In addition to fighting off internal revolts and foreign invasions, founding villages, and expanding the population into the country’s interior, the viceroys who ruled Brazil between 1640 and 1808 created institutions and promoted geographic, mineralogical, and botanical surveys to facilitate management of the territory and earn more wealth for the Portuguese government. The fourth viceroy, Vasco Meneses (1673–1741), sponsored the colony’s first literary society, the Academia Brasílica dos Esquecidos (Brazilian Academy of the Forgotten), which operated for a year between 1724 and 1725. The twelfth, Luís de Vasconcelos e Sousa (1742–1809), created the Natural History Office of Brazil, better known as the House of Birds, in the center of the city of Rio de Janeiro in 1784, which gathered Brazilian animals for display or to send to the Royal Museum of Ajuda and rural properties in Portugal. The institution was the embryo of the Brazilian National Museum, which was formally established in 1818 as the Royal Museum.

On arrival in Brazil in 1808, the Portuguese Court brought with it scientific and cultural institutions that stimulated knowledge of the territory and circulation of information through newspapers that were beginning to be printed in Rio de Janeiro. “Creating scientific institutions was part of Dom João VI’s strategy to transform the city of Rio into the seat of the Court,” highlights science historian Maria Amélia Mascarenhas Dantes, a retired professor at the School of Philosophy, Languages and Literature, and Humanities at the University of São Paulo (FFLCH-USP).

Íris Kantor, a historian from FFLCH, notes that the latest research validates the pioneering studies of historian Maria Odila Leite Silva Dias, a retired professor at USP. In one study, published in Revista IHGB (published by the Brazilian Historic and Geographic Institute) in 1968, Dias comments: “The role of state policy in this scholarly movement, mostly dedicated to natural sciences, deserves particular acknowledgement due to its multiple implications, both in guiding studies and in the mentality of the politicians involved in the independence process.”

In the study, she observes the pragmatism of the Portuguese government in promoting botanical and mineral surveys—encouraged since the late eighteenth century by the Portuguese statesman and Marquis of Pombal, Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo (1699–1782), with the objective of finding products of commercial value. “Science of this kind was standard practice for European countries in the Age of Enlightenment,” reiterates Silvia Figueirôa, a geologist from the School of Education at the University of Campinas (FE-UNICAMP), referencing the cultural movement led by France in the eighteenth century.

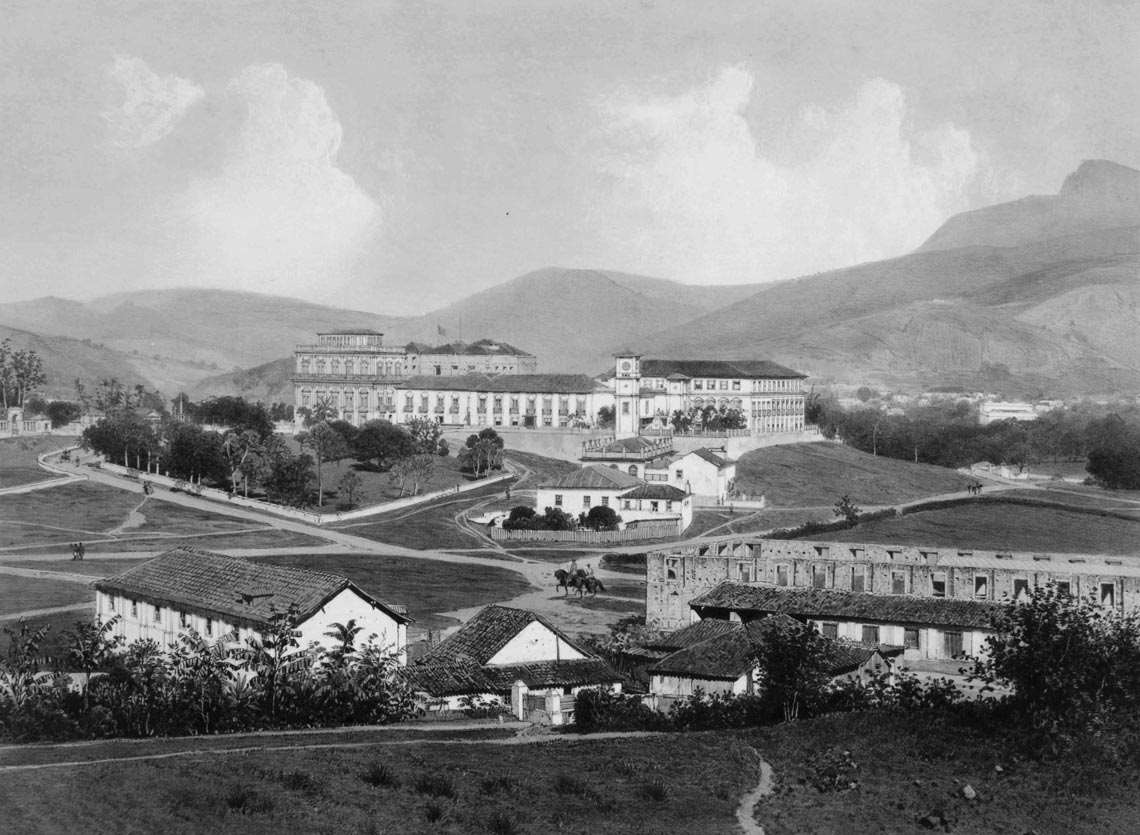

In 1818, the Portuguese Court created the Royal Museum with the aim of “propagating the knowledge and study of the natural sciences in the Kingdom of Brazil, in which are to be found thousands of objects worthy of observation and examination and which may be useful to commerce, industry, and the arts,” according to the decree issued upon its inauguration.

Brazilian National LibraryThe Botanical Garden of Rio de Janeiro in an 1856 drawing by Pieter Godfred BertichemBrazilian National Library

The power of maps

“Science, especially cartography, was part of the Portuguese Empire’s survival strategy in terms of strong inter-imperial competition,” says Kantor, one of the curators of an exhibition of old maps at the Naval Museum in Rio de Janeiro (see article). “The maps helped develop the imagined idea of Brazil and the notion of a cohesive and integrated territory. They were also used for population management, by indicating places where goods could be taxed.”

According to Kantor, Portugal supported scientific activities and institutions to “create a positive image of colonization, assuaging accusations of violence against indigenous people made by other European nations, and to demonstrate its control over the territory.” This is true of the New Lusitania map, completed in 1798 by the astronomer and frigate captain Antonio Pires da Silva Pontes Leme (1750–1805).

Adopting the island of El Hierro in the Canaries as longitude 0 (the Greenwich meridian was only recognized as international standard in 1884), the map details the networks of rivers, islands, mountains, settlements, indigenous villages, forts, land routes, and gold mines in Brazil. Together with historian Beatriz Bueno of USP’s School of Architecture and Urbanism (FAU), she located documents indicating that Portuguese diplomats presented New Lusitania to peers in London with the intent of demonstrating Portugal’s sovereignty and scaring away anybody interested in exploiting the riches of Brazil.

Lorelai Kury, a historian from the Oswaldo Cruz House at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation (COC-FIOCRUZ) in Rio de Janeiro, points out that unlike his wife Empress Leopoldina (1797–1826), Dom Pedro I (1798–1834) had little interest in science, although he still recognized its value. According to Kury, this was one of the reasons why in 1831, he chose José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva (1763–1838)—a statesman, naturalist, and mineralogist—to tutor his son, the future emperor Dom Pedro II (1825–1891).

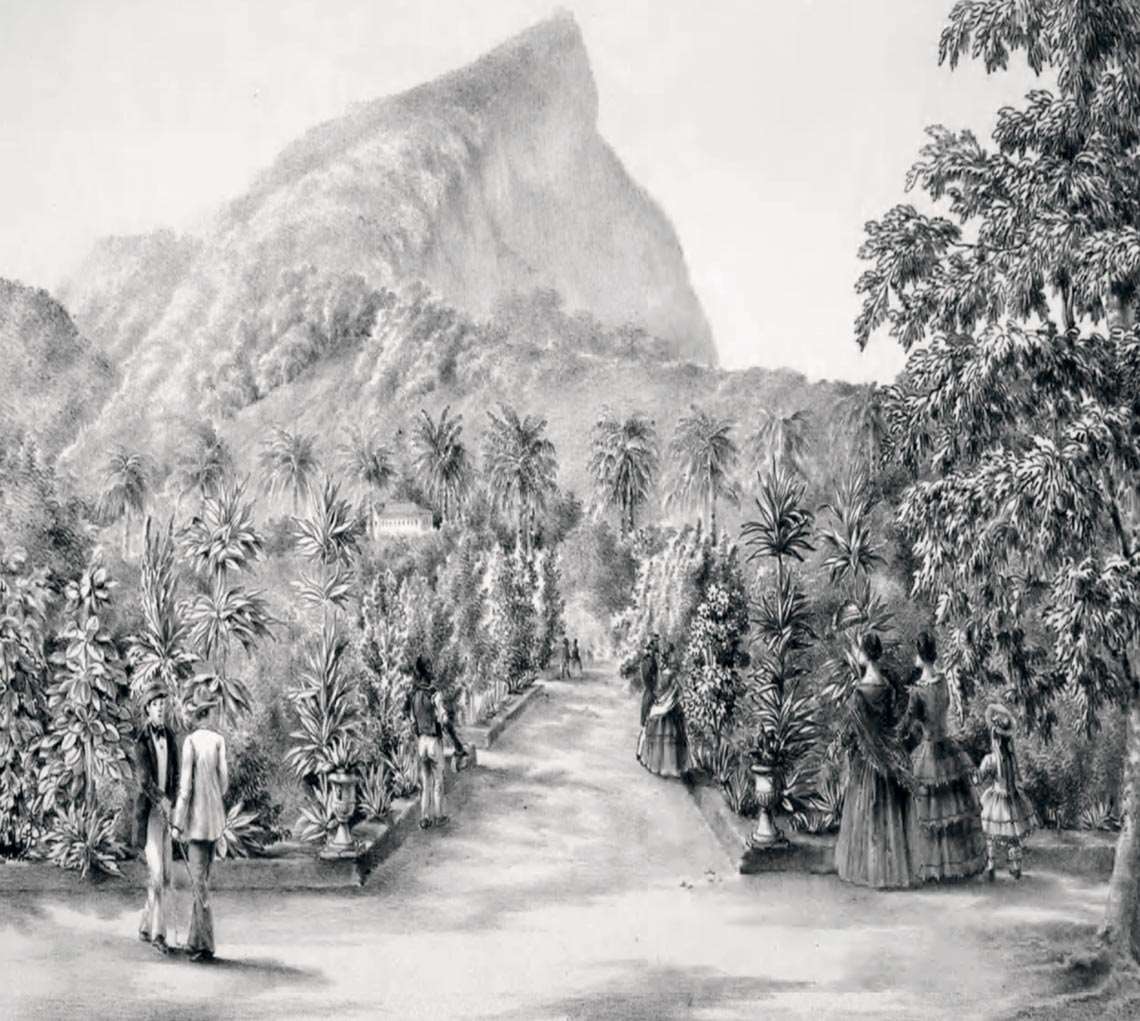

Brazilian National LibraryThe first building of the National Library, on Rua do Carmo, Rio de JaneiroBrazilian National Library

Self-taught scientists

“Until the second half of the nineteenth century, when they began to position themselves as producers of science, these institutions had little influence compared to the individuals who produced scientific knowledge,” stresses Kury. There were two groups of scientists: a few professionals employed by the government or institutions, and the amateurs, usually self-taught, who had to earn a living from another profession or did not need to work. “It was like that in other countries as well,” notes Figueirôa. “The chemist Antoine Lavoisier [1743–1794] was executed by guillotine because he was a tax collector under the Old Regime.”

Officials of the Portuguese Crown in Brazil, for example, included three German geologists: Wilhelm Ludwig von Eschwege (1777–1855), Wilhelm Christian Gotthelf von Feldner (1772–1822), and Friedrich Ludwig Wilhelm Varnhagen (1782–1842). The trio worked as mine inspectors and carried out mineralogical surveys in the country for more than a decade, until 1821 (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 317).

Among the amateurs were many religious people. In 1783, José Mariano da Conceição Veloso (1742–1811), better known as Friar Veloso, led an expedition into the forest near Rio de Janeiro that lasted four years and resulted in the book Flora fluminensis, published posthumously in 11 volumes from 1825 to 1831, describing 1,626 plant species grouped into 396 genera (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nºs. 172 and 289). Between 1824 and 1829, Leandro do Santíssimo Sacramento (1778–1829), a Carmelite friar and botanist from Pernambuco who studied philosophy at the University of Coimbra in Portugal, was director of Rio de Janeiro’s Botanical Garden, the second in Brazil, created in 1808—the first was in Belém, Pará, instituted in 1796 by royal decree from Queen Maria I (1734–1816). Both botanical gardens served the purpose of acclimatizing exotic plant species for cultivation in Brazil, or native species for commercial production.

Falling somewhere in between—self-taught but paid for his work—was a taxidermist called Francisco Xavier Cardoso Caldeira (?–1810) who ran the House of Birds for 20 years. In an article published in the journal Filosofia e História da Biologia in 2018, three researchers from Rio de Janeiro State University (UERJ)—Bruno Absolon, Francisco Figueiredo, and Valéria Gallo—reported that Caldeira slept at the museum and had three servants, two assistants, and two hunters, who added to the collection by shooting birds at a lake in front of the institution which he then stuffed. The museum closed in 1813 and what survived of the collection, which stood at almost 1,000 animals, remained in the country’s armory until 1818, when it was transferred to the newly founded Royal Museum (see Pesquisa FAPESP issue nº 272).

The Portuguese government asked specialists to look for places to mine saltpeter, a mineral used to make gunpowder, as well as plants with commercial value. One was José Vieira Couto (1752–1827), who had a degree in mathematics from Coimbra and was hired by the crown to identify mineral sources that could be exploited, as described in an article published by Dantes in the journal Science and Culture in 2005.

The first native doctors

Based in Rio, the Portuguese Court also tried to increase the number of medical specialists, previously only trained in Europe, by establishing the Bahia School of Surgery in Salvador and the Anatomical, Surgical, and Medical School of Rio de Janeiro, both in 1808 (see timeline). It thus established medical practice in Brazil, hitherto provided by barbers, bleeders, practitioners, and healers, noted COC-FIOCRUZ historian Flávio Coelho Edler in a 2009 article in the journal Acervo. At that time, there was still competition between specialists: doctors whose training was supported by the government had to compete for clients with healers who offered protection against virtually any disease. “Most people preferred healers because they made more sense in their world,” he says. In 1832, a decree transformed the medical schools in Rio de Janeiro and Bahia, removing the surgery course and allowing students to graduate in one of three areas—medicine, pharmacy, or childbirth—in line with the French model for medical education.