this situation and aiming to raise awareness in the Judicial Branch, the National Council of Justice (CNJ) published a document in 2021 containing guidelines for judges making decisions related to gender issues. The report draws attention to the fact that rape primarily affects women and girls, and is mostly committed by men. In other words, the crime reflects aspects of societies marked by gender asymmetry. In addition, since the crime is usually committed in private places, the document warns about the difficulties of obtaining evidence and witnesses, advising that magistrates should place more weight on the victim’s testimony, rather than questioning the alleged lack of evidence. The CNJ argues that gender must be used as a lens for interpreting events, identifying the context behind the conflict, and ensuring that all parties involved in the legal process understand what is being discussed. It also recommends that judges assess the need to establish protective measures to immediately break the cycle of violence affecting the victim, as well as avoid asking questions that might cause them to re-live traumatic moments.

Sexual violence

Nonconsensual sexual acts, attempted sexual acts, comments, or advances. Includes any sexual action taken by a person in a position of power or who coerces another person to engage in sexual or sexualized behavior against their will through physical force, psychological influence, or the use of weapons and drugs. Covers all forms of rape: individual, group, corrective, against adults or children. Also includes sexual harassment, sexual assault, forced prostitution, sexual exploitation, revenge pornography, and the sending of unsolicited sexual photos and content online.

Sexual violation

Nonconsensual sexual penetration of a victim’s body by any part of the attacker’s body or by an object, through the use of force or threats/coercion. Rape is considered a form of sexual violation.

Rape

Defined by Article 213 of the Brazilian Penal Code as “forcing a person, through violence or serious threat, to have sexual intercourse, perform a sexual act, or allow a sexual act to be performed on them.”

Rape of a vulnerable person

Any act performed against a child or mentally handicapped person with the objective of sexual stimulation, or use of a child or mentally handicapped person to obtain sexual satisfaction in any way. Vulnerable individuals are not independent or mature enough to understand or consent to sexual activities.

Sexual assault

Defined in 2017 through Article 215-A of the Brazilian Penal Code as “performing a sexual act against someone, without their consent, with the objective of sexually satisfying the person performing the act or a third party.” Situations in which a man ejaculates on a woman on public transport, for example, fall under this criminal behavior.

Corrective rape

Cases in which the crime of rape is intended to alter the sexual or social behavior of the victim. Bill 452/2019 proposes adding cases of rape used to “correct” the sexual orientation of lesbian women or “control the fidelity” of a spouse to the Brazilian Penal Code under this definition.

Sources World Health Organization, Brazilian Public Security Forum, Law No. 12.015/2009, and National Council of Justice

Projects

1. Meanings of sexual violence: The media and the public dispute for the construction of rights (nº 17/02720-1); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Heloisa Buarque de Almeida (USP); Investment R$33,481.14.

2. Meanings of sexual violence: The media and the public dispute for the construction of rights (nº 18/10403-9); Grant Mechanism Fellowship abroad; Principal Investigator Heloisa Buarque de Almeida (USP); Investment R$100,102.68.

Scientific articles

ALMEIDA, H. B. From shame to visibility: Hashtag feminism and sexual violence in Brazil. Sexualidad, salud y sociedad. vol. 33. 2019.

GOMES, M. G. M. Duas décadas de relevantes mudanças na proteção dada à mulher pelo direito penal brasileiro. Revista da Faculdade de Direito (USP). vol. 115, pp. 141–63. 2020.

Book chapter

ALMEIDA, H. B. A visibilidade da categoria assédio sexual nas universidades. In: ALMEIDA, T. M. C. & ZANELLO, V. (orgs.). Panoramas da violência contra mulheres nas universidades brasileiras e latino-americanas. Brasília: OAB Editora, pp. 195–220. 2022.

Reports

Protocolo para julgamento com perspectiva de gênero. Conselho Nacional de Justiça, 2021.

Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública. Fórum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública, 2022.