The way we live and die has been transformed by the novel coronavirus, and that could soon start taking a heavy toll on people’s mental health—if it is not doing so already. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), from its December 2019 discovery in China to July 27, 2020, the virus has infected over 16 million individuals, killed 646,000, and continues to spread. In an attempt to curb the spread of Sars-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, governments and health officials from different countries have imposed rules that change the way people live and relate to each other.

Without warning, most commerce, industries, schools, places of leisure, and physical activity centers have been closed, and people’s mobility has been restricted. Those who are able to self-isolate at home have done so, adapting to remote work and helping their children adapt to online education. Wearing masks in public areas has become commonplace and physical contact has been discouraged—kisses on the cheek and handshakes are a thing of the past. Those who need to leave their homes do so in constant fear of catching the virus, while those who become infected experience not only physical symptoms but also the fear of developing the severe form of the disease and needing hospitalization. In hospitals, COVID-19 patients are isolated from physical contact with family members while undergoing treatment, interacting solely with health professionals. Doctors and nurses, in turn, are constantly exhausted and distressed due to the high death toll and their increased risk of becoming infected and taking the virus home to their own families (see article). Even the process of dying has become lonelier, and those who lose someone to COVID-19 often have to say goodbye without full closure.

Despite the human capacity to adapt to change, facing so much adversity in such a short time can create an overload of stress that has been concerning international health authorities and mental health professionals alike. On May 13, the United Nations (UN) published a report pleading with governments around the world to take measures that reduce the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of the population. “The mental health and wellbeing of whole societies have been severely impacted by this crisis and are an urgent priority to be addressed,” says the document. “We are likely to see a lasting increase in the number and severity of mental health problems.”

– Health professionals under emotional stress

– The puzzle of immunity

– The risk of traveling by plane

– Varying investment in science

– Sharing and expanding knowledge

– Pandemics as allegory

The WHO considers mental health to be a neglected area, receiving an average of 2% of the health budget from countries, despite neurological and psychiatric diseases affecting nearly 1 billion people. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), mental disorders generate direct and indirect costs of US$2.5 trillion (4% of the world GDP). “Unless we act, a large percentage of people will be seriously affected, which will in turn impact the economy of these countries,” shared psychologist Dévora Kestel, director of the WHO Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse,with German TV station Deutsche Welle the day after the report was released.

Some experts have suggested that mental health problems could themselves turn into a new pandemic. For now, however, it is impossible to know how large the problem could become. “We have not had time to collect enough data to allow us to adequately answer this question,” said United States psychiatrist Carol S. North, a trauma and disaster specialist from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, in an e-mail to Pesquisa FAPESP. North believes the research developed during previous pandemics, such as the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) epidemic, is limited. “We need to wait for good data to show how COVID-19 is affecting people,” she adds.

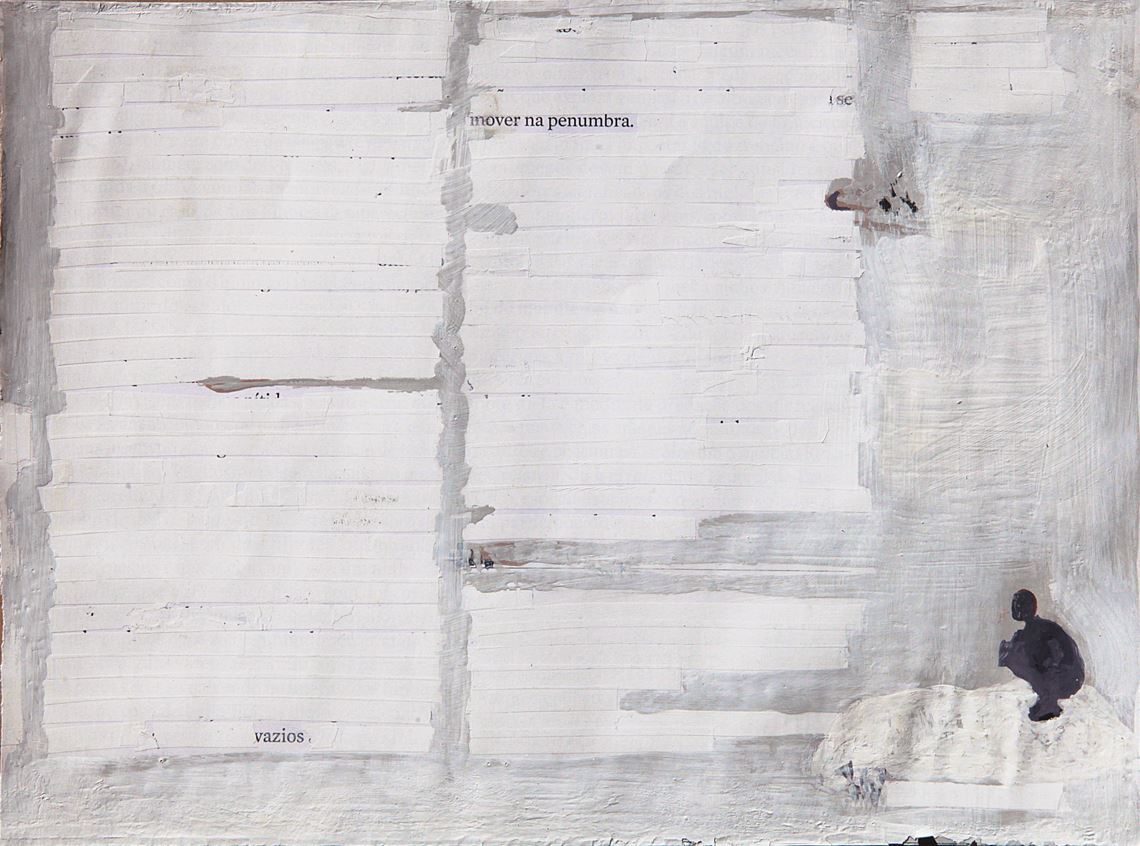

Despite the short time since the beginning of the pandemic, initial studies suggest that changes to our daily routine and the fear of catching the virus and becoming ill are exacerbating psychological distress—and possibly psychiatric problems—in some countries. The number of participants in these online surveys has been low. Their results, although far from definitive, give us an idea of what may lie ahead. It will take months or years to obtain more precise information—once researchers have been able to dive deeper into this topic.

In China, researchers from the Northwest Normal University used a messaging application with 1,074 people aged 14 to 68, asking questions that help identify signs of depression, anxiety, alcohol abuse, and decreased psychological wellbeing. Nearly two-thirds were residents of Hubei province, where the city of Wuhan is located—the birthplace of the ongoing pandemic. The results, published last April in the Asian Journal of Psychiatry, showed that twice as many individuals had signs of severe depression in Hubei (11.4%) compared to the other Chinese provinces (5.3%) that had been less affected by the new coronavirus and were used as a benchmark. Something similar was observed in terms of alcohol abuse and addiction; the numbers were, respectively, 11% and 6.8% for Hubei and 1.9% and 1% for the rest of China.

Aline Van LangendonckIn April, a group from the Sichuan University, also in China, reported the findings of another online survey in the journal Medical Science – Monitor. It included interviews with 1,593 adults from Hubei and four neighboring provinces conducted in February, at the height of the outbreak, weeks after the enforcement of more restrictive isolation measures. For those quarantined, the proportion of people with signs of anxiety and depression was 13% and 22%, respectively—twice as high as that observed among those who were able to continue living relatively normal lives (7% and 12%).

Aline Van LangendonckIn April, a group from the Sichuan University, also in China, reported the findings of another online survey in the journal Medical Science – Monitor. It included interviews with 1,593 adults from Hubei and four neighboring provinces conducted in February, at the height of the outbreak, weeks after the enforcement of more restrictive isolation measures. For those quarantined, the proportion of people with signs of anxiety and depression was 13% and 22%, respectively—twice as high as that observed among those who were able to continue living relatively normal lives (7% and 12%).

The emotional wellbeing of children and adolescents also seems to have been significantly affected by self-isolation and fear of contagion. With parental authorization, 1,784 children from two primary schools answered questions that assessed signs of depression and anxiety, levels of concern about contagion, and optimism during the pandemic. Almost one in four students reported signs that pointed to depression and one in five had signs of anxiety, rates at least 30% higher than those observed in previous studies involving Asian children of similar age, according to an article published in April in the journal Jama Pediatrics. Symptoms of depression were more severe in Wuhan children than in those from a nearby town, Huangshi, which was under quarantine for a shorter period. “Findings suggest that, much like traumatic experiences, serious infectious diseases can influence the mental health of children,” wrote the authors of the paper, coordinated by researcher Ranran Song, from Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

There is no reason to suspect that preliminary results from China differ significantly from those found in the West. Here, the disease has spread rapidly for months, but data about its effect on people’s mental health is scarce. In a survey involving 1,143 Spanish and Italian parents of children and adolescents, conducted by psychologist Mireia Orgilés, from Miguel Hernández University in Spain, 86% of parents reported that their children experienced emotional and behavioral changes during quarantine. According to an article posted in April in the PsyArXiv repository, 77% of children and adolescents faced difficulties concentrating, 52% became bored more easily, and 39% became more irritable and restless.

In Brazil, psychiatrist Guilherme Polanczyk and his team at the Department of Psychiatry of the University of São Paulo School of Medicine (FM-USP) began surveying children and adolescents aged 5 to 17 from all over the country in June, also using online questionnaires. The researchers intend to assess changes in their routine, behavior, and emotions over the course of a year. Preliminary data from the analysis of 4,504 responses indicate that children have been spending a lot of time online (half of them use electronic devices for more than eight hours a day, not counting classes), sleeping less, and becoming more sedentary (43% of them had not exercised for two weeks). They also suggest that 13% of the participants had some level of anxiety and 16% had signs of depression that warrant being examined by a doctor. “Those are high rates, even higher in children of parents who are stressed and of lower socioeconomic status,” states Polanczyk.

Aline Van LangendonckThe numbers in these surveys are impactful, but they should be considered with caution. Despite the efforts of the researchers, online surveys do not always cover a representative sample of a population. For example: wealthy and educated populations are more likely to have Internet access, and therefore more likely to respond to the survey than those on the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum. People with some degree of psychological distress are also more likely to take the time to answer such questions than those who feel well.

Aline Van LangendonckThe numbers in these surveys are impactful, but they should be considered with caution. Despite the efforts of the researchers, online surveys do not always cover a representative sample of a population. For example: wealthy and educated populations are more likely to have Internet access, and therefore more likely to respond to the survey than those on the other end of the socioeconomic spectrum. People with some degree of psychological distress are also more likely to take the time to answer such questions than those who feel well.

In addition to these limitations, there is a significant difference between psychological distress and psychiatric disorders, which these surveys do not always make clear. Both relate to feelings and emotions that may or may not arise in response to environmental changes and cause emotional distress, affecting one’s ability to perform daily activities. “What distinguishes one from the other is their intensity,” explains psychologist Christian Kristensen, from the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul (PUC-RS). “At a certain point, the degree and duration of distress or impaired function makes the issue pathological and can constitute a psychiatric disorder,” adds the researcher, who is part of a PUC-RS group that is conducting another online survey to assess the effect of the pandemic on the mental health of Brazilians. In addition to being less intense, psychological distress does not last as long (usually days) and rarely requires medication, but it is two to three times more frequent than psychiatric disorders.

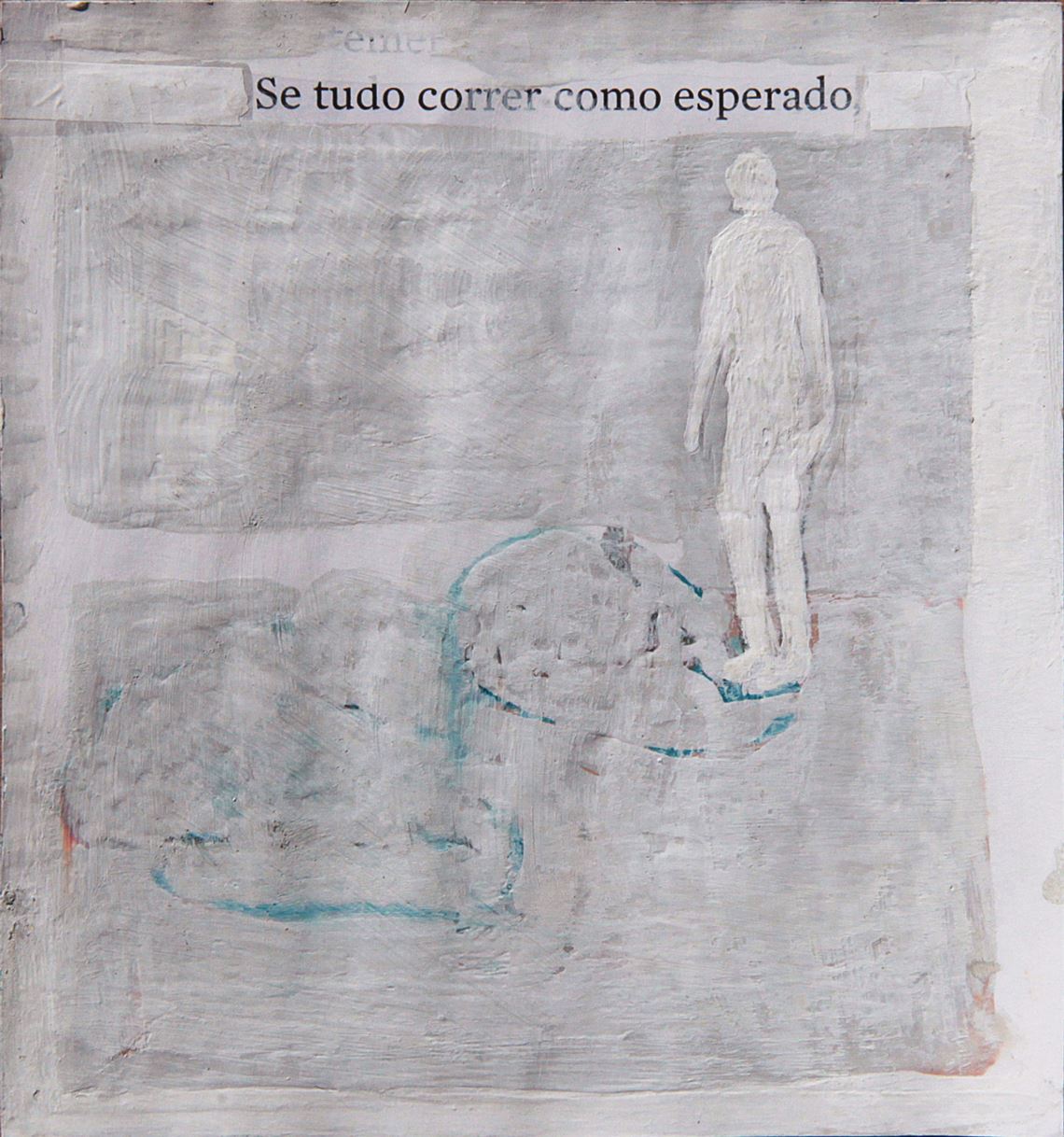

Another reason to carefully analyze the numbers is that many people, even those exposed to traumatic events, do not develop psychiatric disorders. While studying disasters, Carol North found that less than half the people who faced intense trauma developed a psychiatric issue. “Rates are much lower in the general population,” claims the psychiatrist. “People are resilient.” However, North suspects that most people, including those not exposed to the virus, may experience some degree of psychological distress due to fear of infection, self-isolation, and financial losses.

“The emergence of mental disorders depends on the individual’s biological vulnerability and environmental factors. Faced with such a significant environmental factor as this pandemic, even the least vulnerable people can develop issues,” explains psychiatrist Luis Rohde, from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS). “Among those not in this group, the majority will experience a temporary period of stress and anxiety,” adds Polanczyk, from USP.

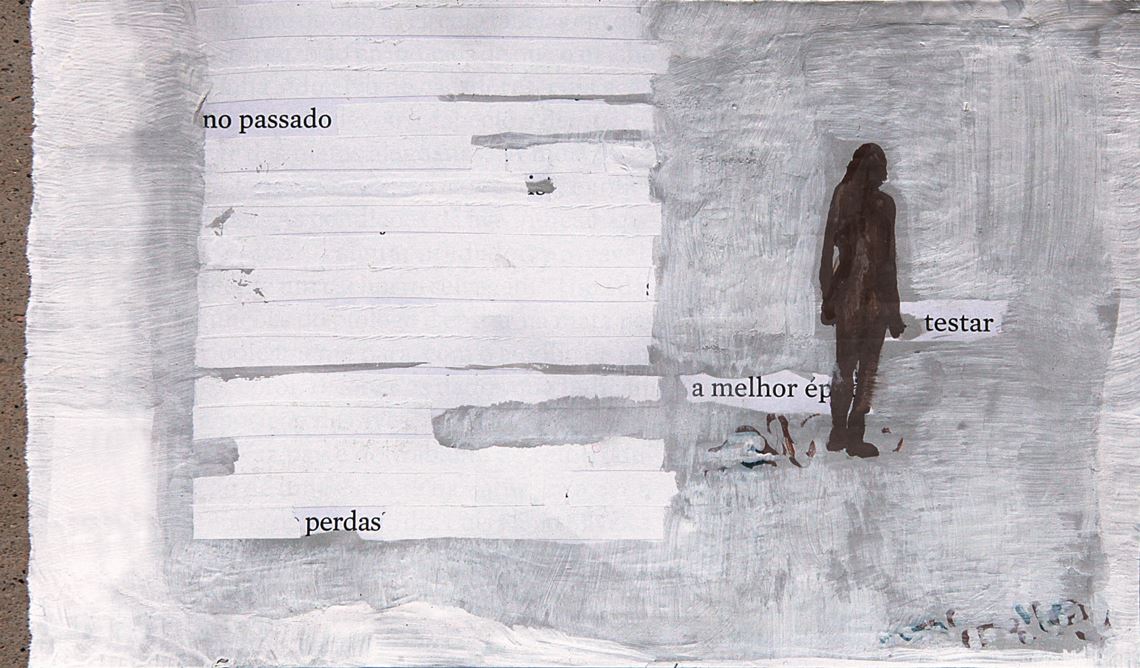

Aline Van LangendonckIn addition to anxiety and depression, experts also expect an increase in post-traumatic stress disorder, which consists of reliving highly stressful and life-threatening events, and prolonged mourning—when one has a hard time overcoming the loss of loved ones. “The pandemic has already caused a collective mourning process in the population over the loss of life as we knew it, and it will likely aggravate the mourning process of those who lose loved ones to COVID-19,” states psychologist Maria Júlia Kovács, from the USP Institute of Psychology.

Aline Van LangendonckIn addition to anxiety and depression, experts also expect an increase in post-traumatic stress disorder, which consists of reliving highly stressful and life-threatening events, and prolonged mourning—when one has a hard time overcoming the loss of loved ones. “The pandemic has already caused a collective mourning process in the population over the loss of life as we knew it, and it will likely aggravate the mourning process of those who lose loved ones to COVID-19,” states psychologist Maria Júlia Kovács, from the USP Institute of Psychology.

Even a modest increase in cases of psychiatric disorders could overload a healthcare system that is unprepared to handle the problem. “The Brazilian healthcare system was established to treat more serious cases, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,” points out psychiatrist Jair Mari, from the Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP). “Patients with depression, anxiety, panic disorders, or drug problems remain in limbo.” Studies developed by Mari have indicated in the past that Brazil has proportionally few psychiatrists (3.2 for every 100,000 inhabitants; in rich countries, the ratio is 20 times higher), and that 85% of patients diagnosed with a mental health disorder do not undergo drug treatments that could help control the problem.

For Polanczyk, the pandemic could exacerbate social inequalities also in terms of access to mental health services. “Those most affected are likely to be poor children and adults, who are not even detected in online surveys,” he says. “In our study, we found that the number of children and adults with clinical symptoms is two to three times higher among those of low socioeconomic status than among the wealthy. The government must act to improve their situation.”

While the end of the pandemic remains elusive, psychiatrists and psychologists have some advice to help alleviate psychological distress: keeping a routine that is similar to that followed before the pandemic; going to bed and waking up at regular times; exercising; not increasing the use of alcoholic beverages; trying to develop hobbies and enjoying leisure activities; and not constantly following the news.

“These are general tips without any side effects,” claims psychiatrist André Brunoni, from FM-USP. Using online tools, Brunoni is currently assessing the effects of the pandemic on a sample of 4,000 people participating in the Longitudinal Study on Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil), which has been monitoring the health of 15,000 Brazilian civil servants for years. “We hope to be able to identify factors that increase the risk of mental disorders,” he explains.

Research participants with high stress levels will be referred to one of two long-distance care strategies to help deal with issues such as stress, insomnia, and negative thoughts: remote group therapy, consisting of five sessions with a psychologist for six to eight people, or psychoeducation, in which the participant receives textual and video material on techniques to deal with their symptoms. “If psychoeducation becomes as effective as teletherapy, it can help increase the number of people we can help,” adds Brunoni.

For the rest of the population, last June the USP psychiatry team launched a mobile application—COMVC, available for Android and iOS—that uses surveys approved by psychiatric entities to monitor anxiety, depression, insomnia, and burnout symptoms. Those considered to have moderate symptoms are given videos on how to deal with the problem. For severe cases, the app provides a list of institutions that offer free or low-cost emergency psychological care. “There are many mental health apps out there, but it can be hard to find quality information and treatment,” says psychologist Daniel Fatori, who coordinated the development of COMVC and is a postdoctoral intern at the institution. “We hope the app can help with mild to moderate cases.”

Projects

1. The Coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic’s impact on the mental health of participants of the longitudinal health study of adults (Elsa-Brasil) in the state of São Paulo (no. 20/05441-9); Grant Mechanism Regular Research Grant; Principal Investigator Isabela Judith Martins Benseñor (USP); Investment R$131,191.76.

2. Early childhood interventions and cognitive, social, and emotional development trajectories (no. 16/22455-8); Grant Mechanism Thematic Project; Principal Investigator Guilherme Vanoni Polanczyk (USP); Investment R$2,509,395.96.