On February 19, 1619, a young Portuguese man named Antônio Raposo Tavares (1598–1659) stepped into the Jesuit College in Salvador, Bahia, to lodge a denunciation with the Inquisition. He accused New Christian Manoel Soares—a Jew converted to Catholicism—of fleeing Portugal to Brazil after aiding another convert, a woman, in escaping the Tribunal of the Holy Office. Years later, Raposo Tavares would migrate to southeastern Brazil and gain notoriety for enslaving Indigenous people to labor on sugar plantations, becoming one of the most prominent bandeirantes—frontier settlers who played a central role in expanding Portuguese colonial rule.

This addendum to Tavares’s biography came to light thanks to the discovery of long-lost documents from the Inquisition’s second visitation to Brazil, unearthed by historians Angelo Adriano Faria de Assis and Ronaldo Vainfas, professors at the Federal University of Viçosa (UFV) and Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ). Their findings were published in the book, Segunda visitação da Inquisição à Bahia (Second visitation of the Inquisition to Bahia [1618–1620]), published by Cosac.

In 2021, the pair traveled to Lisbon’s National Archive of Torre do Tombo while preparing a new edition of the book Denunciações da segunda visitação do Santo Ofício à Bahia – Século XVII, (Denunciations from the second visitation of the Holy Office to Bahia – Seventeenth century), originally compiled by historian Rodolpho Garcia (1873–1949). First published in 1927, Garcia’s book documented 52 cases recorded by inquisitors during that second mission. Assis and Vainfas, however, uncovered an archival dossier containing 239 denunciations—nearly quintuple the number previously known.

“We found the complete file, including names of both accusers and accused that had never surfaced before,” Vainfas explains. The researchers determined that the 52 cases published in 1927—and later expanded to 84 in the volume Denunciações da Bahia: Denúncias feitas ao Santo Ofício em Salvador em 1618 (Denunciations in Bahia: Reports to the Holy Office in Salvador in 1618), compiled by independent historian Antônio Fontoura and self-published in 2020—were drawn from just two record books from that visitation. “Inquisitors typically sent records to Lisbon in batches, spread across multiple ships, since they feared shipwrecks and pirate attacks. That’s why so many dossiers survive only in fragments,” Vainfas explains.

Beyond the complete file, the new book also features essays by Assis and Vainfas that describe the period, explain the procedures of the Inquisition, and analyze how the Holy Office shaped life in colonial Bahia. “Up until now, the second visitation was regarded as a minor episode because of the limited number of cases,” notes Assis. “But the testimonies uncover striking details—marital intimacies, same-sex relationships, and the practice of syncretic religions that blended Catholicism with Indigenous mythologies and African deities.”

Death at the stake

The Inquisition was founded in the thirteenth century by Pope Gregory IX to try and punish those who deviated from Catholic doctrine. It reached Portugal in 1536, where its main targets were New Christians suspected of secretly practicing Judaism. Inquisitors conducted interrogations that often involved physical torture, gathering denunciations, confessions, and witness statements. These could culminate in full trials and even capital sentences, most commonly execution by burning at the stake.

Within the Portuguese Empire, permanent Holy Office tribunals were established in Lisbon, Coimbra, and Évora in Portugal, and in Goa, India—then a Portuguese colony. In Brazil, by contrast, the Inquisition functioned through sporadic visitations and a network of local deputies over the course of its 285-year presence. Altogether, roughly 45,000 people across Portuguese territories were prosecuted.

Many in Brazil applied to serve as Inquisition bailiffs, known as familiares

According to historian Alécio Nunes Fernandes of the University of Brasília (UnB), there were four inquisitorial visitations to Brazil. The first took place between 1591 and 1595 in Bahia, Pernambuco, Itamaracá, and Paraíba. The second, between 1618 and 1620, was followed by another mission in 1627–1628 to the southern captaincies, primarily São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro. Little is known about that third visitation, however, since its records are thought to have been lost in a shipwreck. The fourth and final visitation occurred between 1763 and 1769 in the former state of Grão-Pará, in northern Brazil.

The Inquisition relied on the Catholic Church’s deep roots in Brazil, notes historian Aldair Rodrigues of the University of Campinas (UNICAMP). “The Church had a far greater presence across the territory than the Crown itself. When the monarchy needed to announce something—say, a new tax edict—it used parishes and dioceses to spread the word,” he explains. “The Inquisition tapped into that ecclesiastical infrastructure to extend its reach.”

Rodrigues adds that the Inquisition found eager support within Brazil’s colonial society. “Many people applied to serve as Inquisition bailiffs, known as familiares,” he says. “Applicants had to undergo a costly vetting process to prove their ‘purity of blood’—that they were Old Christians [Catholics by birth] with no relatives previously condemned by the Inquisition. Once approved, they were sworn into the service of the Holy Office.”

For these familiares, their alignment with the Inquisition brought prestige. “They enjoyed privileges such as immunity from local courts, along with special clothing and insignia,” Rodrigues notes. “This obsession with blood purity and intolerance became embedded in the making of Brazil’s elite, where power increasingly concentrated in the hands of white Old Christians.”

In 2023, Rodrigues and historian Moacir Maia of UFV published the book Sacerdotisas voduns e rainhas do Rosário: Mulheres africanas e Inquisição em Minas Gerais (século XVIII) (Vodum priestesses and Queens of the Rosary: African women and the Inquisition in Minas Gerais [eighteenth century]), with publisher Chão Editora. The book is a collection of documents the two uncovered in Lisbon’s National Archive of Torre do Tombo and in local archives across Minas Gerais.

“Most of these women came from Benin, part of the African region the Portuguese called Costa da Mina, and practiced the vodum religion. In Brazil, they gained prominence as merchants,” Rodrigues explains. “They sought upward mobility and were often crowned Queens of the Rosary, in honor of the Virgin Mary. Yet even as they embraced that Catholic facet, they preserved their African rituals—a duality that made them targets of the Inquisition.”

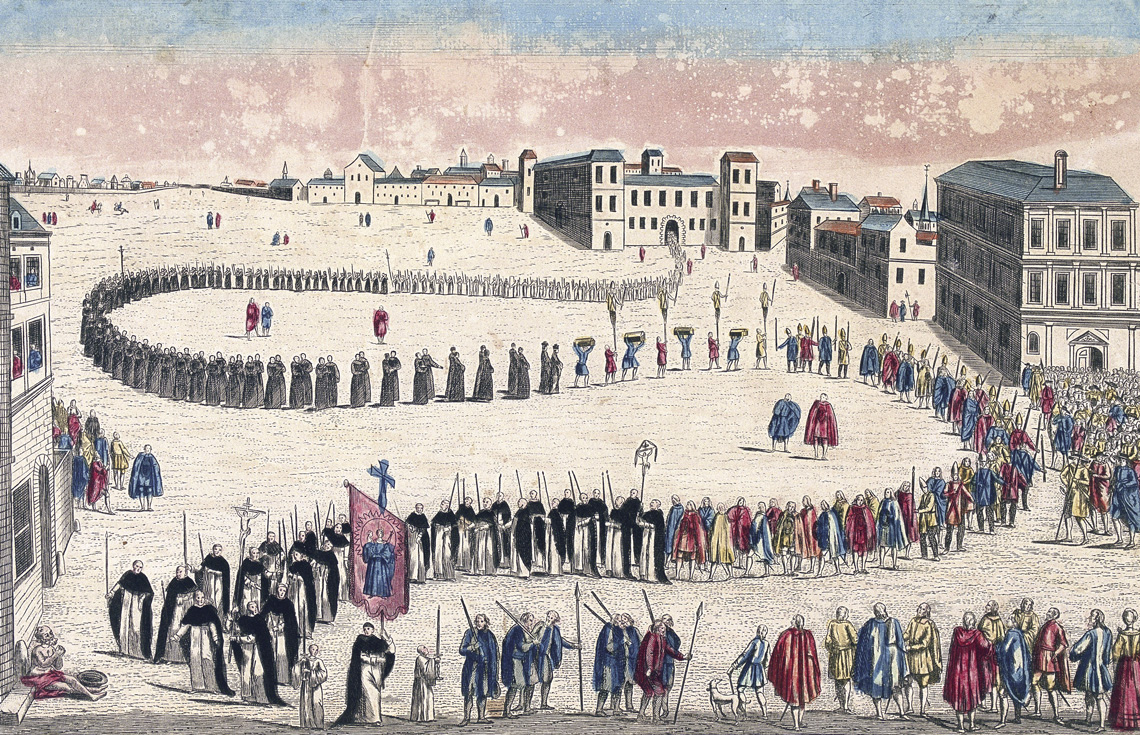

Universal History Archive / UIG / FotoarenaGrand procession of the auto-da-fe of criminals sentenced by the Inquisition at Lisbon, an 18th century engravingUniversal History Archive / UIG / Fotoarena

Two documents highlighted in the book, dated 1760 and 1772, focus on Ângela Maria Gomes, a freedwoman who worked as a baker in what is now the city of Itabirito. She was denounced as “the greatest sorceress of the village” because she practiced both vodum and Catholicism. The tribunal never formally prosecuted her, but people like her endured persecution, imprisonment, and the destruction of their shrines and ritual objects. “This shows why we cannot measure the impact of inquisitorial religious violence solely by the number of trials and sentences,” the authors write.

Another recent contribution on this subject is the book As feiticeiras do Império português – Gênero, relações de poder e Inquisição (1541–1595) (The witches of the Portuguese Empire: Gender, power relations, and the Inquisition [1541–1595]), by historian Marcus Vinícius Reis. Just released by Paco Editorial, the book is based on his 2018 doctoral dissertation at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG). Reis examines sixteenth-century trials of women accused of witchcraft. “Most of these women weren’t trying to break with the Catholic Church or with God,” he explains. “Practicing witchcraft was often a strategy for social and financial survival.” Now a professor at the Federal University of Southern and Southeastern Pará (UNIFESSPA), Reis notes that the women were frequently betrayed by their own clients.

“Worried they might be denounced by others, some clients preemptively denounced the witch. By confessing their own ‘sins,’ they hoped for lighter sentences—or even absolution,” he says. “At the same time, many of these women were targeted simply for living their sexuality openly: they refused to marry and had multiple partners.”

For Assis of UFV, such episodes reveal how the Inquisition frayed the fabric of community life in colonial Brazil. A case in point is the very first denunciation recorded during the second visitation to Bahia, on September 11, 1618, when Melchior de Bragança, a Jewish physician who had converted to Catholicism, denounced fellow New Christians. “Old Christians and converted Jews coexisted peacefully until the Inquisition arrived and actively encouraged such denunciations,” Vainfas concludes.

In the second visitation, the most frequent accusations were the practice of Judaism (87 cases), followed by sodomy (30), heresy (21), dealings with the devil (18), and blasphemy (7). Even though the rediscovered dossier multiplied the known cases nearly fivefold, the total still fell short of the first visitation, carried out about 20 years earlier, which logged roughly 900 denunciations.

“While New Christians are often assumed to have been the main target of the Inquisition, that was not the case during the first visitation,” notes Fernandes of UnB. Of the 240 trials that came out of those denunciations, only 17 dealt with Jewish practices. “So while Judaism topped the list of accusations, this wasn’t reflected in prosecutions. If the goal was to persecute New Christians, in practice it was Old Christians who were tried in greater numbers,” he explains.

Fernandes explores this further in his book A defesa dos réus – Processos judiciais e práticas de justiça da primeira visitação do Santo Ofício ao Brasil (1591-1595) (The defense of the accused: Judicial proceedings in the first visitation of the Holy Office to Brazil [1591–1595]), published in 2022 by Fino Traço. Based on his 2020 doctoral dissertation at UnB, the study shows that the largest share of cases involved heretical propositions (68), followed by blasphemy (29), sodomy (24), and so-called “gentile” practices, such as pagan festivals and Indigenous and African rituals (18).

About 28% of defendants, he finds, received only light penalties—prayers, fines, or no conviction at all. Many were acquitted for lack of evidence, what the tribunal termed “defects of proof.” One such “defect” was proof of personal enmity between accuser and accused. “Confession also weighed heavily: admitting to the charges could lead to acquittal or reduced sentences,” Fernandes explains. “Before hearings began, inquisitors would declare a ‘period of grace’ during which people could voluntarily confess their sins.”

The second visitation, in contrast, produced only nine trials—far fewer than the 240 of the first. Assis and Vainfas offer a potential explanation: the second visitation may not have been solely about punishing heresies or crypto-Judaism. Instead, it also seems to have sought intelligence on the ties between Brazil’s New Christians and those who had resettled in the Netherlands, which had become a refuge for Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal.

“The second visitation unfolded during the Iberian Union, when the Portuguese and Spanish crowns were joined under the Philippine dynasty. At the time, Spain was at war with the Netherlands, and there were suspicions that the Dutch were planning an invasion of Brazil,” Assis explains. “Those fears proved justified: the Dutch invaded Bahia in 1624 and Pernambuco in 1630. In that sense, the Inquisition’s anxieties about Dutch designs on Brazil’s sugar-rich Northeast were not unfounded.”

The story above was published with the title “Bahia of all sins” in issue 354 of August/2025.

Books

ASSIS, A. A. F. de & VAINFAS, R. (ed.). Segunda visitação da Inquisição à Bahia (1618-1620): Denúncias completas e inéditas com ortografia atualizada. São Paulo: Cosac, 2025.

FERNANDES, A. N. A defesa dos réus: Processos judiciais e práticas de justiça da Primeira Visitação do Santo Ofício ao Brasil (1591-1595). Belo Horizonte: Fino Traço, 2022.

MAIA, M. & RODRIGUES, A. (ed.). Sacerdotisas voduns e rainhas do rosário: Mulheres africanas e Inquisição em Minas Gerais (século XVIII). São Paulo: Chão Editora, 2023.

REIS, M. V. As feiticeiras do Império português: Gênero, relações de poder e Inquisição (1541-1595). São Paulo: Paco Editorial, 2025.