The Amazon is a land of extremes. Its massive size and natural riches contrast with the economic, educational, and social needs of its populace. The 771 municipalities of the nine states that make up the Brazilian Legal Amazon occupy 5.22 million square kilometers (km2), or 522 million hectares. This region corresponds to 61% of Brazil’s land area, and is equivalent in size to all 28 countries of the European Union plus Egypt, or more than half of Canada, the second-largest country in the world. One-fifth of the Cerrado (wooded savanna) and two-thirds of the Amazon Rainforest, the largest contiguous rainforest in the world, are in Brazil’s Legal Amazon. This is also where most of Brazil’s reserves of iron, tin, aluminum, nickel, copper, manganese, niobium, gold, natural gas, and oil are located.

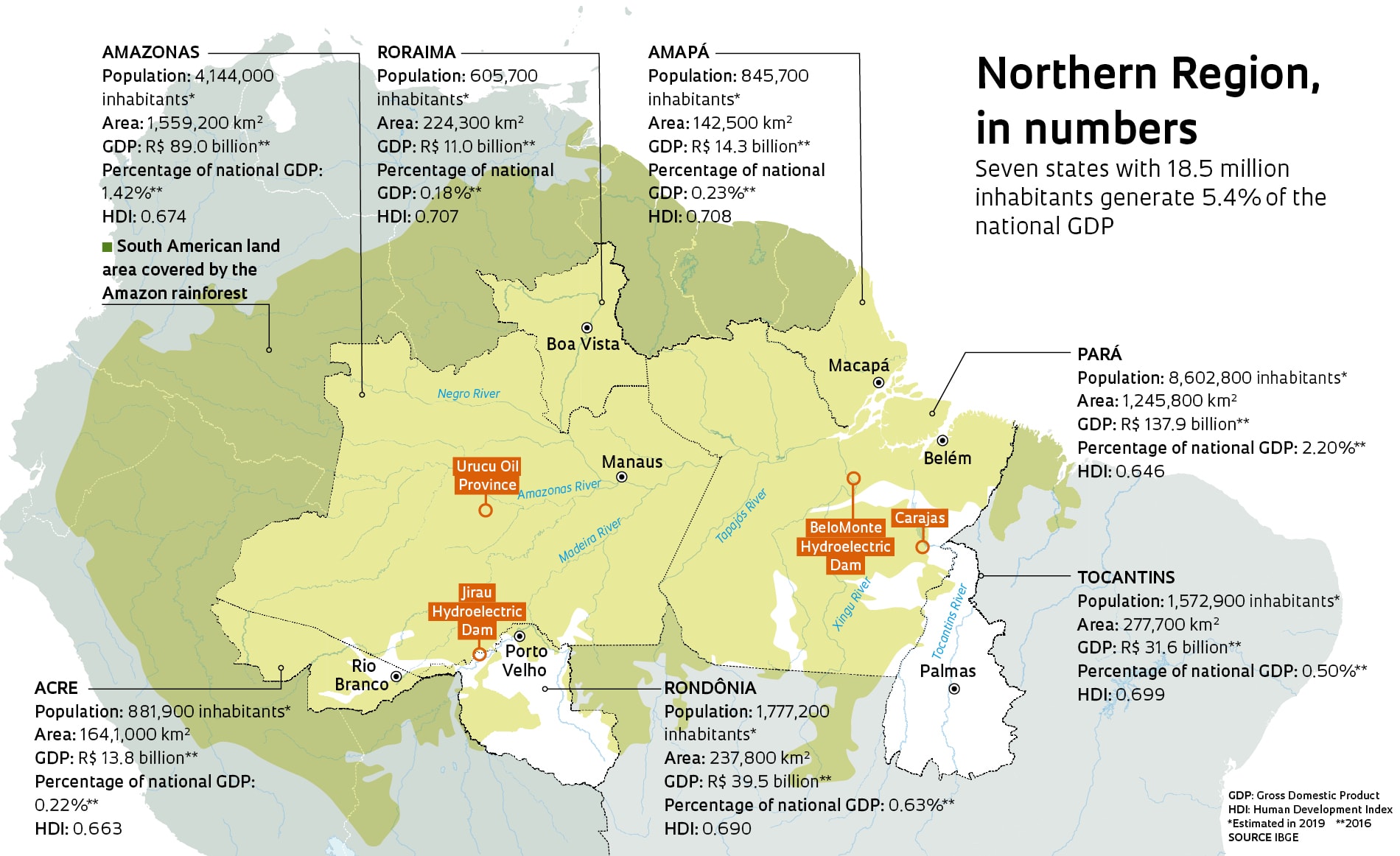

Despite this wealth, the Amazon currently has close to 28 million inhabitants and is marked by deprivation. Although the region accounts for 20% of the river and lake water on the planet, it also has the country’s lowest levels of access to treated water and sewage collection. Of the 18.5 million inhabitants of the northern states (Acre, Rondônia, Roraima, Amazonas, Pará, Tocantins and Amapá), only 70% live in houses with potable water and only 13% have sewage collection, according to data released this year by the National Sanitation Information System. The region’s school performance indices and per capita income are also among the lowest in Brazil. “The northern region remains the poorest in the country,” confirms economist Maria Amélia Enríquez, a professor at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA). “Since the 1940s, people’s income levels have not improved compared to other Brazilian regions,” she observes. “The marginal living conditions haven’t changed.”

– The rainforest

– Two Amazons

– Paulo Moutinho: Standing in the forest

– Lauro Barata: The network of natural wealth

Bertha Becker (1930–2013), a Brazilian geographer who focused on the tensions and strategies related to the occupation of the Amazon, said that the region, like Brazil and other Latin American countries, was the oldest periphery of the global capitalist system. The arrival of European colonization in the sixteenth century saw the beginning of a type of occupation and development known as a frontier economy. It was based on the continuous annexation of land and exploitation of natural resources, both seen as being infinite.

Rogerio Assis

Extensive livestock farming is one way of advancing on the public forestlands in the AmazonRogerio AssisThe means by which the metropolis acted on marginalized peripheries was incorporated into national policy. It was used by the government in the last century to integrate the Amazon with the rest of Brazil, and is still in practice. On the southern and southeastern borders of the Amazon, in a band that runs through the states of Rondônia and Mato Grosso, to the west, and Pará and Maranhão, to the east, illegal occupation and deforestation of public lands occurs first, paving the way for cattle ranching, which subsequently gives way to soy farming. It is in this region, known as the Arch of Deforestation or, as Becker preferred to call it, the consolidated settlement arch, that many of the Amazon’s small and medium-sized cities are located. Large-scale mining and high-tech farming—which is theoretically more efficient and economically profitable, but employs fewer people—are centered there, as well as illegal mining and logging operations.

In the 1990s, the realization that natural resources are scarce and finite helped bring about a reassessment of nature, which followed two rationales. In a 2005 article in the journal Estudos Avançados, Becker called the first rationale “civilizing,” concerned with nature and the intrinsic value of life, which is the origin of the environmental movement. The second rationale follows the logic of accumulation, which sees nature as a “reserve of resources for the realization of future capital.” Over the past 30 years, the positive reassessment of the value of nature has strengthened the work and organization of family farms, environmental groups, indigenous forest peoples, and scientists. These groups have been opposing the expansion of agribusiness—which consumes natural resources—for some time, creating tensions and, according to current federal government talking points, impeding the region’s economic growth.

Despite what has been claimed, the stagnation is not real. From 1960 to 2015, the region’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew at an average rate of 5.9% per year, above the national average of 4.1%. The North region’s GDP reached R$337.2 billion in 2016, according to the latest data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE). This corresponds to 5.4% of the national economy. When data is included from Mato Grosso and the greater part of Maranhão, the other two states that make up the Legal Amazon, the figure rises to R$537.2 billion (8.6% of Brazil’s GDP). “The economy of the northern region is not in decline or in a state of low growth,” says economist Aristides Monteiro Neto of the Institute for Applied Economic Research (IPEA). “Although the region’s GDP is modest, its growth has been high by any standard.”

Rogerio Assis

Soybean cultivation is one way of advancing on the public forestlands in the AmazonRogerio AssisProgress in recent decades, however, has come partly at the expense of the rainforest. From 1985 to 2018, the Amazon lost 47 million hectares of native vegetation. Of this total, 39 million hectares were turned into pasture and 6 million into plantations, according to data presented in August this year by MapBiomas, a collaborative project between universities, technology companies, and NGOs that maps changes in land cover and land use in Brazil. It’s as if the vegetation of half of Mato Grosso, the country’s third-largest state, had been eliminated and replaced by pasture grass, soybeans, corn, and cotton.

Faced with this scenario, a question arises. Is it possible to make the Amazon economy grow in a way that is fair and sustainable, and preserves the forest? The answer is neither singular nor simple, and some of the possible solutions still need to be tested.

“We can’t make the mistake of thinking that the Amazon’s problems are going to be solved with a silver bullet,” says ecologist Paulo Moutinho of the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), an NGO that works to integrate scientific research with the social needs of the Amazonian region. He attended the October meeting of the Ciência Aberta (Open Science) debate program, organized by FAPESP and the Folha de São Paulo newspaper, where he stated that it is possible to make sustainable use of the forest, even with timber harvesting, when linked to a more technological type of agriculture and more intensive livestock farming. “We tested this in a small area of Pará and within four years we were able to increase income by 120% and reduce deforestation by 78%. It is possible to combine opportunities,” Moutinho said.

Rogerio Assis

Collecting Brazil nutsRogerio AssisWhatever solutions are adopted, they will not be able to disregard what has already been done and will have to deal with the particularities of each state. The model of occupation that has prevailed in the Amazon created a regional economy that is important to the national economy, even though it’s connected with deforestation and the concentration of wealth and land in the hands of only a few.

The Amazon is now the second-largest soybean-producing region in Brazil, which is the second-largest producer of soybeans globally. Of the 114.8 million tons harvested across the country in the 2018–2019 crop, 32.5 million (28%) came from Mato Grosso. The region also accounts for 36.4% of Brazil’s cattle population, which is the second largest in the world. There are almost 80 million head of cattle on Amazonian lands—30 million of them in Mato Grosso, and 20 million in Pará.

“The first challenge is to render the production of these two commodities—which are fundamental to the Brazilian economy—non-predatory. The world is asking this of Brazil,” says sociologist Ricardo Abramovay of the University of São Paulo (USP). “Increasingly, the capacity for Brazilian products to compete will depend on the availability of information on how they are produced.”

Rogerio Assis

Latex extraction from a rubber tree in the rainforestRogerio AssisAn alternative source of animal protein and income generation in the Amazon may be in fish farming, with the domestication of species with high commercial value, such as pirarucu. Another proposal to boost the region’s economy, while preserving the forest, is to make livestock farming more intensive (raise more animals per hectare) and convert abandoned pasture into agricultural land. It is estimated that 20% of the Amazon rainforest has already been cleared, about 80 million hectares. Most of that land (53 million hectares) is currently occupied by livestock farming, which varies from low to high productivity. “For almost two decades there has been a shift from cattle to agricultural activity in the southern Amazon states,” says agronomist Alfredo Homma, a researcher at the Eastern Amazon division of the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA). “Cattle farmers are beginning to realize that it’s no longer worth it to raise one head per hectare.”

Besides recommending more intensive cattle farming, Homma supports using degraded pastures for domesticated cultivation of native species that have commercial value. It’s a long list. There are trees, such as cocoa, acai, rubber, Brazil nuts, bacuri, rosewood, and copaiba, among others species. “There is a movement to use native plant products for cosmetics, food, pharmaceuticals, and plastics,” says chemist Lauro Barata of the Federal University of Western Pará.

Indigenous peoples, small-scale extractivists, and riverine dwellers have long been collecting fruits and other products from these plants and marketing them in cities. It is the simplest form of extractivism, sometimes modified by managing and more densely planting forest crops. Many see in it a means of harmoniously coexisting with nature. Homma sees a loss of opportunity and a population condemned to poverty. “Extractivism is a way to buy time until a plant is domesticated, which depends on a lot of research,” he says. “Extractive production, however, cannot meet market demand when the demand increases.”

Rogerio Assis

The acai street market in BelémRogerio AssisThere are other research groups that think differently. Economists from the UFPA Center for Advanced Amazon Studies (NAEA) have been investigating the acai economy for more than a decade, including its relationship with the dynamics of fruit production in managed forest areas at the mouth of the Amazon River, and have determined acai is an important source of jobs and income.

Pará is the national leader in the production of this fruit; harvesting almost one million tons per year. Acai production drives a value chain that is not easily measured using traditional economic metrics, and has consequently been largely invisible. To understand this market, NAEA economist Francisco da Costa Assis had to develop appropriate metrics to assess the contribution of each actor in this production chain. Extracting information from the 1996 and 2006 agricultural censuses, Costa and economist Danilo Fernandes measured the evolution of the production chains of acai and other products of agro-extractive origin, and their part in the region’s agricultural economy. In 2006, family-based extractive production was responsible for 21% of the northern region’s R$26 billion rural economy, and 26% of rural employment. This almost matched the cattle industry, which accounts for 25% of the northern economy and 10% of rural land occupation, according to an article published in 2016 in the Revista de Economia Contemporânea (Journal of Contemporary Economics).

“The Amazonian agricultural economy has been expanding on the basis of soybean and cattle monocultures. To produce more, they need deforested areas, which stimulates illegal occupation and growth in the land market,” explains Fernandes. According to the researcher, the production of acai berry and other fruits based on agro-extractivism and collective land use has always been viewed as primitive and associated with poverty. “Only now are we able to show the value of this production chain, which through proper management can increase productivity without clearing the forest,” he says.

In a recent survey, Raoni Rajão and colleagues at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG) estimated that the production from one hectare of managed acai yields a gross income of R$26,800, ten times higher than that of soybeans. “Acai, collected by traditional communities in small areas, can generate a good income and more jobs than soy, which is highly mechanized,” says Rajão. Earnings may increase if value is added to the product. “This information may help increase appreciation for forest products and reduce the temptation for small-scale producers to sell their land.”

Acai is perhaps the most concrete case of income generation that preserves the forest. However, it isn’t the only one. Natura, one of the largest cosmetics companies in the world, has been using Amazonian raw materials in its products for 20 years. They use oils and extracts collected by 5,300 families that have adopted agroforestry management, and contribute to the conservation of 257,000 hectares of rainforest. The company also invests in improving sustainable production chains, and in studies to identify active plant compounds and expand the use of biodiversity.

Despite these examples of success, it will still be necessary to verify the economic potential of many Amazonian products. Proof of such potential is, in fact, a requirement to convince rural producers and other economic agents, as well as government managers, that it may be more profitable to sustainably extract what nature offers than to knock it down to make room for crops and animals that deplete the land’s productive capacity. “One difficulty is that the size of the rewards that might be generated by new products from the bioeconomy, such as pharmaceuticals and cosmetics, is not yet known,” says Abramovay. “However, if government policies favor only the strategies that wipe out the forest, we’ll never know if the other path could work.” Monteiro, from IPEA, believes the Amazon is multifaceted and needs different development strategies. “These strategies,” he says, “have to proceed on the basis of knowledge that will modify the pattern of socioeconomic occupation.”

Danilo Verpa / Folhapress

Iron extraction mine in Canaã dos CarajásDanilo Verpa / FolhapressThe economies and social structures of the region’s states are as diverse as the forest that covers the Amazon. “The Amazon is a huge region, with states that have very disparate production structures,” says economist Rodrigo Portugal, from the Institute of Applied Economic Research (IPEA). A brief analysis of data on the two largest states in the region, Amazonas and Pará, reveals a few of these differences.

Amazonas, the largest Brazilian state, has the largest area of preserved forest, and a highly urbanized population dependent on industrial activity. Of the 4.14 million Amazonas residents, 82% live in cities, with the majority of these (2.2 million) living in the state’s capital, Manaus. The state’s GDP was R$89 million in 2016, equivalent to 26.4% of the North region’s economy and 16.6% of the economy of the Legal Amazon, making Amazonas the state with the second largest economy in the North and the fourth largest in the Legal Amazon. It is estimated that just over one-third (35%) of its GDP was generated by the industrial sector.

Of the nearly 1,200 companies in Amazonas, 496 are located in the industrial zone of Manaus, its Free Trade Zone, which was created in 1967 with the aim of becoming a development hub in the Western Amazon. These companies manufacture electronics, chemicals, motorcycles, steel, and other metal products, among others, and generate 87,000 direct jobs. They provide jobs to a significant portion of the Manaus population.

Lalo De Almeida / Folhapress

A motorcycle assembly line in the Manaus Free Trade Zone, in AmazonasLalo De Almeida / Folhapress“There is a sophisticated and diverse industrial park there, which locally produces a portion of the components used in its products, and conducts research. Many of these companies could be located in any country in the world,” says economist Márcio Holland de Brito of the São Paulo School of Economics of the Getulio Vargas Foundation (EESP-FGV). Just over a year ago Holland was commissioned by the Amazonian industrial sector to coordinate an analysis of the costs and benefits generated by the Manaus industrial zone. The results of the study, titled “Zona Franca de Manaus: Impactos, efetividade e oportunidades” (The Manaus free trade zone: Impacts, effectiveness and opportunities), is available on the internet at (bit.ly/2MEjd9W).

The economist and his team concluded that the Free Trade Zone had a major impact on earnings in Amazonas. Since its implementation in the late 1960s, annual per capita income in the state has grown faster than in other industrialized regions of the country. In 1970, per capita income in São Paulo was R$17,400 (adjusted values). In Amazonas, average earnings were only 14% of those in São Paulo, about R$2,400 per year. By 2018, Amazonas income was up to R$17,000, or around 55% of the annual average in Sao Paulo (R$30,000). During this period, the population of Manaus grew by a factor of twelve and the state grew six-fold, while the Brazilian population as a whole tripled in size.

These results are due to a consistent, ongoing policy of encouraging regional development. Companies in the Free Trade Zone benefit from a federal incentive in the form of a tax waiver that has been in force for half a century, and which was recently renewed until 2073. A decade ago this incentive represented about 11% of annual federal tax spending. In 2017, it was at 8.5%, or about R$25.6 billion. Critics of the program say it is expensive, but according to Holland, it’s difficult to calculate the cost. In 2017, the federal government collected R$14 billion in taxes in Amazonas; the state government another R$16 billion; and the municipality of Manaus, R$4 billion. “I can’t imagine Manaus and Amazonas collecting taxes without the existence of the industrial zone,” he says.

Although well established, the Manaus Free Trade Zone is at risk of falling apart. Industries in the region face serious logistical problems distributing their products to the greater domestic market and may lose their competitive edge, depending on how tax reform currently being discussed is implemented. In addition to the socioeconomic consequences, a possible disruption of the Free Trade Zone could affect deforestation. There are indications that by employing approximately 12% of the state’s population, its existence may contribute to reducing deforestation. The challenge, according to FGV researchers, is to find a sustained and sustainable way to continue growing, without deforestation, and with less reliance on federal government resources.

The state of Pará, with an estimated population of 8.6 million, has the highest GDP in the Amazon (R$138 billion in 2016), and at the same time one of the region’s highest percentage of poor people. The average income in the state (R$803 per month) is 40% below the national average, with four out of ten state residents living below the poverty line. The state is the second-largest producer and exporter of ores in the country. In 2018, 220 million tons were extracted, generating US$16 billion. This value exceeds the GDP of many countries and is important in maintaining Brazil’s trade balance. It accounts for almost a third of Pará’s GDP, but because of tax exemptions, only a small portion of this money goes to the state government. “Without compensation from taxation on its primary commercial activity, it’s difficult for Pará to make the investments in physical and social infrastructure necessary to overcome its marginalized conditions,” says economist Maria Amélia Enríquez, a researcher at UFPA.

As a result, the biggest beneficiaries of mining are the corporate shareholders—who receive profits and dividends—and the federal government, which uses export currencies to ensure the surplus needed to balance the country’s foreign accounts.

“Although home to one of the principal Brazilian mineral-ore regions, Pará is one of the states with the lowest revenues,” says the economist, formerly the state’s Secretary of Industry, Trade, And Mining (2014) and Assistant Secretary of Science and Technology (2016–2018). Formulated in 2012, the Pará State Mining Plan (2014–2030) has projected production will continue growing in the state, doubling exports over the next 20 years. In Enríquez’s opinion, an improvement in the state’s investment capacity will depend on a change in federal law.

Scientific articles

BECKER, B. K. Geopolítica da Amazônia. Estudos Avançados. Vol. 19, no. 53, pp. 71–86. 2005

COSTA, F. A. and FERNANDES, D. A. Dinâmica agrária, instituições e governança territorial para o desenvolvimento sustentável da Amazônia. Revista de Economia Contemporânea. Vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 517–552. 2016.