In approximately 427 BCE the Greek playwright Sophocles (496–406 BCE) wrote Oedipus the King, a play about the ruler of a city ravaged by plague, a tragedy resulting from a curse of the gods. Reflecting on the fear of death millennia later, Turkish writer Orhan Pamuk, winner of the 2006 Nobel Prize for Literature, is writing a novel that unfolds in 1901 during an outbreak of bubonic plague in Asia. From Ancient Greece to the contemporary period, through the Middle Ages and the post-war period, writers and artists have used the plague repertory to reflect on the human condition and criticize those holding the reins of political power and the existing social conditions. In Brazil, motivated by the novel coronavirus pandemic, researchers are initiating discussions on how these types of events can influence cultural production. At various institutions throughout the country, courses, public classes, and seminars on the topic have become part of the academic program for the second semester.

– Times of uncertainty

– Health professionals under emotional stress

– The puzzle of immunity

– The risk of traveling by plane

– Varying investment in science

– Sharing and expanding knowledge

Widely defined as a contagious disease or epidemic that causes large numbers of deaths, plague is a recurrent element in literary history and plays a central role in Sophocles. “Oedipus the King puts forward an image of the plague as the primary symptom that there is a breakdown in that society,” notes Francine Fernandes Weiss Ricieri, from the School of Philosophy, Language, and Human Sciences at the Federal University of São Paulo (EFLCH-UNIFESP). Ricieri, a literature historian who has been researching the relationship between Brazil, Portugal, and France in nineteenth-century poets for over 20 years, notes that in the literary universe the plague is often used as an allegory to address political and social issues. The Decameron, written in Italy by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313–1375) between 1348 and 1353, tells the stories of ten people who flee Florence to escape the black plague. “The work addresses a number of issues, including female eroticism and sexuality. While much of their society was dying, the elite were able to isolate themselves so as not to contract the disease. Under our present circumstances it seems obvious how much the issue of social inequality figures in the narrative,” she observes.

In Brazil, the COVID-19 pandemic has shown art historians that a distinct field dedicated to investigating plague’s influence on the artistic imagination is lacking. “Until today, the plague has been addressed from the point of view of iconography, through analyzing specific episodes or works. It has never been a central issue for art history curators and researchers. The reality brought about by the pandemic is beginning to change this scenario. We’re mobilizing to create projects that will allow us to investigate the subject in a systematic way,” says Ana Gonçalves Magalhães, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of São Paulo (MAC-USP).

Wikimedia commons

Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel painted The Triumph of Death in 1562, evoking a portrait of the plagues, epidemics, and conflicts that had stricken EuropeWikimedia commonsThe museum is preparing a retrospective of the works of artist Regina Silveira, a retired professor from the Art Department at the School of Communications and Arts (DAP-ECA) at USP. The exhibition will be inaugurated once the MAC is open to the public, on a date to be defined. During her career Silveira’s work has presented reflections on a catastrophic future. “Ever since 1996, when I installed the footprints of wild animals as a direct intervention in the lobby of the Museum of Contemporary Art in San Diego in the United States, my imagination has been taken over by these narratives that suggest sudden, phantasmagoric invasions of different architectures,” the artist explains. This same theme of uncontrollable invasions is also at the origin of many works in her Irruption series, she says, which show accumulations of human footprints in unusual situations. “At the same time, the images of giant, insect pests, which I filled a large glass pavilion with at the Banco do Brasil Cultural Center [CCBB] in Brasília, in 2007, were a perverse and stunning allegory of our political elite. Named Mundus admirabilis, the work launched others that more directly dialogued with historical and biblical plagues, seeking their corollaries in contemporary times, such as violence, corruption, and the deterioration of daily life.”

Thinking along similar lines as Magalhães at MAC-USP, Maria Berbara, from the Department of Art Theory and History at the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ), notes that the subject is not among the main areas of thought in the field of art and culture history. Based on research she has conducted since the 2000s on the artistic and cultural exchanges that took place between Europe and the Americas during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in recent months Berbara has begun to question the narratives adopted regarding the colonization of the Americas. The use of gunpowder, for example, has always been pointed to as a central reason for the speed with which settlers colonized the New World. “The devastating demographic impact of epidemics among native populations was seen as a secondary theory to explain this process. The current situation reminds us that, in reality, it must be seen as a primary cause,” observes the historian. Berbara believes that the lack of attention given to the fundamental role played by epidemics on the arts is possibly related to the fact that, throughout the twentieth century, researchers in art and culture history sought to build their own niche in research, which operated with autonomy as regards economic or social factors. “This search for independence from other fields of knowledge ended up causing us to overlook certain historical factors that deserve more attention, such as epidemics,” she says.

Angelo Agostini: The Carnevale of 1876. Revista Illustrada, nº. 10, March, 1876 / Reproduction

Illustration by Italian artist Angelo Agostini depicting yellow fever reaping lives during the Carnevale of 1876Angelo Agostini: The Carnevale of 1876. Revista Illustrada, nº. 10, March, 1876 / ReproductionIt is estimated that the black plague was responsible for the deaths of one-third of the world population between 1346 and 1353, which had consequences for the artistic imagination. “As a reflection of the disease, which was interpreted as divine punishment, paintings of devotion to the saints, especially those believed to protect people from the plague, increased dramatically,” says Tamara Quírico, from the Department of Art Theory and History at UERJ. For over 20 years Quirico has studied medieval Christian art from the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and the iconography related to the Last Judgement. Historian Juliana Schmitt, a researcher of the macabre aesthetic for more than a decade, explains that in medieval Christian Europe the prevailing idea held that death was the transition to a full spiritual life. Funeral rites sought to ensure an organized transition to this other plane, in addition to avoid showing the process of bodily decomposition. “The arrival of the black plague broke with this conception. The disease left marks on the body, and people died suddenly, sometimes in public places. Bodies might remain decomposing on the street for days, and funeral rituals were no longer performed,” she says. “The reassuring idea of death in the Christian conception was replaced by the idea of chaotic death caused by the plague,” observes the historian, who has just completed postdoctoral research at the Federal University of Juiz de Fora (UFJF).

According to Schmitt, everyday images related to the disease outbreak began to reappear in iconography and literature over the following years, fueling what is now known as macabre aesthetics. “What characterizes macabre works is the emphasis given to the processes of bodily decomposition,” the historian says, explaining that this aesthetic had already existed before, but was given impetus by the black plague. Thus, frescoes in cemeteries and churches, illuminated manuscripts, and poems began to deal with subjects like the worms that meander through decomposing bodies, and corpses that abandon their graves to encounter the living.

Wikimedia commons

Mal’aria, painted by French artist Ernest Hébert in 1848 and 1849, is in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay, in ParisWikimedia commonsIn the context of this imagery, says Quírico, the theme of the Danse Macabre began to stand out, especially in the frescoes and illuminations that have been preserved until today. In these images, corpses or skulls dance with the living, carrying objects related to death such as sickles and coffin lids, as well as musical instruments, adding an atmosphere of festivity. Analyzing the meanings these works held for people in the Middle Ages, Schmitt says that they represented the idea that death is universal, affects everyone regardless of social class, and can arrive suddenly. “The Danse Macabre can be considered an attempt to rework, through art, the chaos that was a feature of society at that time,” she says.

Schmitt also points out that throughout history the Danse Macabre has seen a variety of reinterpretations, including the engravings of Hans Holbein (1497–1543) and the verse of the romantic poets, who had an appreciation for the aesthetics of medieval culture. “At the end of the 18th century, the Romantic poets revived medieval themes to oppose the neoclassical ideal prevalent in the preceding decades, which had valued the search for beauty and harmony in art and poetry,” the historian observes. Years later, the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821–1867) also drew on this imagery, and even published a poem with the title “Dança macabra,” in The Flowers of Evil, in 1857. The 1959 film The Seventh Seal, by Swedish director Ingmar Bergman (1918–2007), tells the story of a knight who returns home after ten years fighting in the crusades and finds his village afflicted with the black plague. Bergman uses the image of Death leading away the protagonist and his friends—who, lined up in a row, hark back to the iconography of the Danse Macabre.

Wikimedia commons

The Triumph of Death at the Oratorio dei disciplini, in Clusone, Italy. Created by Giacomo Borlone de Buschis in the 15th century, it is one of the first works on the dance of deathWikimedia commonsEven before the current pandemic, the theme of the plague haunted the imaginations of contemporary writers. Addressing his creative process for writing a book on the theme, in an opinion article published in The New York Times in April Orhan Pamuk discusses several other authors who have published works based on the subject. The indifference of governing authorities, efforts to hide the true size of the problem, the spread of false information, and the idea of the plague as something brought on by an outsider are common elements in many of these works. Pamuk emphasizes that some writers, like British novelist Daniel Defoe (1660–1731) and the French-Algerian philosopher Albert Camus (1913–1960), went beyond political and social issues, using the image of plagues to deal with issues intrinsic to the human condition, such as the fear and dread caused by the proximity of death, and the feeling of strangeness brought on by the arrival of new diseases. Published in 1722, Defoe’s A Journal of the Plague Year, reports on daily life in London during the “great plague” that devastated the city from 1665 to 1666.

Daniel Bonomo, from the School of Languages at the Federal University of Minas Gerais (UFMG), believes that in both A Journal of the Plague Year and in Robinson Crusoé (1719), Defoe is exploring the effects of confinement. “The narrator describes the severe measures taken in London at the time. Houses that sheltered the sick were locked from the outside and identified with a red cross, with guards watching at all times so that nobody could enter or leave,” notes Bonomo, a participant in an online course that is discussing the issue of epidemics in the literary imagination. The lecture cycle at UFMG began in July and will continue through the end of the second semester of 2020.

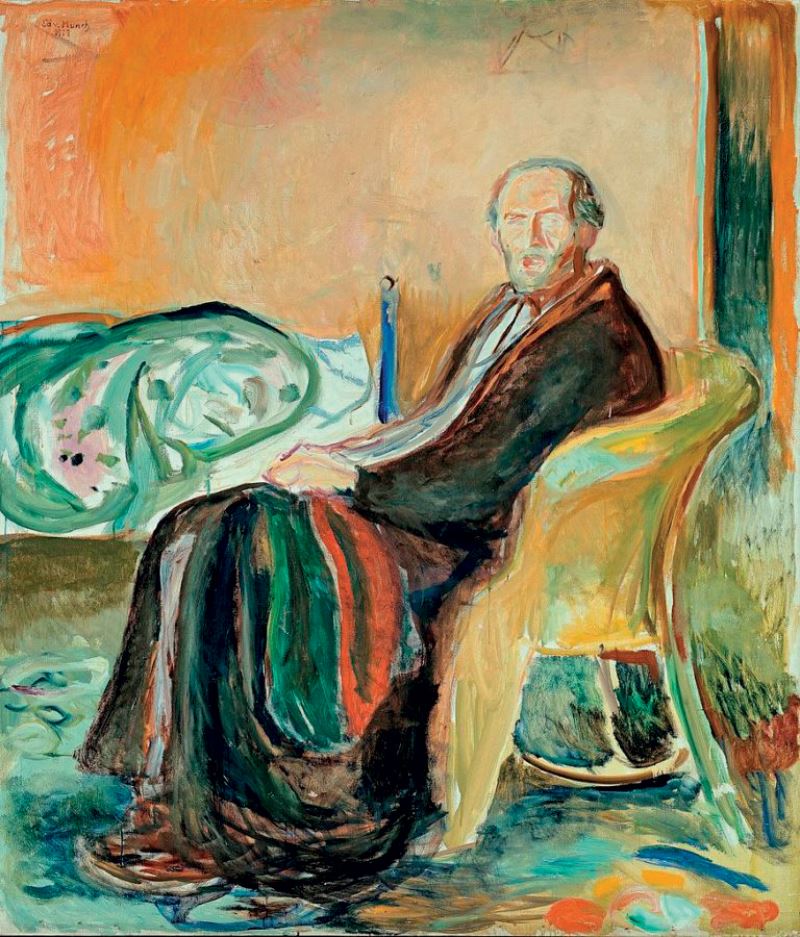

Nasjonalmuseet / Lathion, Jacques

Self-portrait painted by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch after contracting the Spanish flu virus in 1919Nasjonalmuseet / Lathion, JacquesAnother celebrated book on the subject is Camus’s The Plague. Published in 1947, the novel depicts an epidemic in the Algerian city of Oran and its effects on the local population. Researchers of Camus’s work note that The Plague was read at the time as an allegory of the Nazi occupation of Paris during World War II (1939–1945). Raphael Luiz de Araújo, who defended his doctorate on Camus at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Human Sciences (FFLCH) at USP in 2017, says Camus’ production can be divided into three cycles, the first of which involves works that address the absurd circumstances of human existence. The Stranger (1942) is part of this group, telling the story of a man in Algiers who, days after burying his mother, ends up murdering a young Arab. The second cycle, which includes The Plague, is marked by the idea of collective revolt as a positive response to feelings about the absurdity explored in the writer’s first cycle. “It’s about the search for an ethical reaction to our anguish in the face of the tragedy of human destiny,” says Araújo, who translated Camus’s first Notebooks for Brazilian readers. He believes the third cycle, which was not completed due to the writer’s premature death, would have addressed the theme of love.

Claudia Consuelo Amigo Pino, a professor of French language and literature at the Department of Modern Literature (DLM) at FFLCH-USP, notes that the Nazi occupation in France instituted an oppressive surveillance system, which generated distrust and gave vent to prejudices of every type. “At first, people thought it would be a temporary situation, and the lack of awareness regarding the seriousness of the problem made it become even worse, which is also the case in epidemics like the one we’re experiencing today,” she says. “In The Plague, Camus warns that catastrophes, such as epidemics or wars, can only be confronted through early awareness and working together.” In 2013, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, Pino organized an extension course that studied Camus’s career. Today, she is one of the coordinators of a program of public classes on epidemics being developed at FFLCH-USP, which will launch in September.

Reproduction

A still from Swedish auteur Ingmar Bergman’s film The Seventh Seal, a reinterpretation of the macabre iconography that gained impetus during the Middle AgesReproductionPhilosopher Leandson Vasconcelos Sampaio reflects that in Camus’s 1947 work, the plague can be understood “as a symbol of our fragility.” In fact, it is around this very idea of death that many of Camus’s works revolve, including The Stranger, The Rebel (1951) and The Myth of Sisyphus (1941). “To him, the awareness of the finite nature of human existence lights the way for people’s first contact with the absurd. In Camus’ book, the plague is a symbol for the reader to reflect on ethics and the need for people to engage in the face of collective catastrophes. Thus, by addressing death, the author writes in support of life,” Sampaio states.

The destruction of the human species is a frequent theme in fictional works that confront apocalyptic scenarios, in which epidemics end up assuming symbolic roles, among them the desire to reconstruct society from scratch. In a research project she’s been developing since 2018 concerning science fiction and cultural productions about the undead, or zombies, Valéria Sabrina Pereira, from the School of Languages at UFMG, lists different works in which this desire is evident. In Zone One (2011), for example, American writer Colson Whitehead describes a post-apocalyptic country, where survivors come together to fight the zombies that now dominate the cities. “Among them is the protagonist, a black man who begins to question if—when life returns to normal—society will continue to be marked by social inequalities and racism,” says Pereira. “Many works on zombies function as a satire of the idea of ‘new normal’ that develops after apocalyptic situations, showing society’s desperate attempts to return to its traditional model,” she explains. André Cabral de Almeida Cardoso, from the Department of Modern Foreign Languages at Fluminense Federal University (UFF) has, since 2016, been developing a research project on dystopias and contemporary apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic narratives. He observes that in some ways, these narratives about dystopias ended up anticipating the current crisis. “Today, now that we’re confronted by a scenario that until recently was only fictional, these works help us to deal with the feeling of perplexity and uncanniness that arises from this situation,” he concludes.

Project

Traces of Nemesis: The last essay by Albert Camus (no. 14/15584-0); Grant Mechanism Doctoral (PhD) Fellowships in Brazil; Principal Investigator Claudia Consuelo Amigo Pino (USP); Investment R$171,509.63.

Scientific article

BONOMO, D. R. Experimentum in insula: Robinson Crusoé nas origens do aborrecimento. Literatura e Sociedade. Vol. 22, no. 24. pp. 117–31. 2017.

Book

SCHMITT, J. O imaginário macabro na Idade Média – Romantismo. São Paulo: Alameda Editorial, 2017.