With the number of Covid-19 infections and deaths growing daily, Brazil has gradually come to a stop as the population attempts to contain the spread of the virus. Having witnessed other countries dealing with the impacts of the pandemic, which started in China in December 2019 and arrived in Brazil in February 2020, the potential gravity of the situation is all too clear. By April 1, the SARS-CoV-2 virus had spread to 180 countries, with 926,000 reported cases and 46,000 deaths. In Brazil, there have been 240 deaths so far, and the number of cases—currently at 6,800—is doubling every 1–2 days and multiplying tenfold every week. The number is expected to increase even more rapidly from the end of April onward, when the temperature drops and respiratory diseases like Covid-19 spread more easily. The Pesquisa FAPESP website has a selection of maps showing the latest number of confirmed cases and deaths in Brazil and worldwide.

The first deaths in Brazil, recorded in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro in March, led to rising apprehension about how the epidemic would spread around the country. Specialists from public health agencies and universities predict that the virus will infect tens of thousands of people in Brazil, with thousands of deaths as a result. The current global mortality rate, on average, is 3.4% of infected people, but this figure varies widely between countries—at 0.2% in Germany and Norway, 2.2% in France, 3.9% in China, 6.1% in Iran and 7.9% in Italy—depending on the health and age of those infected and their access to healthcare.

In the city of São Paulo, which has more than 12 million inhabitants, the streets are unrecognizable in the wake of SARS-CoV-2, with gridlock giving way to smoothly flowing traffic. In response to state government guidelines, schools, universities, museums, cultural centers, and shopping malls have all closed. Stores and public agencies have reduced their operating hours, while many companies have told their employees to work from home. Many other Brazilian cities followed suit, implementing measures similar to those already taken in other countries to restrict the circulation of people in an attempt to stop transmission of the virus.

The spread of Covid-19 can be compared to that of the Spanish flu, caused by a lethal strain of the influenza A virus, of the H1N1 subtype. Between 1918 and 1920, the Spanish flu spread around the world with devastating consequences: it infected around 500 million people—roughly one-third of the global population at the time—and killed between 25 and 50 million people, most aged 20 to 40 years old. In São Paulo, the epidemic killed 5,300 people, equivalent to 1% of the city’s population, within just a few months. Bodies accumulated on the streets waiting to be collected. In Rio de Janeiro, the situation was much the same. In 2009, a new pandemic (an epidemic that occurs worldwide) involving the H1N1 virus spread across the planet. Known as swine flu due to its origin in pigs, it was the first pandemic of the twenty-first century. It affected somewhere between 700 million and 1.4 billion people, causing 150,000–580,000 deaths. In Brazil, 58,000 individuals were infected and 2,100 died.

In March, Italy, Spain, and the USA suffered the most dramatic impacts of the coronavirus, with rapidly rising death tolls. China announced a drop in the number of cases and an end to local transmission, which allowed them to reopen factories and resume the many services that had been suspended as the virus spread. Other countries, meanwhile, were facing the arrival and spread of SARS-CoV-2, or were already feeling its economic effects: most businesses have closed while customers take refuge at home, stock markets have fallen, including Brazil’s, and production at companies that depend on parts imported from China has stopped. US President Donald Trump cited an increasingly likely recession when announcing an unprecedented $2 trillion set of economic measures to be imposed in the country.

Antonio Masiello / Getty Images

Rome, March 17, 2020: medical team transports a Covid-19 patient to hospital on a sealed stretcherAntonio Masiello / Getty ImagesHere in Brazil, the government announced emergency measures to reduce the economic impact of the epidemic, with the release of R$40 billion in aid over the next two months to help the most vulnerable sectors, such as informal workers (38 million people, 41% of the nation’s workforce) and small businesses. The federal government and the São Paulo state government have both declared a state of emergency, which should allow for increases in health spending and help reduce the economic impact of the pandemic in Brazil. The Central Bank estimated that instead of growing by 1.9% as forecast, the economy will shrink by between 3.2% and 7.7% because of the crisis.

Closing schools and stores, social distancing, encouraging people to stay at home, and quarantining those infected can all help to delay transmission and reduce the number of people requiring hospitalization at the same time, but they do not completely stop the virus from circulating, according to a report published in March by British epidemiologist Neil Ferguson of Imperial College London.

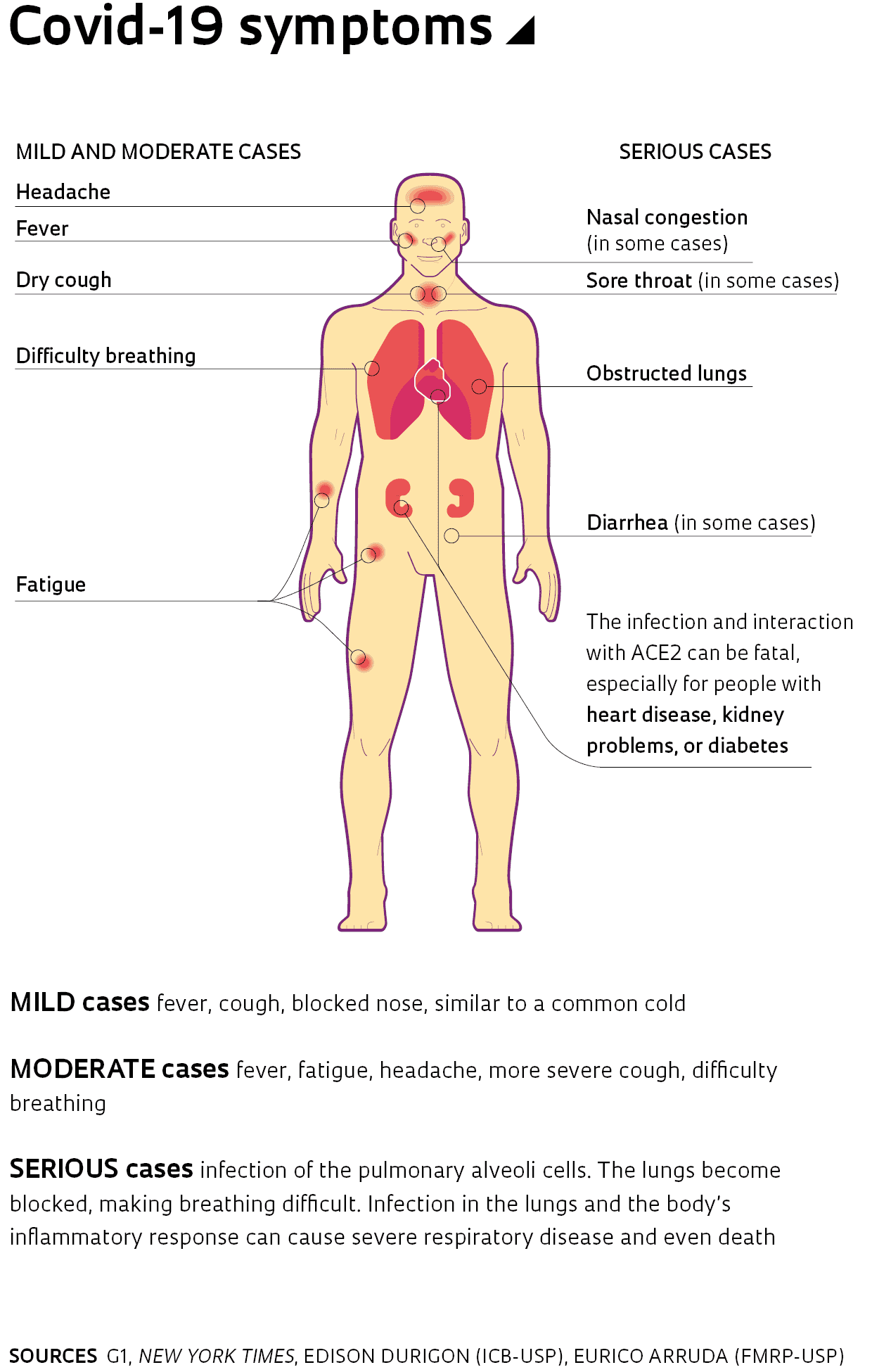

As more cities in Brazil decided to close schools, 41 million children aged 4–17 years have stopped going to classes and now spend their days at home with their parents. Because children can carry and transmit the virus even if they have only mild symptoms, leaving them with grandparents was not recommended, due to how lethal SARS-CoV-2 has proven in people over 60, especially those with cardiovascular disease, kidney problems, diabetes, or cancer.

The virus has changed people’s habits and given rise to the concept of social distancing, with recommendations including not to hug or kiss when greeting people, and to always stay at least 2 meters from others. “Social isolation measures have halved the virus’s contagion rate,” says infectious disease physician Júlio Croda, a researcher at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (FIOCRUZ), professor at the Federal University of Mato Grosso do Sul (UFMS), and member of the São Paulo State Coronavirus Contingency Committee, based on a study in its final stages at the end of March. The research indicates that the transmission rate has dropped from 4 to 2. According to Croda, the social isolation rate, based on data from cellphone operators, rose from 15% before the first Covid-19 case was recorded in Brazil to 60% at the end of March.

Although necessary to prevent the spread of the disease, this measure can have unwanted psychological effects. Pharmacist Poliana Carvalho, a researcher at the ABC Medical School, noted that depression, panic attacks, psychotic episodes, and delirium increased during the early phases of the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic in 2002, which saw social isolation implemented as a means of stopping the virus. Caused by another variety of coronavirus that also emerged in China, SARS infected around 8,000 people and killed approximately 800 in 26 countries. Brazil was not affected. Even with the potential drawbacks, it is essential to maintain social isolation, as recommended by infectologists, to avoid an exponential increase in the number of cases and consequent collapse of healthcare systems (see report).

In a study published in the journal Psychiatry Research in April, Carvalho commented that the symptoms of the virus, such as fever, difficulty breathing, and a cough, added to insomnia and other side effects of drugs used against the disease, such as corticosteroids, can cause anxiety and aggravate mental illnesses. At a press conference in early March, when asked how to stop the contagious fear of epidemics, infectious disease specialist David Uip, coordinator of the São Paulo State Coronavirus Contingency Center—now in isolation having tested positive for SARS-CoV-2—replied to the media: “We rely on you.” “It’s very difficult,” says epidemiologist Eduardo Massad, a professor at the Getulio Vargas Foundation (FGV) in Rio de Janeiro.

In addition to encouraging social distancing, the Ministry of Health brought forward the start of the annual flu vaccination campaign for the elderly and health professionals—reducing the number of common flu patients makes it easier to diagnose coronavirus—and announced the possibility of increasing the number of beds in hospital intensive care units to prevent shortages if the number of serious cases grows beyond normal capacity.