Digital Library of Historical Cartography at USPDetail from the map Praefecturae de Paraiba et Rio Grande, created by the German naturalist Georg Marcgraf (1610–1644) circa 1640, which shows a troop of indigenous people commanded by a Dutch military officerDigital Library of Historical Cartography at USP

When the 1988 Brazilian Constitution formally recognized indigenous peoples’ rights to the lands they inhabit, it engendered new legal procedures for territorial demarcation and delimitation that continue to this day. Throughout every region of Brazil, these claims generated a profusion of studies, technical reports, and legal opinions, produced by the technical groups that conducted the ethnohistorical, anthropological, environmental, and cartographic studies the new legislation required. In each of these initiatives, there is one common element: the maps.

The anthropologists, cartographers, environmental managers, and historians working in the technical groups turn to myriad forms of maps to conduct their research. There are official depictions, made during the colonial period, under both the Empire and the Republic. There are hand-drawn representations made by early inhabitants and images produced with the help of modern satellite navigation systems, such as GPS and phone apps. Other depictions are transposed from oral accounts or recovered from ancient descriptions. Anthropologist Estêvão Palitot, from the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB), has been working with landholding regularization for two decades, accumulating a collection of maps that encompasses the diverse types of mapping needed for indigenous peoples to recover their lands and identities.

Gathering together these maps and other documents, Palitot and fellow anthropologist Lara Erendira Almeida de Andrade, who holds a doctorate from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), created the website Atlas do Pernambuco Indígena. Andrade, now a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institute of Scientific Research in Canada, says that thanks to her experience as a cultural producer in Recife, she saw in the material an opportunity to make the documentation available to the public. “We decided to use nonspecialized language and short texts accompanying each map, with a search tool so that visitors can navigate the collection,” she says. The first set of documents, with 23 accompanying text entries, has been online since January.

The Atlas presents the variety of cartographic processes expressing the relationship of a human group to a territory, what the geographer Milton Santos (1926–2001) called “territoriality.” It deals with the lived territory, or “the ways in which the land gains meaning, based on its symbology, its use, and its representation,” says geographer Maurice Seiji Tomioka Nilsson, who has been mapping indigenous lands since the 1980s, and today works as a consultant for the nongovernmental organization Centro de Trabalho Indigenista (CTI), based in São Paulo.

Andrade notes that cartography has been gaining increasing importance in the field of anthropology in contexts such as indigenous teacher training, the demarcation and environmental management of indigenous lands, and producing technical reports for landholder regularization. “The indigenous peoples themselves have a need to utilize georeferencing tools to strengthen their struggle for territorial rights,” he says.

Historical cartography has been fundamental in demarcation projects, especially for analyzing maps produced during the late eighteenth century, after the signing of the Treaty of Madrid in 1750, which established the territorial boundaries between the Portuguese and Spanish colonies in South America, according to historian Íris Kantor, coordinator of the Historical Cartography Studies Laboratory of the Jaime Cortesão Chair (LECH) at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo. “During this period, maps were drafted by military and scientific expeditions with the goal of urbanizing the indigenous people, in addition to facilitating fortress building and tax collection, and establishing land and river communication routes.” Today, “the availability of high-resolution digital cartography and the cataloging of cartographic specimens make it possible to use these two-dimensional geographic information systems for ‘counter-colonial’ purposes,” he says.

Digital Library of Historical Cartography at USPThe map Praefecturae Paranambucae pars Meridionalis, also by Marcgraf, uses conventional symbols to represent towns, villages, indigenous villages, fortresses, and mills. The right side depicts a scene believed to be most likely from the Quilombo de PalmaresDigital Library of Historical Cartography at USP

The use of historical maps requires a variety of expertise, the researcher explains. They are classified according to criteria such as backing medium, graphic language, and target audience. “It’s fundamental to examine the social processes involved in their production, circulation, and appropriation,” he says. In preparing technical reports, the presence or absence of toponyms (place names) on maps makes it possible to reconstruct the successive forms of occupation within a geographic area. “This transposition cannot be immediate or inadvertent, because the names of places vary from cartographer to cartographer. The studies must take into account the relationships with other maps of the region,” he points out. This method of analysis also requires knowledge of the history of indigenous languages and how they have interacted with the languages of colonizers.

Palitot points out that the oldest records of indigenous occupation made by Europeans are in northeastern Brazil. “But these areas aren’t fully demarcated; they are the subjects of much conflict and litigation. Anthropologists working in the Northeast have to deal with history and cartography a lot, because we constantly have to go back to maps and reconstruct what’s been done with the territories over the centuries,” he explains.

There are two crucial moments in the history of indigenous occupation in the Northeast: the mission settlements, which took place in the colonial period, and the land donations made during the Empire. The village settlements were created by Jesuit missionaries, with the aim of catechizing the local population. The Imperial donations also had the goal of integrating these peoples into the Western way of life, moving them away from their own traditions and beliefs. Churches built on the donated land became the center of normal life. There was an expectation that the native population would become Christian and that their indigenous roots would be lost in the mists of time. “About 100 small towns in the region have their origins in these early villages. Most of our work consists of discovering—in historical documents—what happened in these places,” says the UFPB anthropologist.

The researchers have found alternating periods of intensive documentation and gaps in time with no information. In her studies on the Macaco Settlement of the Kapinawá people in the Serra do Catimbau, in Pernambuco, Andrade reports finding an abundance of documents from the colonial period, followed by 100 years of “cartographic emptiness.” “And suddenly, at the end of the twentieth century, the Kapinawá reappear there. Why? Understanding this ‘suddenly’ requires rigorous historical study,” observes the anthropologist.

Something similar occurs in the succession of censuses, argues Palitot, and helps to explain the sudden reappearance of indigenous people in certain territories. Every census count of the country’s population involves the decision of how to account for the social groups that inhabit each area. If an administration considers that the indigenous peoples of a particular area have been assimilated into the rest of the population, they may be disregarded.

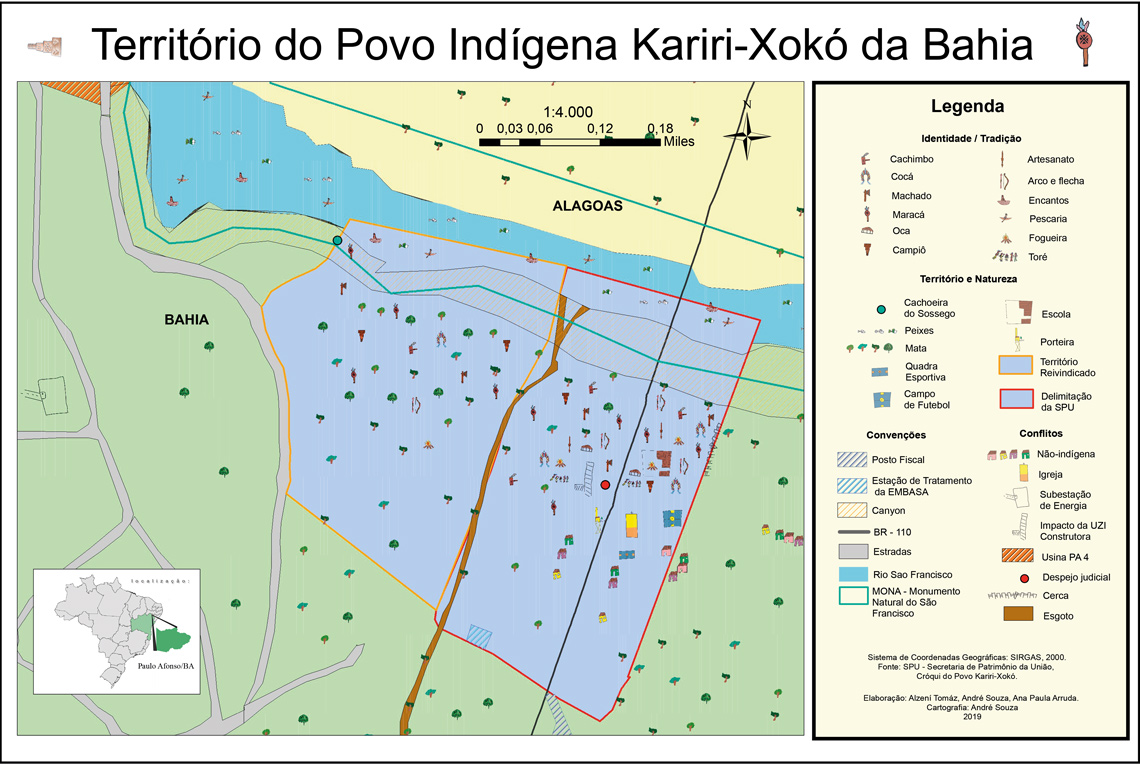

Projeto Nova Cartografia Social da AmazôniaA map prepared from a sketch by the Kariri-Xokó people indicates cultivated areas and housing, but also shows conflicts with nonindigenous peopleProjeto Nova Cartografia Social da Amazônia

In the first two Brazilian censuses, in 1872 and 1890, the indigenous people appear as “caboclos” (mestizos), without distinction of ethnicity or linguistic group, expressing the era’s aspiration toward a homogeneous and mixed-race population. Throughout the twentieth century, there was a large variation in criteria, with some censuses lacking even the item “color and race.” Since 1991, as a result of the new Constitution, the indigenous population began to be accounted for in more detail, including their languages. That year, 294,131 individuals were recorded, a number that grew to 734,172 in 2000 and 817,963 in 2010.

Palitot associates the rapid increase, in part, with “the process of valuing indigenous identities,” and partly with the implementation of public policies that had a specific focus on these peoples, especially regarding education and health, which helped promote the recovery of ethnic identities. The increase in registrations of indigenous populations also stems from the fact that, from 1991 to 2000, the census began to visit communities further away from the urban centers of the Amazon region.

The anthropologist says the count shows that these peoples have always been in those places and have never ceased to be indigenous. Despite centuries of settlements and expulsions, their identities have never completely disappeared, manifesting themselves in customs preserved behind their adoption of Western habits. “Various elements show the indigenous peoples’ significant sense of proud self-determination. In the Northeast, there are myths in which the image of a saint was moved, but returned to its place by itself: the land was hers and she wanted to stay with her children, the indigenes,” he says.

The constitutional mechanism that gave this process momentum was Article 231, the first paragraph of the Brazilian Magna Carta, which recognizes these distinct territorialities, says Nilsson. Indigenous lands are defined as “those permanently inhabited; those used for their productive activities; those essential to the preservation of the environmental resources necessary for their well-being; and those necessary for their physical reproduction and maintaining their culture, according to their uses, customs, and traditions.”

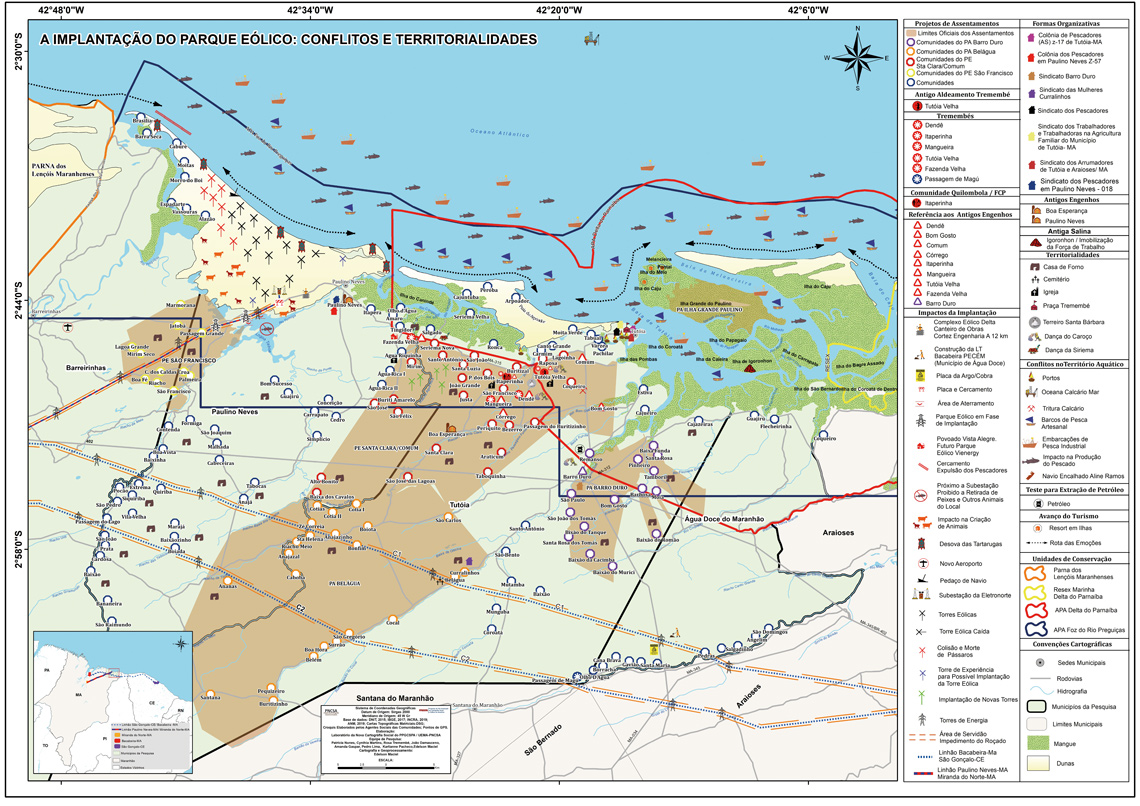

Projeto Nova Cartografia Social da AmazôniaThe impacts of implementing a wind power project on communities of fisherpeople on the coast of MaranhãoProjeto Nova Cartografia Social da Amazônia

A geographical consultant for the CTI, Nilsson believes this is “a major legal transformation, because it links the land not to a person, but to a people,” establishing a bridge between the national landholder system and traditional territorialities. Based on this definition, populations that had been hesitant to recognize themselves as indigenous began to reclaim their native status in an effort to reestablish their territories. The prior hesitation had been the result of official pressure towards acculturation, in addition to the recurring fear of violence.

Beyond researching the historical documents, new maps must be produced that can represent geographical features key to the group’s life, such as sacred mountains or rivers used for fishing. In other words, territoriality. The initiative in which a population participates directly in the mapping of their land is given different names, such as “participatory mapping,” “mental mapping,” or “ethnomapping.”

Participatory mapping has been an important part of the environmental management of indigenous lands, which became public policy in 2012 with the implementation of the National Policy for Territorial and Environmental Management of Indigenous Lands (PNGATI). “This is an initiative that was being done first, to be thought about later. During advisory meetings with indigenous peoples—regarding both territorial and educational policy—they always expressed their social and environmental concerns because there was someone trying to invade and devastate their lands,” recalls Nilsson, who participated in several demarcation processes and various studies within the scope of PNGATI. Putting a territory on paper was the best method found for protecting it.

Participatory mapping involves gathering testimonials from indigenous people, particularly elders, who describe the problems their people are facing, and the key geographical features of the area being reclaimed. Then the mental maps are drafted, during which the territory can be drawn freehand. On some occasions, this process also includes conducting cartography workshops. Next comes fieldwork, wherein the territory’s most significant areas are visited and registered using GPS. The collected data is superimposed on satellite images.

The mapping tools used by the communities involved are at the core of the project “Nova cartografia social da Amazônia” (New social cartography of the Amazon), an ongoing initiative since 2005 designed by anthropologist Alfredo Wagner Berno de Almeida, from the State University of Amazonas (UEA).

Almeida’s social cartography had its origins in his mapping work for the Grande Carajás project during the 1980s, a massive program aimed at mining and industrializing the Pará region by implementing an extensive railroad, and installing steel mills in the area of Marabá, Pará. Almeida’s experience is related in his book Carajás: A Guerra dos mapas (The war of the maps) (Farangola, 1993).

“To make a map of economic projects like this, all the necessary information can be found at institutions such as the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics [IBGE] or the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources [IBAMA],” observes anthropologist Emmanuel de Almeida Farias Júnior, from the State University of Maranhão (UEMA), one of the project’s researchers. All the distinct areas, transmission lines, roads and railways, rivers, and cities are there, he points out. But that doesn’t tell the whole story. “This information has the typical limitations of a document made for official purposes,” he says. “Social cartography emerged out of the realization that the social impacts of an initiative of this size don’t appear on a map if they’re not defined by the people who live in that place. And what goes into that map? Anything these people indicate is relevant and meaningful.”

Farias Júnior uses the region of the Tapajós River, in Pará, as an example. The maps used in the environmental impact reports for the hydroelectric complex planned for the region represent the river using a blue line, in accordance with traditional cartographic convention. “With social cartography, the indigenous people were able to map the ‘river wells,’ deeper sections of the river, where certain fish can be caught that are absent from the shallow sections. There are many more layers of meaning than what appear on official maps. Thus, those making decisions about environmental or social impacts, such as the Public Prosecutor’s Office or the Public Defender’s Office, have a clearer view of what is happening there,” he says.

For Farias Júnior, the “New social cartography of the Amazon” project works as a link between researchers and social movements. Almeida named his technique “social cartography” to emphasize this connection, which must remain continuous, which is not necessarily the case with participatory mapping in general. The workshops and other stages of the process are conducted at the request of groups involved in a conflict, be it territorial, linguistic, or cultural. Social cartography can also be applied to the urban environment. Farias Júnior cites as examples the LGBT+ communities in Manaus, Amazonas and Belém, Pará, and the recycling pickers of Manaus. These groups indicated to the researchers the need for registering on maps the places in their cities that are important to them.

In social cartography and other forms of participatory mapping, the process of combining the two techniques—mental mapping and satellite imagery—creates a delicate situation. There is a risk that the technological data will overwhelm the information brought in by the community, due to the often immediate availability of the images and their high degree of detail. “The foundation of a good transposition of information is effective knowledge of the territory, which is obtained during the previous stages,” Nilsson explains. “In truth, the information that comes from the reports is richer and more relevant. So, we have to think about methods to obtain symmetry between the two techniques, which aren’t naturally harmonious,” he adds.

Kantor points to a similar difficulty in the field of historical cartography. “Combining different practices of spatial representation in the same database is a crucial issue. Superimposing these layers of information has to be done methodically, so that it becomes possible to make comparisons and cross-references,” he observes. To do its job most effectively, the image repository “must have collaboration from ethnographers, archaeologists, botanists, geologists, historians of cartography, linguists, and specialists in information technology and artificial intelligence, among others.”

Scientific articles

ANDRADE, L. E. A. Povos indígenas, mapeamentos participativos e política de gestão territorial: O caso do Semiárido brasileiro. Vivência: Revista de Antropologia. Vol. 1, no. 52. 2019.

ASSIS, W. F. T. Pode o subalterno mapear e incidir no planejamento regional? Conflitos territoriais e disputas cartográficas no ordenamento fundiário do oeste do Pará. Revista Brasileira de Estudos Urbanos e Regionais. Vol. 22. 2020.

NILSSON, M. S. T & VIANA, D. Política e tecnicidade dos mapas: Sobre o mapeamento participativo em três terras indígenas da bacia do rio São Francisco. Anais da VIII Reunião de Antropologia da Ciência e da Tecnologia. 2022.

PALITOT, E. M. Marcos, rumos, posses e braças quadradas: Refazendo os caminhos da demarcação da Sesmaria dos índios de Monte-Mór – Província da Parahyba do Norte (1866–67). Outros Tempos, Vol. 19, no. 34. 2022.

PEREIRA, C. E. G. et al.Trajetórias da cartografia: Da colonialidade à descolonialidade. Revista de Geografia. Vol. 39, no. 1. 2022.

Book

ALMEIDA, A. W. B et al. (orgs.). Mineração e garimpo em terras tradicionalmente ocupadas: Conflitos sociais e mobilizações étnicas. Manaus: UEA Edições; PNCSA, 2019.